Inside a small Nasa-style control room in Oxford in the UK, a group of scientists are trying to solve a puzzle that could answer the world's energy needs forever.

They seek the key to unlocking fusion energy — cleaner, more efficient and less risky than nuclear fission, which the world's nuclear plants currently use.

Their work, at a time of turmoil in the energy markets and spiralling household bills, has never been more crucial.

Just last week, Tokamak Energy, based in Oxford, and the UK’s Atomic Energy Authority struck a five-year deal to develop a brand new fusion reactor.

First Light Fusion

“There’s a clean power gap,” says Dr Nick Hawker, chief executive and co-founder of First Light Fusion, also based in Oxford, which has raised £77 million ($86m) from investors to scale up its research.

“If we’re going to fill it with fossil fuels, we won’t hit our net-zero targets. Fusion is one of the solutions for filling that gap.”

The National visited First Light Fusion's research lab for a closer look.

How it works and why it matters

In simple terms, scientists want to recreate the reaction that powers the Sun.

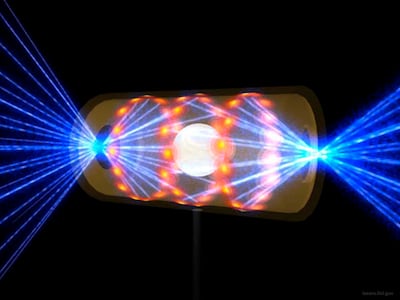

On Earth, this involves harnessing a huge amount of electrical power and discharging it to create an electromagnetic force inside a hi-tech machine. This, in turn, accelerates a small disc to speeds of up to 20km-per-second.

That would make it one of the fastest-moving objects. But it doesn't go far. It slams into a target just 10mm in front of it.

In the target there is liquid fuel, and when it is struck it creates such pressure and temperature that nuclear fusion can happen.

The challenge is to tip the balance so that you create more energy than it cost you to start the process. And no one has managed it yet.

First Light Fusion wants to change that.

Much less problematic than nuclear fission when it comes to waste production and worst-case scenario risks, fusion could offer potentially limitless supplies of clean energy.

First Light Fusion, which was spun out of the University of Oxford in 2011, achieved fusion in a result announced this year that was verified by the UK Atomic Energy Authority.

Dr Hawker said nuclear fusion could “make a massive contribution” to the world’s energy needs — but not immediately, he admits.

There is, he says, “an urgent need to be decarbonising”, which means huge investments are needed in renewable sources of energy such as wind and solar power now.

However, the world’s energy demands are continuing to increase, with the US Energy Information Administration expecting them to have risen by 47 per cent by 2050.

The machine

Much of the work at the company’s headquarters in Oxford Industrial Park, north of the city, centres on M3 (Machine 3), a £3.6 million (Dh14.2m) unit described as one of the largest pulsed power facilities in the world.

Radiating out from the centre of M3 are six spokes made up of a total of 192 capacitors, devices that store electrical charge.

It is used for the high-speed firing process outlined above.

If operating industrially, lithium flowing inside the target chamber would be heated up by the energy released by fusion. Through a heat exchanger, it would turn water to steam, which would generate electricity through a turbine.

First Light Fusion says that in a power plant, this process would take place twice a minute, with each target producing enough electricity to power a home for about two years.

Scaling up

First Light Fusion now aims to scale up the technology.

To that end, plans are in place to build, at another location, a much larger machine called M4, which will be 80 metres in diameter.

It will also have 40 times as many capacitors as its smaller sibling and should be capable of sending the projectile at much higher speeds. The aim is to have this up and running in the second half of the decade.

Meanwhile, there are, in Dr Hawker’s words, “30 to 40" other companies working on fusion using a variety of other approaches to heat the fuel. These include creating electric fields or using a combination of compression and heating.

Given that it does not produce greenhouse gases or long-lasting radioactive waste, nuclear fusion may seem like the ideal answer to the world’s energy needs.

'For solving climate change, it's irrelevant'

But not everyone is convinced.

Prof Niklas Höhne, founder of the NewClimate Institute in Germany, says “it will come online far too late and will be far too expensive” to contribute to the greenhouse gas emissions cuts that he says are essential now.

“For solving the climate crisis, it’s irrelevant,” he says. “To make up this large difference, fusion is simply expensive and doesn’t work yet.”

Costs of wind and solar power will probably continue to fall, he says, while fusion’s costs may not plummet as fast.

“Just look at nuclear fission, the current nuclear power,” Prof Höhne said. “In the last 30 years, the costs have not declined and are much, much higher than wind and solar.

“Why put effort in a future technology when we don’t know whether it will work, when we know wind and solar does work?”

Adding to the energy mix

While accepting that the jury is still out on fusion’s commercial viability, other energy analysts think it may make an important contribution.

“If it can be made to work on a commercial scale, then fusion clearly would have a role to play. We don’t know to what extent it can work,” says Bob Ward, of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, part of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

“We certainly need to do more research and development and investigations with fusion, because if it does work, it promises potentially lots of cheap, clean energy in the future.”

Dr Hawker is keen to emphasise that fusion is not a substitute for immediate investments in wind and solar power.

But he does think that in the second half of this century, a time when many experts suggest the world will need to achieve negative emissions, fusion could come into its own.

The lower risk profile (he says a complete plant meltdown would create only one ten thousandth of the hazard of the Fukushima disaster) means that fusion is likely to be cheaper than nuclear fission and could be competitive with other technologies.

He envisages 100 megawatt (MW) plants that each cost less than $1 billion to build and have a levelised cost of electricity ― a measure that includes the plant’s lifetime costs ― of about $45 per megawatt hour.

Ultimately, many forms of nuclear fusion power could make it through research and development to become viable commercially. Dr Hawker sees First Light Fusion as being among the handful of front-runners.