TOZEUR, TUNISIA // The Jeep rumbles to a stop and as the engine dies, a vast silence rises up from the silvery salt flats; our final footsteps crunch on the sand as we approach a place of pilgrimage.

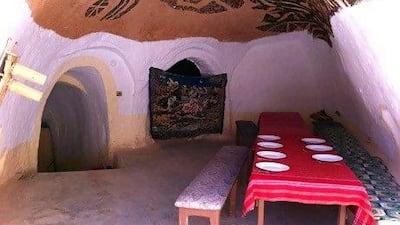

Here, with the setting sun gleaming on its white dome, stands the Lars Homestead, the boyhood home of Luke Skywalker, and beside it the crater where he gazed moodily into the double sunset in the first Star Wars film, A New Hope.

"It's this igloo in the middle of nowhere," says Mark Dermul, a Star Wars fanatic since he first set eyes on Skywalker in 1977. "I remember the first time visiting it, I had to switch off the fact that I am in Tatooine. I had to say to myself: 'You are on planet Earth.'"

Despite the uncanny feeling of being in the iconic fantasy land of Tatooine, Mr Dermul was indeed on Earth, in the deserts and canyons of southern Tunisia.

He was one of thousands of devotees who haunt the film sets, imagining themselves in what Skywalker's mentor Obi-Wan Kenobe called a "wretched hive of scum and villainy", dodging evil Storm Troopers and hot-tempered Wookies.

Mr Dermul has a job in finance back home in Belgium, but his hobby is to visit Star Wars locations. He came to this one in 2001, after the house had been rebuilt for the prequel trilogy in the 1990s, and led groups of enthusiasts here in 2003 and 2005.

When he returned in 2010, he was saddened by its decayed state. Afraid that it would moulder into the sand like the original, built in the 1970s, he dreamt up a renovation plan that stumbled against a revolution but was ultimately welcomed by local people.

He launched a website where fans could donate to fund the preservation. Within 10 months, people from Texas to Tokyo had given US$10,000 (Dh36,700), and an application for permission was lodged with the Tunisian government.

But last year, in a turn of events not without parallel in the Star Wars narrative of freedom versus totalitarianism, Tunisians rose up and forced out president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali. In the chaos, the plans seemed under threat.

"It may sound a little selfish," says Mr Dermul, "but my first concern was uh-oh, the project is going to die. Only in the second place did I think about the turmoil the people were going through - but I can understand their need for democracy."

His worries were short-lived. His permission came through in October, as a new government formed and tried to address a 50 per cent drop in the vital tourist industry. He completed the work in May.

Mr Dermul's interest in their unusual heritage was welcome, said Kamel Al Boubi, of the branch of the National Office of Tunisian Tourism in the nearby town of Tozeur.

"Tozeur has become a famous place because of Star Wars," said Mr Boubi. He said that the filming was great for business, from the lush hotel where the megastars stayed, to people like his friend Kamel Meshrawi, who was an extra in the 1970s.

"I had a costume with a face like an octopus," says Mr Meshrawi, wriggling his fingers to give the effect. "I had long hair, a big belly and feet like a duck." He played one of the monstrous rogues in the bar where Skywalker meets his comrade Han Solo, and remembers frightening townspeople.

"I was trying the costume, to see how long I could last in the sun," he says, chuckling. "And a woman from Tozeur, she was crossing the road and she saw me and fainted. She thought that a monster had come!"

Initially, he and about 100 other extras did not fully understand the point of the outlandish costumes, nor of pretending to watch imaginary space craft speeding by.

But they appreciated the work and eagerly participated when the crews descended upon them again in the 1990s. Otherwise, Mr Meshrawi has worked in a hotel but is now unemployed after it, and several others, closed down as tourism ebbed.

Tozeur is home to another icon of freedom - the poet Abu Al Qasim Al Shabi, whose poem which begins: "If one day a people desire to live, then fate will answer their call," became an anthem of last year's uprisings. His tomb, with his most famous words inscribed in gold, is next to the tourist office.

But for hotel owners, drivers and gaunt men selling trinkets to tourists at the film sets, the revolution has taken away their business and its ideals are as bewildering as the struggle of the Jedi against the Empire.

Mr Meshrawi says that he would love the film crews to return so he can work as a fixer or reprise his role as an incidental alien. "We would like them to come back tomorrow," he said. "Why wait?"

foreign.desk@thenational.ae