Income inequality in India may be at its highest level since 1922, according to a new research paper, with the top 1 per cent of earners making 22 per cent of all income — a ratio that has risen rapidly over the last three decades.

India Income Inequality, 1922-2014: From British Raj to Billionaire Raj?, published last week by French economists Lucas Chancel and Thomas Piketty, is based on the latest income tax data.

Mr Piketty is known for his 2013 best-selling book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, which argues for reform to reduce income inequality around the world. He was dubbed a "rock-star economist" by the Financial Times. Mr Chancel is the co-director of the World Inequality Lab and of the World Wealth and Income Database at the Paris School of Economics.

"According to our benchmark estimates, the share of national income accruing to the top 1 per cent income earners is now at its highest level since the creation of the Indian income tax in 1922," said the report.

“The top 1 per cent of earners captured less than 21 per cent of total income in the late 1930s, before dropping to six per cent in the early 1980s and rising to 22 per cent today."

_______________

Read more:

Mumbai's businesses - and India's economy - count the cost after devastating floods

India demonetisation figures deal blow to Modi

India: 70 years of independence

_______________

The trend matches the circumstances of India’s economy, which was brought under strict state control in 1947 when the country became independent. The process of liberalising the economy only began slowly in the mid-1980s before picking up pace the following decade.

The metrics that track inequality followed economic reforms closely. In the 1990s, for instance, there were no Indians on Forbes’ annual list of billionaires; today there are 101.

Other indices have also confirmed the rising inequality in India. A 2016 study by two Indian economists of the data collected by the state’s National Sample Survey Office showed that the richest 1 per cent of Indians hold 28 per cent of all the wealth in the country. In 1991, it was just 11 per cent.

Another report, by the investment bank Credit Suisse, says the richest 1 per cent hold as much as 58 per cent of India’s wealth.

India’s Gini coefficient — which measures income distribution in a country - rose from 45 in 1990 to 51.4 last year, indicating a growing gap between rich and poor. China’s Gini coefficient rose over the same time period as well, from 33 to 53.

“In some larger countries [such as China and India], spatial disparities, in particular between rural and urban areas, explain much of the increase” in the coefficient, a report by the International Monetary Fund said last year.

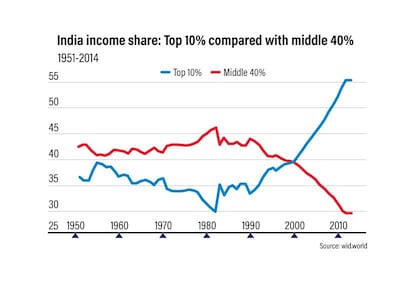

The economists argue that "Shining India" - the name given to the past two-and-a-half decades of swift economic growth - has mostly benefited the wealthiest 10 per cent of India’s population. The middle 40 per cent were, in terms of capturing their share of national wealth, better off between 1951 and 1980, they said.

“India in fact comes out as a country with one of the highest increases in top 1 per cent income share concentration over the past 30 years,” according to the report by Mr Chancel and Mr Piketty.

James Crabtree, a fellow at Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, confirmed Mr Chancel and Mr Piketty’s observation that liberalising the economy triggered a drastic divergence in incomes and wealth.

"India's economic reopening to globalisation has been a big factor in rising inequality, as has rapid urbanisation, and an economy that rewards the highly skilled," Mr Crabtree, the author of an upcoming book,The Billionaire Raj, about Indian's political economy, told The National.

“India's government hasn't done enough to counteract these factors — for instance, by ensuring the wealthy pay their taxes, or by investing in basic social services like schools and hospitals, to help people at the bottom.”

The widening gap in economic status has been accompanied by a gap in opinions about how to tackle it.

One school of economic thought believes that developing countries, such as India, should focus primarily on economic growth and worry about inequality at a later stage.

According to the theories of Simon Kuznets, first published in the 1950s and 1960s, the forces of an open market in a developing economy will naturally first widen and then decrease wealth inequality.

Another school of thought, championed by the Nobel-winning economist Amartya Sen, holds that India has not done enough for its wide, deep base of poor people, and that its policies ought to focus more on human development than pure growth.

Mr Crabtree believes that India’s growing inequality is a “big problem” and that economic growth and human development can be pursued simultaneously.

“Countries in east Asia that managed to escape poverty and become prosperous almost always did so while staying much more equal than India is now,” he said. “The risk is that India's situation will worsen as it grows richer over the coming decades, making it much harder to reverse later, as countries like Brazil and South Africa have discovered.”