“My first sense of it came when I used to watch Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?,” says Raja’a Khalid, a Dubai-based visual artist.

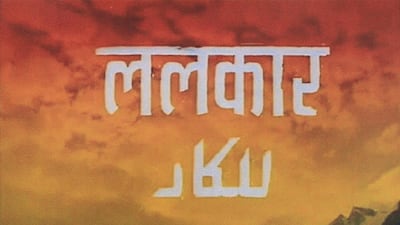

“It” is the disappearance of Urdu from contemporary Indian pop culture that inspired Khalid’s examination of the interaction of Urdu and Hindi script in Bollywood movie titles for her master of fine arts degree, which was awarded to her by Cornell University last year.

Right-to-left Urdu and left-to-right Hindi scripts “speak to one another”.

“The fact that one is written left to right and one is written right to left brings them in conversation with one another,” said Khalid, a Pakistani citizen raised in Dubai on a steady diet of English and Hindi pop culture. “The way Bollywood works is you have sort of this Rosetta Stone where the title would appear in English, Hindi and Urdu.”

By the late 1990s, the Urdu script was dropped. These days, Hindi stands alone.

What Khalid calls the “disappearing act” of Urdu from Bollywood titles is indicative of the growing distinction between Hindi and Urdu in media. The languages were mutually intelligible in media until recently.

Bollywood, with its history of Urdu poets turned screenwriters, retains Urdu words of Arabic and Persian origin alongside English.

Television, however, has shifted in the last five years to Shuddha Hindi, a dialect that favours Sanskrit nouns over those of English or Urdu origin.

Take Amitabh Bachchan. When the Bollywood titan first hosted India’s Kaun Banega Crorepati (Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?), he spoke a standardised Hindi with a good dose of English that was gradually replaced by Sanskrit terms.

On the legal drama Adaalat (The Courtroom), the lead actor has incorporated so much Sanskrit into his dialogue that Hindi speakers struggle to keep up. “He speaks in such indecipherable Shuddha Hindi that even the characters on the show don’t seem to understand,” says Khalid.

“Initially, when I saw it I thought it might be a self-parody.”

The distinction between Hindi and Urdu is a byproduct of national politics, a dichotomy first debated in 19th-century British-controlled India.

Hindi is closer to Urdu than Sanskrit. The sibling languages have grammar and syntax rooted in Khari Boli, a western Indian language unrelated to Sanskrit. Favoured from the 18th to the early 20th century, it was widely spoken and understood by Hindus and Muslims, who penned literature in both Nastaliq and the Devanagari script used for Sanskrit since the 19th century.

This language and a Perso-Arabic Nastaliq script became the official court language in 1837, favoured by three high-status Hindu castes who used it to gain employment in the British government.

“This is perceived by other Hindu castes as problematic in gaining employment so they push to get the Nagari script recognised at the same time,” says Khalid.

The Hindu revivalist movement uses Sanskrit-derived loan words and a Devanagari script. This incarnation, now defined as Hindi, became the official language of British India in 1900.

Mahatma Gandhi, the leader of Indian independence, wrote in Hindi and Urdu and called both by the same name, Hindustani.

“Gandhi, sensing this immense conflict between these two languages, had offered a two-script solution that both be recognised,” says Khalid.

“Even where we are living right now a lot of local Emiratis will speak to you in Hindi-Urdu and that’s the beauty of this. Someone might come from Peshawar, someone might come from some random village in India and they might be able to understand each other.”

• Khalid’s research is part of her continuing A Minor Histories Archive. Her work is at minorhistories.org.

azacharias@thenational.ae