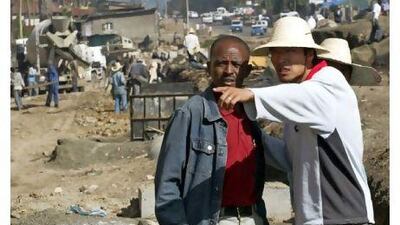

The baggage lounge at Addis Ababa's Bole airport is filled with activity as the Ethiopian Airlines flight from Beijing arrives. Young Chinese men, casually dressed in flannel trousers and shirts, gather around the luggage belt, lifting off large suitcases and heavily wrapped boxes. A crowd of these arrivals, perhaps 50 strong, queue up together outside to be collected by a fleet of waiting minibuses.

These young men are not tourists. They live in Ethiopia, part of the influx of Chinese labour in the last decade that has changed the face of Africa. In states across the continent, Chinese communities have sprung up. Some are based around the myriad infrastructure projects that the world's emerging superpower is implementing. Many are simply trading on a small scale, importing buckets and work tools, the low-cost essentials that power rural life on this continent.

This was the year that China became the world's second largest economy, overtaking its Asian neighbour Japan and prompting much soul-searching around the world over the imminent arrival of the Chinese. But in Africa, the Chinese have already arrived.

Trade between Africa and China topped $100 billion this year -more than between the United States and Africa - and China is the single biggest manufacturer of infrastructure on the continent. The Chinese make things, things that African nations desperately need. Roads and railways, hospitals and schools, pipes and dams; Chinese companies have built them all.

Everywhere one looks on the African continent - and especially in resource-rich countries - China is developing extensive trade links. Oil, of course, ranks high. Chinese companies are active in Nigeria, which is the continent's largest oil-producer, as well as Angola and Sudan. But the copper mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, the iron ore mines in South Africa, and the forests of Cameroon; all send their bounty to China.

Listen to the words of Julius Ole Sunkuli, Kenya's ambassador to China, as repeated by leaked diplomatic cables: "Africans [are] frustrated by western insistence on capacity building, which translated. into conferences and seminars. They instead preferred China's focus on infrastructure and tangible projects."

From one perspective, China is becoming a rich country. The shopping avenues of New York, Dubai and Tokyo are full of well-off Chinese buying high-end goods. Yet the Chinese government still likes to present itself as a developing country, full of solidarity for the developing world. Countries in Africa strive to emulate China's phenomenal growth over the past decade. And China helps them achieve it, for example by increasing the number of African students it admits to its universities. Education, infrastructure, immigration: China offers all of these things to Africa. No other single country can boast as much.

Such prosperity comes at a price. China's foreign relations have long been based on a principle of political "non-interference". Good governance, one of Africa's most difficult challenges, comes a distant second to business imperatives. That means that when China does business with unsavoury African regimes such as Zimbabwe, Chinese weapons are used against the people of the country.

Moreover, the benefits that come to African governments and big business do not always trickle down to citizens. Chinese products have devastated local industries, such as the manufacturing sector in Nigeria, and Chinese companies have caused ructions elsewhere: in Zambia, whose mining industry has received more than $400m in investments from the Chinese government, Chinese managers at the Collum coal mine in the southern Sinazongwe province were reported to have shot and wounded 11 of their workers during a protest this year. The Chinese presence has also provoked some political parties to campaign on no-foreigner platforms.

But it was among its Asian neighbours that China's presence was most strongly felt this year. China's rise to its position as Asia's dominant economy, confirmed in August, raised urgent questions in Japan, which worried that China's economic clout would soon be matched by provocative behaviour. The following month, that fear appeared to come true.

In September, a Chinese trawler collided with two Japanese coastguard ships near a group of disputed islands. Japanese police arrested the captain for deliberately ramming the vessels, triggering a serious diplomatic struggle between the two countries. China suspended ministerial exchanges with Japan and stopped the export of rare minerals.

The row lasted over two weeks, before Japanese prosecutors released the captain and tensions fizzled out. Japanese politicians that warned the exchange made their country look weak, but it was China that came out of the scuffle worst. For its Asian neighbours, its softly-spoken assurances of a peaceful rise began to look hollow.

Earlier in the year, the Chinese military declared its "indisputable sovereignty" over the South China Sea, after America's Secretary of State argued the sea was part of the US's "national interest" in the region. The altercation with Japan over the islands suggested that China's claims to the sea would be vigorously asserted, with at least diplomatic force.

Elsewhere this year, China's diplomatic muscle was also called into question regarding North Korea.

In March, a South Korean warship sank near the disputed border with North Korea. Investigators later concluded that a torpedo from a North Korean submarine was to blame. Yet China refused to condemn Pyongyang. Tensions between North and South remained high and reached a peak in November, when North Korean troops shelled a small southern island, killing two civilians. In the biggest crisis for the two countries since the end of the Korean War, China, the only regional country that can exert influence on North Korea, merely called for restraint on both sides.

The incident was damaging all around. Asian countries that rely on America for their security glimpsed its impotence over this issue. At the same time, the episode hinted that even China may not be able to rein in Pyongyang.

If China's rise is being felt in Africa and Asia, what about in America, the country that is likely to be its biggest rival? Political advertising provided a glimpse.

In the run-up to the autumn's mid-term elections in the United States, a conservative lobbying group ran an advert on American television, envisaging a future where China dominates the United States. America turned its back on the principles that made it great, intones a sinister Chinese politician against an Orwellian backdrop, "so now," he says, "they work for us". His audience of young Chinese leaders laugh delightedly.

The ad was an attack on big government but its other message was clear too - China's power is rising and America's is fading. Americans feel this in their hearts and their leaders fear it: according to leaked diplomatic cables, Hillary Clinton once asked rhetorically, "How do you deal toughly with your banker?" China currently holds around $870bn in US treasury bonds, more than any other country. As China's wealth grows, such questions will become more insistent.

But it isn't the growth of China's economy that worries its neighbours and rivals, but what it means to do with its new wealth. African countries are pleased with the investment their new best friend brings - even though it may not be good for them in the long term. Asian countries recognise that China's growth is good for them as well - but worry about its military expansion and its tough talking. And America is having, for the first time in its history, to confront a rival that it cannot challenge militarily without destabilising a world system it relies on for its wealth. The past 12 months may have raised these questions, but it will be many years before there are clear answers.

In the Chinese calendar, this past year was, appropriately enough, the Year of the Tiger. As Asia's largest tiger grows, its roar is increasingly heard around the world, unsettling neighbours and rivals alike.

Faisal al Yafai is an award-winning journalist and a Churchill Fellow for 2009/2010.

Ethiopia: Crouching lions, hidden dragon

China's influence on Africa continues to expand but this year the nation's diplomatic stances have betrayed worrying signs of volatility.

Most popular today