It was a typical weekend for Ali Hassan al Shehhi: a 15km hike deep into the mountains of Ras al Khaimah in a pair of well-worn flip-flops with every prospect of losing a toenail or two. As a member of the formidable mountain tribe Al Shehhi, he prizes the privacy of his ancient village and way of life. But this time, in an unprecedented gesture of trust and hospitality, he allowed a reporter and photographer from The National to accompany him home.

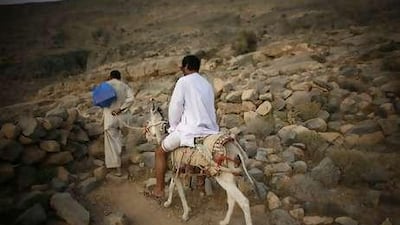

With a gun resting on his shoulder, a jerz - a small axe-head on a long handle - in his right hand, and an air of nonchalance, Mr Shehhi loped effortlessly along a difficult unmarked trail to his village in the Baqal area of the Hajjar mountain, urging his fellow travellers to keep up. "Yala, yala, it is very close, just around the corner." Five hours later, the party of six - Mr Shehhi, Sheikh Mohammed bin Sultan al Khateri from the desert tribe, The National's team and two Pakistani workers, each carrying about 50kg of food and drinks on the head - arrived in the isolated village of Baqal.

To be fair, the workers had already beaten the rest of the team to the top of the mountain by at least two hours. Mr Shehhi, Sheikh Mohammed - who took a wrong turn - the reporter and the photographer ended up wandering in the dark with flashlights, along steep rocky terrain crawling with creatures of the night. It was the end of a knee-jarring hike that had been preceded earlier in the afternoon by a 90-minute drive from RAK airport. For the last few kilometres, the car sped along a newly cut, unsurfaced road that twisted and turned until it came to an abrupt stop. Outside, the air was noticeably cooler. The temperature had fallen by nearly 10 degrees to 33°C.

Less than a year old, the road, which will have a tarmac surface when completed, is part of a government initiative to open up the region for visitors. "Before, we walked up all of this," said Mr Shehhi, who speaks in a distinctive accent that even fluent Arabic speakers find hard to understand. "You are spoiled." Historians have traced the dialect to the pre-Islamic Sabaic language from southern Arabia and ancient Yemen, Many Emiratis have other theories, that it is derived either from the language of the Portuguese, who explored the region, or from ancient Persian.

"I don't know why I speak like this, but I know only the mountain people speak like this and so we can communicate to each other without outsiders understanding us," Mr Shehhi said. The difficulty of communicating was one reason for the presence of Sheikh Mohammed, who helped to translate some of the trickier words and also acted as a mediator. "We are friends," said Mr Shehhi of Sheikh Mohammed, adding: "only friends of friends are welcome".

Years of harsh mountain life have left Mr Shehhi, 45, with features as rugged as the peaks he regularly scales. The father of 10 children is a man of few words, all of them concise. His tribe's tradition, he believes, is to protect the mountain from strangers. "We are of the mountain and the mountain is of us," he said, quoting a proverb handed down from his ancestors. Along the mountain path, ancient carvings could be seen, mostly of animals that appeared to be goats and large mountain cats, now extinct. Other strange, triangular shapes recorded a way of life that was now long gone.

"I don't know what they mean, but the drawings were here before my grandfather's grandfather," Mr Shehhi said. Also visible was an old cemetery with tombstones made from local rocks, shot through with colour. The stones were blank, either because no inscriptions had been carved or because time had eroded them. Mr Shehhi described the graveyard as "thousands of years old". "We bury our people in the valleys nowadays," he said. The life of the mountain tribes is still nomadic and revolves around the seasons. During the hot summers, when water is scarce, they move from their villages at high altitude to the valleys and coast to farm vegetables and harvest dates or fish. In the autumn they move back to the foothills for trading, while their animals graze on the pasture. In the winter they return to the mountains to cultivate crops of wheat and barley and wait for the rains of the new year.

