Hosni Mubarak, the former Egyptian president who was swept out of office by the Arab uprisings nine years ago after almost 30 years in power, died on February 25, 2020. He was 91 years old.

One of his two sons, businessman Alaa, tweeted earlier this week that his father had been admitted to intensive care. He asked supporters to pray for his father but did not say what was ailing the former air force commander and war hero. Security officials said he was being treated at a Nile-side military hospital in the Maadi suburb of Cairo, the Egyptian capital.

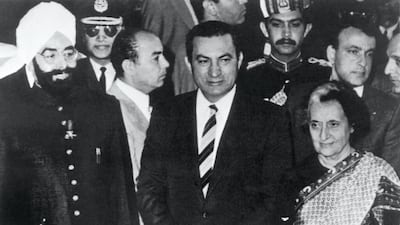

Mubarak, who hailed from a village in the Nile Delta, unexpectedly assumed the presidency of the most populous Arab nation when President Anwar Sadat was gunned down by Islamic militants during a 1981 military parade.

Then a diligent vice president, Mubarak was seated next to Sadat when the latter was gunned down. He escaped with a superficial hand wound. After such a close brush with death, Mr Mubarak cancelled the annual pomp-filled military parade marking the 1973 war with Israel.

Still, Mubarak was the target of at least six assassination attempts during his decades in power, including one in Addis Ababa in 1995 and another in the Egyptian coastal city of Port Said.

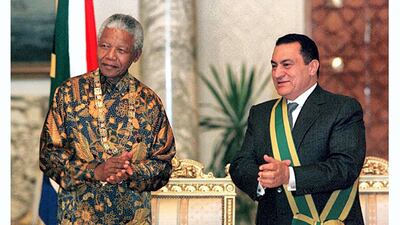

Mubarak’s knack for surviving assassination attempts was matched by his ability to hold on to power, building up a reputation as a reliable western ally, while ensuring the loyalty of the powerful military.

That worked well for Mubarak, but his grip began to loosen in the last decade of his rule. His other son, Gamal, rapidly climbed the ladder of the ruling National Democratic Party and positioned himself as his father’s heir apparent. That succession scheme did not sit well with a powerful military accustomed to presidents emerging from its own ranks.

The final straw did not come from the military but from a nascent opposition movement led and fuelled by youths outraged by the beating death of a young man by the police in the coastal city of Alexandria. An 18-day popular uprising began on January 25, 2011.

Faced with continued protests, a breakdown in law and order and a series of crippling strikes, Mubarak halted his attempts to stay in power through making political concessions and delegated his newly appointed vice president, intelligence chief Omar Suliman, to announce that he was stepping down and handing the reins of power to the military.

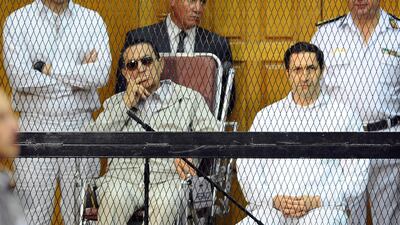

It was not long afterwards that Mubarak was charged alongside his security chief and several top policemen with the shooting deaths of some 800 protesters during the 2011 uprising. That case, from which he was later acquitted, brought Mubarak to the public eye for the first time since he stepped down. He sat in the defendants’ cage in an upright stretcher and wearing sunglasses, an image that he maintained during a series of court appearances for several years after his removal from power.

In 2014, Mubarak and his two sons were convicted of embezzlement, sentenced to three years in prison and fined millions of pounds. All three were eventually released for time already served.

All told, Mubarak faced six years of legal proceedings since his detention in April 2011. For the entirety of this period, he was in either a prison hospital or prestigious military medical facilities where he was treated with the respect and dignity befitting a former president.

Mubarak has continued to have the support and adulation of a significant segment of society after he left office, with many crediting him with the high GDP growth of his years, record number of foreign tourists and a foreign policy that won Egypt reliable friends in the West.

By stepping down, however, Mubarak is given credit for sparing Egypt what could have been a bloody struggle similar to that in Libya, where a 2011 uprising against Muammar Qaddafi turned into a years-long conflict.

Mubarak also refused to flee the country, selecting to stay put and face what comes his way, a stand that won him accolades as a patriot and a loyal soldier.

"This dear nation... is where I lived, I fought for it and defended its soil, sovereignty and interests. On its soil I will die. History will judge me like it did others," he told the nation in a televised address during the uprising.