Pope Francis will arrive in the UAE at a time when relations between Muslims and Christians are both complex and contradictory. Yet ambiguity has characterised the relationship between the world’s two biggest faiths ever since the time that the Prophet Mohammed entered into discussions with a group of Christians who visited him in Makkah almost 1500 years ago. Muslim-Christian relations have, over the centuries, oscillated between conflict, coexistence and conversation.

Ours is a time in which tensions between the two faiths – whose members constitute almost half the world’s population – have reached a low point that has seen some reaching for comparisons with the Crusades, the Inquisition, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire or the excesses of European colonialism. And yet – thanks to the goodwill of men such as Pope Francis, together with a host of leaders of Muslim and Christian communities at the local level – it is also the time of a new global friendship between members of the two religions.

Christianity and the Prophet Mohammed

Muslims and Christians have never been quite able to make up their minds about one another. In his early years the Prophet Mohammed saw his teaching as very much in continuity with the traditions of Judaism and Christianity. He expected that Jews and Christians, having Abraham and Moses as common ancestors, would accept his prophetic message as a continuation of their own. All were “People of the Book” who had received revelations of God in written texts.

Christian writers disagreed, often vehemently, but the disagreements were largely theological. In practice, relations between Muslims and Christians were good. While pagans in conquered territories were expected to convert to Islam, Christians and Jews were given the status of “dhimmi”, which allowed them to practise their religion in private and govern their own communities. In return they paid a poll tax. Though Byzantine polemicists insisted that Islam was a plot to destroy the Christian faith, other Christians saw Islam as “the rod of God’s anger” to deliver them from the oppressive rule of the Orthodox in Byzantium.

Muslim rulers in Egypt and Syria would employ Christians in important positions. Greek was used rather than Arabic as the first language of the Umayyad court. In the ninth century Islam inherited the learning of the Hellenist tradition. Muslim leaders even founded an academy to translate the works of Greek philosophy, science and medicine into Arabic. In this way many of the classic texts of the Greek and Roman world were preserved during Europe’s Dark Ages and were eventually restored to the West at the Renaissance.

Distinctly Islamic contributions in the spheres of law, architecture, science and technology were similarly transmitted to Europe. There is even a suggestion that the treatment of religious minorities during the Ottoman Empire – where four religions, known as millets, were officially recognised: Islam, Orthodox Christianity, Armenian Christianity and Judaism – suggests that toleration within a pluralist society was an Islamic rather than a western invention.

The Crusades

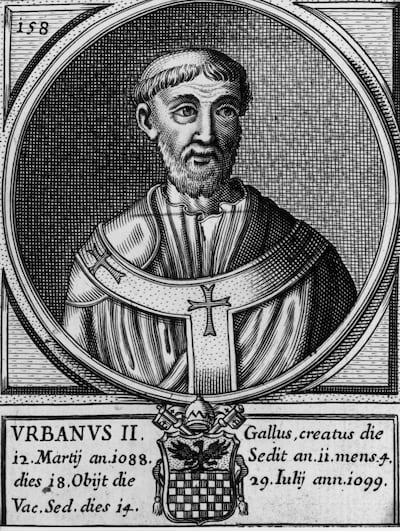

During the Middle Ages relations became more strained. Competing dynasties vied for power in both the Muslim world and in Charlemagne’s Holy Roman Empire. As the medieval period progressed, relations deteriorated. In 1095 Pope Urban II launched the first of a series of the Crusades, which were to scar relations between the two great faiths – inflicting a wound from which the two cultures have never fully recovered.

One of the great myths about the Crusades is that they were launched for primarily religious motives. The truth was more complicated. As with so many conflicts between Christianity and Islam over the millennium that followed, territorial and economic considerations stoked the religious rhetoric. In fact, the First Crusade came about through a complex set of factors including the desire of Pope Urban to reinforce the power of the papacy. Christian rulers were also ambitious to increase their sphere of military, political and commercial influence. Merchants and bankers were as significant as knights-at-arms and footsoldiers. But the religious bombast, which was used to stir ordinary Christians to fight, also served to intensify the medieval Christian vision of Islam as a moral threat.

