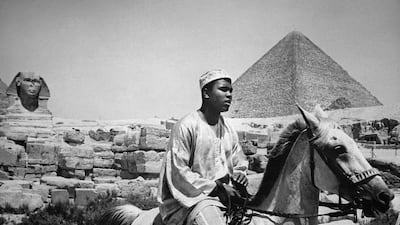

CAIRO // Of all Muhammad Ali’s travels in the Muslim world, his 1964 trip to Egypt was perhaps the most symbolic, a visit remembered mostly by an iconic photo of the boxing great shaking hands with a smiling Gamal Abdel Nasser, Egypt’s nationalist and popular president.

It was a mutually beneficial meeting.

For Nasser, he was viewed with suspicion and mistrust by the United States, but revered across much of Africa and Asia for his support of movements fighting European colonial powers. For Ali – the new heavyweight boxing champion – being received by one of “imperialist” America’s chief enemies announced his arrival on the global stage as a powerful voice of change.

The boxing genius and revolutionary political views of Ali, who died Friday at age 74, emerged when America’s civil rights movement was in full swing and the Vietnam war raged on, sharply dividing Americans.

In those years, the Muslim world was experiencing a post-colonial era defined by upheaval, with most developing nations taking sides in the Cold War, allying themselves to varying degrees with the United States or the Soviet Union.

His conversion to Islam won him the support of many across the region. Three years later, his refusal to serve in the US army in Vietnam – “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong” – and his subsequent loss of the world title resonated with Muslims, many of whom saw that conflict as the epitome of America’s global tyranny.

“Muslims wanted a hero to represent them, and Clay was the only Muslim champion ... No other Muslim athlete managed to achieve what Clay did ... Thus, he was a symbol for Muslims,” said Mohammed Omari, an Islamic law professor in northern Jordan’s Al Al Bayt University.

In a Muslim world with a seemingly infinite number of people called “Mohammed Ali” the Louisville, Kentucky, native was mostly referred to as Muhammad Ali Clay – ironically retaining one of the “slave” names that he argued so hard and long for people to drop after he became a Muslim.

It was the diversity of the causes embraced by Ali during his lifetime – from the civil rights movement and anti-war activism to global charity work and dealing with Parkinson’s disease – that has won him a large following among a wide range of admirers in the Muslim world. To them, he meant different things.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II wrote that Ali “fought hard, not only in the ring, but in life for his fellow citizens and civil rights”.

“The world has lost today a great unifying champion whose punches transcended borders and nations,” King Abdullah wrote on his Twitter account. Accompanying his tweet was a photo of Ali, King Hussein, Abdullah’s late father, and US president Gerald Ford – all in tuxedos.

Yet others in the region remember him for his boxing first, not his religion or politics.

“To me, he was primarily a boxing role model to follow,” said Mohammed Assem Faheem, a three-time youth heavyweight champion in his native Egypt.

“When I watched tapes of his fights, I focused on two things: His footwork and defence tactics. I could not copy them, they were too good for me,” said Faheem, 26 who is better known by his nickname, Konga.

To boxing coach Nashaat Nashed, 55, who is also a member of Egypt’s Coptic Christian minority, Ali was an inspiration. “God created him to box, not for anything else. I owe it to him that I took up boxing and that I fell in love with the sport.”

Nizam Zayed, 48, a Palestinian handyman at a gym in the West Bank city of Ramallah, said he watched most of Ali’s matches during the old days of black-and-white television.

“My generation liked Muhammed Ali because he was very good at boxing and because his name was Muhammed Ali and he was a Muslim.”

Pakistan’s cricket legend-turned-politician Imran Khan, writing a series of tweets mourning Ali’s death, described the boxer as the “greatest sportsman of all time” and a man of strong convictions. “Sportsmen have a limited career life span in which they can earn and Ali sacrificed it for his beliefs with courage and conviction.”

In Iraq, where Ali visited in 1990 to secure the release of 15 Americans who had been taken hostage by Saddam Hussein, retired heavyweight boxer Ismail Khalil mourned “the greatest”.

“Today marks the death of a great champion. It is sad day for the world of boxing. This champion does not represent America only, but the entire Islamic world too.”

* Associated Press