Hazar, an 11-year-old Syrian girl from Aleppo, dreams of being a doctor and a teacher — but instead often finds herself collecting potatoes in Lebanon’s fertile Bekaa Valley to help her family pay their spiralling rent.

Her mother Shamsa, 32, who has five other children, says the monthly rent at their refugee camp on the outskirts of Bar Elias has increased from 100,000 Lebanese pounds to 700,000, meaning Hazar and her sister have to work in the fields to support their family.

Although Hazar is not registered with the Lebanese public school system, she has been able to take classes offered by the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) — but is not able to attend as much as she would like because financial demands on the family mean she has to take on work.

“I want to realise my dream. I want to be a teacher because I want to educate children so that they can also realise their dreams,” Hazar said from her home.

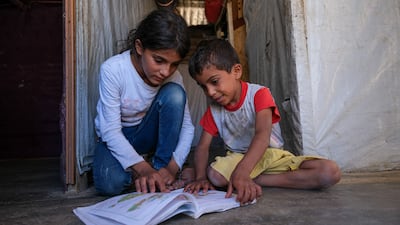

Basic maths and Arabic are among the classes she is taking at a nearby NRC education centre, which is also attended by children at the camp.

On a typical working day Hazar and her sister leave home at 6am with a local community leader on a lorry, to arrive at 8am. They usually work until about 1pm.

“It’s very tiring. When I arrive home, I shower and then go to sleep because I have no energy left,” she said.

Like many young Syrian refugees In Lebanon, Hazar faces many barriers in accessing education.

Public schools are oversubscribed, children lack the necessary documentation, families cannot afford the transport or related costs and some allege that prejudicial treatment against Syrian refugees makes them feel uncomfortable.

Lebanon’s population of about six million includes as many as 1.5 million refugees who have fled the decade-long war in neighbouring Syria. The UN estimates 90 per cent live in extreme poverty.

Hazar's family fled the conflict and arrived in Lebanon in 2016. They first left Aleppo for more rural areas, leaving for Lebanon when the fighting came close again. Shamsa was pregnant at the time and says her child was born deaf because of the trauma she was undergoing at the time.

Lebanon itself is facing a devastating economic crisis that began in 2019, with many Lebanese people themselves plunged into poverty amid widespread shortages of basic essentials.

The country’s economic downturn has led to increased calls from Lebanese authorities for Syrian refugees to be returned, a move condemned by the UN and rights groups.

In Lebanon, thousands of public sector teachers have been on strike at times this year to demand better salaries. A continuing teacher strike has forced the government to delay the start of the school year.

Some, like 15-year-old Wael, have attended informal, unlicensed schools. While they do provide education, some do not give certificates that can be used to demonstrate the level of education the child has achieved. Wael's parents tried to register him at a secondary school in Bar Elias, but were told there was no space.

The family is from Daraa in south-west Syria and have been in Lebanon since 2013. Wael's parents have nine children, ranging in age from four months to 19 years old, and they live together at their home in Bar Elias. Some of the children previously attended public school.

“They used to work in the rain and get sick because we couldn't afford the transport,” said Wael's mother, Rabiaa, 40.

“I decided that because they were getting sick it would be safer for them to stop going.”

She said the road was dangerous too.

“We put them in another public school, but always had issues with the teachers. They used to tell them things like 'Syria won't be proud of people like you'," she said.

Wael's father, 43-year-old Ahmad, used to work in construction. But last year he was stabbed during an altercation and was left with an injured lung, meaning he can no longer work. This meant Wael had to step in.

Wael too has recently received online classes from the NRC after leaving a school a few years ago following a disagreement with a teacher who he says mistreated him.

“We were with the teacher on the bus, he screamed at me and he hit me. I jumped out of the window and continued walking home. Then I started working,” Wael said.

“I want to continue school, but I don't see how it is possible. It's impossible because I need to work,” said Wael, who works on an ad hoc basis in a job related to tiling and earns between 50,000 and 75,000 Lebanese pounds a day. Before the economic crisis, 50,000 Lebanese pounds a day would be around $33 before the crisis but worth just $1.5 today.

“I was very happy at the sessions at NRC. My friends were also registered. I was very happy and then I had to stop to go to work.”

Children 'have to go to work'

Rabiaa says the family has moved home nine or 10 times in Bar Elias since arriving in Lebanon.

“Even now, we are facing a lot of difficulties in this house,” she said, referring to the lack of water, electricity and their monthly rent of 1,600,000 pounds ($1,061 on the official rate, or around $45 on the black market that is more reflective of the real value of the Lebanese currency ).

The Covid-19 pandemic has also had a significant effect on the Lebanese education system, said Maureen Philippon, the NRC's Lebanon country director.

“If there is one sector where we cannot overstate the impact of Covid, it is education," she said.

"Every teacher or school principal I've met is very clear that the capacity of the kids to concentrate, to learn, has decreased tremendously because of the three years of Covid.”

The NRC says there are serious “structural concerns” that prevent refugee children getting an education — from paying for transport to being able to afford stationary. The schools themselves are also under significant financial pressure.

Hazar says her mother tells her it is the financial strains that mean she cannot go to school as much as she would like.

Shamsa, her mother, says she is always happy when her children are given the opportunity for education.

“I really care that they get to learn something, but at this moment they cannot be consistent because they have to work," she said.

“If they were registered at a public school, they would have learnt so much more and had more opportunities for better jobs. They wouldn't be illiterate. They would see something and understand on the phone. They would be able to write their names.”