Historians now agree that there was no moral equivalence in the initial behaviour of the competing armies. When the Crusaders stormed Jerusalem in 1099 they left few Muslim men, women or children alive. Where Islam made distinction between the dhimmi and the pagan, Christianity did not; Saint Bernard – from whom the crusader Frederick Barbarossa received a cross before battle – ruled that killing for Christ was not homicide but malecide (the extermination of injustice) and pronounced, "To kill a pagan is to win glory, for it gives glory to Christ." The Crusaders even massacred Eastern Christians, either through ignorance or prejudice about notional heresy.

Small wonder that Pope John Paul II, to mark the Millennium in 2000, issued an apology for the Crusades and an era in which the Christian cross came to represent what the former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, called “the language of the powerful, the excuse for oppression, the alibi for atrocity”.

By contrast, when Salah al-Din (Saladin) recaptured Jerusalem in 1187, during the Third Crusade, his Muslim troops were as magnanimous in victory as they had been tenacious in battle. Christian civilians were spared; so were most churches and shrines. That contrast explains why it was such a blunder for former United States President George W Bush, after the September 11 attacks in New York and Washington in 2001, to unthinkingly deploy the word “crusade” when talking about America’s intended response. One moderate Mufti said that the words of President Bush “recalled the barbarous and unjust military operations against the Muslim world”. Osama bin Laden and his followers – both before and after 9/11 – took delight in referring to all western military forces as “crusaders”.

The peace treaty signed by Salah al-Din and Richard the Lionheart, King of England, placed Jerusalem in Muslim hands but allowed Christian pilgrims access to the city. It was good for the economy. As so often was the case in the centuries to come, territory and treasure, rather than religion, were the realpolitik that governed Muslim-Christian relations.

Co-operation and cohabitation

Yet even amid the tensions of the Crusades there were more friendly counter-currents. During the Fifth Crusade, in 1219, the Christian saint Francis of Assisi crossed the battle lines to visit the Muslim leader Sultan al-Malik al-Kamel, nephew of Salah al-Din. Entering into enemy territory, St Francis was arrested and taken to the Sultan who, perceiving his captive to be a holy man, received him with courtesy.

After three weeks of dialogue, Francis left Egypt. Thereafter the saint was respectful of Muslims to the point that he encouraged Christians to emulate them in prayer and prostration, and to join Muslims – and others – in service to all, setting aside the differences in their religions. Francis specifically told his followers not to try to convert the followers of the Prophet Mohammed. In a quid pro quo the Sultan later granted control of Bethlehem and parts of Jerusalem – and a corridor to them from the sea – to Christian worshippers, reserving the Dome of the Rock and the Al Aqsa Mosque for Muslims, and the Temple area for Jews.

Again, it was under Muslim rule that the most harmonious period of cohabitation between the three Abrahamic faiths took place. In medieval Andalusia, in the southern part of Spain, for around 250 years – between 756 and the turn of the millennium – Muslims, Christians and Jews lived in untroubled proximity and even mutual appreciation.

It was called the convivienca (living together). Christians and Jews were given prominent positions in the court of the 10th century Caliph as translators, physicians, engineers and architects. Jewish and Christian entrepreneurs flourished away from the feudal rigidities of Christian Europe. The Archbishop of Seville had the Bible translated into Arabic. Muslims, Christians and Jews studied together at the university of Cordoba, founded in 968. The classical texts which had been translated into Arabic in the early medieval period were rendered back into Latin and Greek, paving the way for the efflorescence of learning which was the European Renaissance.

By the 14th and 15th centuries Christian theologian John of Segovia and humanist philosopher George of Trebizond were both campaigning for a Christian-Muslim peace conference. The Catholic theologian Nicholas of Cusa, in “perhaps the most tolerant examination of Islam in the late medieval West”, explored the idea of the ultimate unity of all religions.

Shared vision and points of divergence

It is not difficult to understand the basis of that visionary notion. Islam shares many common elements with Christianity, and with Judaism. All are monotheist, believing in a single God.

In each faith God intervenes in human history, acting through prophets and angels. In each religion divine revelation is recorded in sacred texts. All share the God of Adam, Abraham and Moses. Each believes it has a special covenant with God.

Peace is central to the teachings of all three faiths. All hold that humankind will be held accountable on Judgment Day when eternal reward and punishment will be meted out. Muslims, like Christians, believe that Jesus will return to earth before the day of judgement.

Muslims also venerate Jesus and his mother Mary (who is mentioned more times in the Quran than in the New Testament). Both faiths believe in the virgin birth of Jesus. Both believe that he performed miracles such as healing the blind and raising the dead.

