The zigzagging patterns of rural Moroccan art brim over the frame in Fatna Gbouri's canvases; Vera Tamari depicts daily life in Palestine using ceramics, with her figures, women with clay jugs, seemingly stepping out from the reliefs; Mounirah Mosly embeds Saudi textile fragments into paint and works with palm-tree fibre.

For years, such work was dismissed by many institutional settings, treated as secondary to painting and sculpture. But the way female Arab artists embraced craft, particularly in the third quarter of the 20th century, was sharply reflective of the geopolitics of the time.

The region was emerging from colonial rule, and embracing handicrafts and artistic traditions was a means of asserting cultural identity. Ultimately, these artists helped cement modernism on local terms. They unravelled traditional boundaries of what can and should be considered art.

Horizon in their Hands, Barjeel Art Foundation’s first exhibition in Saudi Arabia, showcases these contributions in collaboration with King Abdulaziz Centre for World Culture – Ithra. Taking place in the centre’s museum, the exhibition brings together 50 artists from across the Arab world whose work from the 1960s to 1980s helped shape the region’s visual and cultural narratives.

Paintings by Safeya Binzagr document Saudi traditions, Emirati artist Najat Makki deftly incorporates henna into abstract compositions, textiles by Safia Farhat draw on Tunisian heritage, and batik silks by Saudi's Mona Al Munajjed explore the intersection between art and craft. The works together show how mediums dubbed as decorative and relegated to craft helped propel Arab modernism.

“This exhibition represents a shared commitment to recover and amplify narratives that have often been overlooked in modern art history,” Suheyla Takesh, director of Barjeel Art Foundation, said during her speech at the exhibition’s opening on Thursday. “At the heart of this endeavour is a celebration of the women artists from the Arab world. Their contributions between the 1960s and the 1980s continued to shape the contours of modernism, but sadly, too often they remain underrepresented in the stories we tell about art.”

Curated by Remi Homs, the exhibition grew out of Barjeel Art Foundation’s ongoing drive to increase the representation of female artists in its collection.

“It started after our show in the US called Taking Shape, focusing on the development of abstraction from the Arab world,” Homs says. As the team was putting together a list of the artworks for the 2020 exhibition, they found there was an under-representation of women.

“This led to the process of taking more time to research and to find new names.”

That initiative reached a declarative high point earlier this year, with an exhibition at Sharjah’s Maraya Art Centre. Titled Nadia Saikali & Her Contemporaries, it exclusively presented works by women artists in the Arab world, showcasing the strides they made in abstract art in the 20th century. Beirut was a focal point of the exhibition, showing the role the city played as a hub for women artists from across the region.

Horizon in Their Hands highlights another commonality. “We wanted to show that there are so many connections to be made,” Homs says. “There are so many things to unpack. The easiest way to proceed would have been to have the top 50 women artists from the Barjeel connections, but we wanted something more academic.”

The role of craft became evident. Artists across the Arab world, particularly women, began utilising traditional techniques and handicrafts in novel ways. The results were varied and moulded by specific cultural, political and personal influences.

Sometimes, there were overlaps. The exhibition highlights these connections eloquently. Makki’s henna and acrylic Window (1987) is displayed beside Jumana El Husseini’s Marriage (1974), which also makes use of henna and subtly evokes the significance of the material in matrimonial celebrations. As Tamari depicted Palestinian women at work with her 1974 ceramic relief, Tunisian artist Fela Kefi-Leroux was also working with the material, such as in her glazed and tiled work Agriculture (1964).

Then there were those who were rethinking the possibility of crafts alongside emerging technologies. Saikali’s Geodesic Landscape (1972) was scoffed at when it was first exhibited, but the light sculpture, a convex work within which translucent panels glow with a polychrome vibrancy, is now considered as a visionary statement piece by the Lebanese artist. Egyptian-French author Joyce Mansour took another route, using discarded metal and mixed media to create forms reminiscent of human organs.

The diversity is present even within a specific genre. Tapestry works, for instance, include Farhat’s famous The Bride (1963), a woven work that depicts a Tunisian woman in traditional wedding attire. But there are also examples from Ramses Wissa Wassef Art Centre, an institution in Egypt dedicated to preserving tapestry-making, with works depicting flora and fauna such as Nadia Mohammed's Garden Plants (2021) and the wonderfully meta Reda Ahmed’s Wool Yarn Dyeing at the Centre (2004).

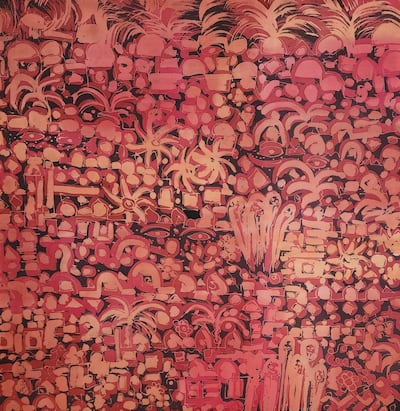

Al Munajjed’s silk works, meanwhile, take a wholly different approach, applying the ancient batik technique, where wax-resist dyeing is used to make intricate patterns, to depict the urban landscape of old Jeddah, with vibrant, kaleidoscopic patterns that leap from the silk.

“There is a great diversity to the techniques,” Homs says. “For me, I knew all the textiles within the collection, but then there were all these techniques that I wasn’t very knowledgeable in. It was amazing to see curatorially.”

The exhibition’s curation draws from Ithra’s curving and cohesive architecture. The core thread of the exhibition touches upon the rapid modernisation of cities in the Arab world, such as with Zeinab Abdel Hamid’s Popular District (1956), a painting that shows the newly installed tramway in juxtaposition with traditional carts and street vendors. It then moves to explore how artists were reclaiming local craft practices and revisiting Islamic art legacies.

Breakout spaces, meanwhile, delve into the works and techniques of artists such as Binzagr, Al-Munajjed, Farhat as well as the Wissa Wassef Art Center.

“We wanted to have a free-floating curation,” Homs says. “Visitors can see the exhibition however they want, understand different points of entries and these complex relationships.”

Farah Abushullaih, head of Ithra museum, says Horizon in their Hands directly responds to Ithra’s mission of “preserving legacies, amplifying diverse voices, and inspiring dialogue between past, present and future.

“Through this institutional collaboration that foregrounds under-represented narratives in Arab art, this exhibition is set to become a milestone in Ithra’s mission of nurturing creativity and cultural dialogue across the region and beyond.”

Horizon in their Hands is running at Ithra Museum until February 14