ABU DHABI // A summer campaign is being launched to dismantle a hidden city on the rooftops of the capital. But many of the people living in the cheap rooms are saying that they have nowhere else to go. Owners of about 200 buildings were recently served with warnings. Only 76 owners complied by removing the unlicensed construction.

A dozen buildings are still being monitored; 111 offenders will be taken to court for failing to fix the problems. More notices are to come, according to the municipality, which aims to enhance the capital's image and improve environmental health and safety. Measures to "rid the city of all forms of distortion" such as rooftop shanties will extend to areas where they are "quite rampant" such as Al Bateen and Hadbat al Zafranah, said Owaidah al Qubaisi, the acting executive director of municipal services.

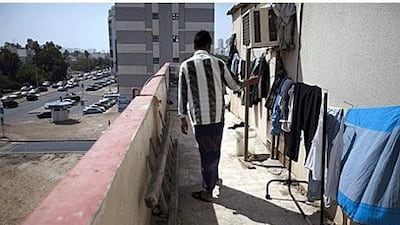

Regular inspections are planned for both neighbourhoods. It is not good news for the people who live on the rooftops. ND Kawsar's makeshift dwelling, which he shares with 20 other bachelors, is no penthouse. Broken satellite dishes, sacks of rubbish and laundry lines roast under the sun outside his door. Inside, exposed wires droop from his ceiling. There are no fire-safety devices, nor is there any means of escape other than a stairwell wide enough for a single-file exit.

"No safety. The level of danger is high. We cannot take a fire," said Mr Kawsar, 27, a typist. "But where can we go? Abu Dhabi is expensive. The good flats are only for families." Mr Kawsar, who lives in Hadbat al Zafranah, blamed the shortage of affordable housing in the city as the real issue forcing residents such as himself to cheap and unlicensed rooftop flats. "We are working in small shops, restaurants, some for construction companies," he said. "It's so difficult for us. If the baladiyah (municipality) close the room, where [do] I go? Sleep in the road?"

On a salary under Dh2,000 (US$545) per month, his Dh450-a-month accommodation above the weathered three-storey building overlooking Al Saada Street is all he can afford. The landlord plans to raise his rent by Dh50 next month, he added. "If we are taking a new building, we are paying maybe more than Dh1,000. How we will pay?" he asked. "If the baladiyah want to close, first they have to increase our salary. Money is the problem."

Down Airport Road, Ummary Hossain agreed high housing costs gave her and her husband little choice but to share their rooftop quarters with another Bangladeshi couple. One kitchen, two bedrooms and one bathroom were enough for four adults, said Mrs Hossain, 25. But her main concern was the risk of an electrical fire sparking from a tangle of wires and satellite dishes just metres away from her doorstep.

"This is very unsafe for fire," she said, adding that the rent for the flat was Dh4,000 a month. "For one year, this is not cheap. But rooftop is cheaper than other rooms." The couple want to start a family, but they decided their living conditions were unfit for raising children. After nine months there, they will leave in September because the building is to be demolished, Mrs Hossain said. Infestation and fires are major concerns. Helicopters had to airlift a young girl and two adults to safety in August 2008 after a fire broke out in a rooftop shanty atop a 16-storey apartment block on Airport Road.

A reporter revisited the four rooftop dwellings last week at the Fathima Supermarket. Mukundan K, a construction worker from Kerala living there, was aware of the previous fire, but was not worried as long as he had a place to live. He said four workers shared each flat. The municipality urged owners of villas and buildings to co-operate with authorities, blaming "investors who only care about making windfall gains" for putting people's lives at risk by renting out ramshackle rooms.

Mr al Qubaisi said other major offences reported included the unauthorised building of room partitions, leasing villas to more than one family, and improper linking of plumbing or electrical lines.

Offenders who fail to respond to the municipality's warnings after a grace period will be taken to court and fined. The removal of the dwellings will also be at the cost of the offender.

The municipality did not specify the fines or lengths of the grace periods.

mkwong@thenational.ae