But there are many points of difference. Muslims believe that though Jesus was condemned to die on a cross he was miraculously saved from Crucifixion. They believe, like Christians, that Jesus is alive with God, yet they insist he was human not divine. They believe, like Christians, in the Holy Spirit – but suggest that the Spirit is the Angel Gabriel (who revealed the Quran to the Prophet Mohammed over a 23-year period) rather than the third person of a Trinitarian God. The Trinity, to Muslims, represents a division of God’s oneness, and is therefore a grave sin bordering on polytheism. Where internal Christian disputes have focused primarily on theology, in Islam the major debates and disagreements have been on religious law and practice.

Again, all this emphasises a deep ambivalence on the part of Muslims towards Christians. A number of verses in the Quran and the sayings of the Prophet Mohammed, the Hadith, call for Muslims to treat Christians and Jews with respect as fellow recipients of God’s divine message. The Quran tells Muslims that they will find Christians “nearest to them in love” yet it warns them not to make them close friends. These caveated, or even contradictory, impulses have manifested themselves in Muslim attitudes to Christians over the centuries – and the incongruity has been reflected back in Christian attitudes to Muslims.

Colonisers and missionaries

The fall of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Christian empire, to the Muslim Turks in 1453 signalled the end of an epoch. It was mirrored in Spain by the final expulsion of Muslims from Andalusia at the end of the same century. As the medieval world gave way to the early modern one, the focus of Muslim-Christian relations shifted significantly.

The three major Muslim empires of the age – in Ottoman Turkey, Safavid Persia and Moghul India – grew internally weaker and began to decline. At first Europe took no advantage of that – it was preoccupied by its 17th-century internal wars of religion. But later, after its Industrial Revolution, it grew in strength economically, technologically and militarily and established colonies in Muslim lands in Algeria, Tunisia, Egypt, West Africa, India and South-East Asia. European nations such as Greece, Serbia and Romania won independence from Muslim rule.

The European colonial authorities replaced Muslim and indigenous cultures and systems with those of western missionaries – and later secular educators – who entrenched negative perceptions of Islam. The writer Edward Said later characterised these as “Orientalism”: a way of looking at Arab-Islamic peoples and their culture as exotic, backward, uncivilised, irrational and dangerous. By comparison, western values were portrayed as enlightened and progressive.

Many in the Muslim world felt humiliated by a colonial system that undermined their society, education, religion and culture. Some joined militant anti-colonial resistance organisations, which grew in strength after the Second World War end campaigned for independence from the colonial yoke.

A number of Christians, too, were uncomfortable with this subordination of Islam. At the Second Vatican Council in the 1960s, the Catholic Church shifted its attitude to other faiths, and Islam and Judaism in particular. Vatican II issued a document, Nostra Ætate, which urged Christians and Muslims “to strive sincerely for mutual understanding” and “make common cause of safeguarding and fostering social justice, moral values, peace and freedom”.

The Catholic Catechism went further. It asserted: “The plan of salvation also includes those who acknowledge the Creator, in the first place amongst whom are the Muslims; these profess to hold the faith of Abraham, and together with us they adore the one, merciful God, mankind’s judge on the last day.”

Protestant Christianity was marginally less sympathetic. Its founder, Martin Luther, had insisted that any post-Christian religion was false by definition. Its passionate insistence that salvation came only by faith in Jesus Christ made it less accommodating, though Protestants and Muslims shared an iconoclastic dislike of the religious images so beloved by Catholics.

The man who was perhaps the most prominent Catholic leader in the 20th century, Pope John Paul II, was a strong advocate of better relations between Christianity and Islam. The first Pope ever to visit a mosque, in Damascus in 2001, he told a massive crowd of Muslims in Casablanca: “We believe in the same God, the one God, the Living God who created the world … In a world which desires unity and peace, but experiences a thousand tensions and conflicts, should not believers come together? Dialogue between Christians and Muslims is today more urgent than ever. It flows from fidelity to God. Too often in the past, we have opposed each other in polemics and wars. I believe that today God invites us to change old practices. We must respect each other and we must stimulate each other in good works on the path to righteousness.”

He set up a special Department inside the Vatican to deal with interreligious dialogue.

Two sides of the new world order

It might have been expected that the economic globalisation of the late 20th century would improve relations between Muslims and Christians even as it eroded traditional social and religious structures. Global communication improved. Increased immigration around the world brought Christians and Muslims into closer proximity with one another. At least a third of all Muslims today live in non-Muslim countries, some 30 million of them in Europe. Societies have become multicultural, multiracial and multireligious.

But in the Muslim world many resented the increased influence of the West and its value systems. Bodies such as the World Bank, the IMF and the UN Security Council seemed to control Muslim economies in the developing world – where young Muslims generally received a western-style education. The West’s backing of the state of Israel, with the support of right-wing evangelical Christians, was an added problem, even though many other Christians were more sympathetic to the Palestinians.

Muslim societies, with their different range of understandings of Islam, reacted to this western dominance in different ways in the final decades of the 20th century. Some sought to reconcile Islam with the contemporary world. Others saw the answer in a secular pluralist state. Others turned to an Islamist revival, advocating a more theocratic model which integrated Sharia and state law – as happened in Iran, Pakistan, Sudan and Afghanistan, and is having an increased influence in Turkey, Nigeria and the world’s largest Muslim country, Indonesia.

Some see the world as increasingly polarised, and fear the “clash of civilisations” predicted by American academic Samuel Huntington in 1996. It is not hard to find evidence that seems to support this – with the violent activities of groups such as the Taliban in Afghanistan, Boko Haram in Nigeria and the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq. After the attacks of 9/11 fear of Islam grew rapidly in the US where analysts suggest that right-wing evangelical Christians and others spend more than $40 million (Dh147m) a year producing wilfully Islamophobic material. Attitudes have hardened in Europe too, with offensive cartoons ridiculing the Prophet Mohammed appearing in newspapers in Denmark, France and elsewhere. Under the aegis of the French official policy of laicite a ban has been placed on the public wearing of the hijab.

After terrorist bombings in New York, Madrid and London – and repeated attacks on Christians in Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq and Syria, which threatened to drive Christianity entirely from the lands that were its cradle – it is not hard to argue that Christian-Muslim relations are at a low point not experienced since the days of the Crusades.

And yet it is Muslims who are the chief victims of the increased violence in the Middle East. Today some 70 per cent of all refugees in the world are Muslims. A minority, although a sizeable one, has managed to escape by moving to Europe – a development which, thanks to the incitement of populist politicians, has served to put new strains on relations between Islam and Christianity.

But men such as Pope Francis show there is another side to this story. Since he was elected in 2013 this pope has encouraged the Catholic Church to intensify its dialogue with Islam. Muslims, he has told Christians, are their brothers and sisters.

In what amounts to a manifesto for his papacy, the document Evangelii Gaudium (The Joy of the Gospel), he tells Christians they must "avoid hateful generalisations" about Muslims. Instead, they should remember that, despite "disconcerting episodes of violent fundamentalism" the truth is, "authentic Islam and the proper reading of the Quran are opposed to every form of violence". Fine words were not enough, he insists. Fruitful dialogue with Islam means that "suitable training is essential for all involved". Actions are required, too. "Christians should embrace with affection and respect Muslim immigrants to our countries in the same way that we hope and ask to be received and respected in countries of Islamic tradition," though he adds, pointedly, "I ask and I humbly entreat those countries to grant Christians freedom to worship and to practise their faith, in light of the freedom which followers of Islam enjoy in western countries".

Other Christian denominations are responding to contemporary tensions in a similar way. The Anglican Church has established initiatives for Muslims and Christians to study Scripture together, discuss the social challenges the two communities face, and identify common action against violence, poverty and injustice. The Orthodox Church has set up a programme to explore the theologies of Christianity and Islam. Other groups of Christians are focusing their joint Muslim-Christian initiatives on contemporary ethical questions about the role of the family, gender relations, new scientific and medical technology, and the environment. In the US thousands of churches have now initiated study programmes on Islam and joint projects to build housing for low-income families. There has been a dramatic increase in courses on Islam in North American colleges and universities.

But the visionary figure of Pope Francis is in the vanguard. He has even said he is open to the possibility of dialogue with the men of violence in Islamic State if that might bring peace. Never count anyone as lost, he said. “Never. Never close the door. It’s difficult, you could say almost impossible, but the door is always open.”

Paul Vallely is author of George W Bush and the Christianisation of the War in Iraq, published by the British Council in Re-imagining Security. He also wrote the biography Pope Francis – Untying the Knots, published by Bloomsbury