In such a hostile environment, water is a precious resource and is stored in large cisterns known as burka, or ponds, which hold supplies for drinking and bathing, as well as irrigation. Over generations, the tribes have become masters of their environment, keeping goats for milk and meat, but also discovering the secrets of local plants, including wild figs and a nut known as meez, which tastes similar to a pecan. It was knowledge Mr Shehhi chose to share with his fellow travellers, stopping from time to time to pick samples. Ripping off a piece of one plant, he declared "this cures fever", moving off before anyone could question him further. A distant shrub, he claimed, "cures wrinkles", adding: "That is what my wife believes, anyway". "Eat. They give energy," he said of another plant, before forging ahead at a pace that left everyone else behind. During breaks, he urged the group onwards and upwards, saying: "Come on, it is easy. Just follow me." In fact the trip was anything but easy, and even less so after Mr Shehhi pointed to a sharp drop where a cousin had fallen to his death. "He was following a goat," he explained. After several hours on the trail, even Sheikh Mohammed's patience was beginning to wear thin. "Where is your house, already?" he asked.

"I swear it has wheels and is moving away as we are getting closer." Back came the inevitable reply: "Just around the corner." Suddenly, though, the journey was over. It was too hot to sit inside Mr Shehhi's one-room house of rocks and cement. Instead, he and the two Pakistani workers, Saed Khan and Lander Khan, pulled out a couple of thin mattresses and placed them outside to sit on. The two Khans, both 30, had left their home in Peshawar to work as "lift men" for the mountain tribes. "They call me on my mobile before they come here and so I prepare myself to carry things for them," said Saed, who has walked the trail to the mountains for 16 years. Saed helped Mr Shehhi build one of his homes, carrying buckets of cement up the mountain for over a month. The two men set up the evening meal of a watermelon cut into triangles, oranges, traditional rolled up mountain bread, labnah and dates. The drinks included the untreated rainfall from the cistern and two big bottles of 7-Up. There was also coffee, boiled on natural gas because there is no electricity or running water in the village. Even the reception of mobile phones is uncertain, with the network constantly switching between the UAE and neighbouring Oman.

Reminders of the old ways were all around. Not far from the house was a traditional mill, made of two circular stones, for crushing wheat. After washing from a bucket, the two Emirati members of the party entertained themselves by shooting their guns at a neighbouring mountain peak and boasting about their skills. "My bullet went further than yours," Mr Shehhi claimed. Sheikh Mohammed disagreed and fired again. The shots were not the only sounds disturbing the peace of the surroundings. In the distance could be heard the noise of bulldozers and lorries, working in nearby quarries. "They are breaking away pieces of our souls," said Mr Shehhi, with anger in his voice. It is a sentiment shared by many in the mountain tribes. For Mr Shehhi, the prospect of a quarry any nearer his home would led to al Nadba or the "war cry" from his people. "I will never let them come near my village," he said, standing up with his gun and pointing in the direction of the lights of a distant quarry. Later he talked more about the history of the mountain people of the UAE, saying that after the union in 1971, many opted to move to modern homes along the coast. Others, like his tribe, still make the arduous journey back to the mountain villages every winter.

The Shehhi tribe traces its roots to Al Azd tribe in Yemen in the second century AD and is the mother tribe of others, such as the Al Dhuhoori, Bani Shmaily, Habus and Al Qiyasha tribes. It is a way of life that is gradually vanishing. "We used to all fight with each other, now all the mountain tribes are united, and what makes us unique is fading away," said Mr Shehhi. Sleep eventually came on the mattresses under a clear blanket of stars and the moon. The night was filled with the noise of whining mosquitoes, replaced in the morning by the buzzing of honey bees. "The mountain bees are tough like us," Mr Shehhi said. With the village deserted for the summer, there was little more to do than head back down the mountain. This time the trail was shorter, but more difficult and far steeper. "The trails are not marked, only the Khans and the tribesmen know how to get here," the guide explained.

Although it took only three hours, the return seemed much longer for those with sore feet and knees and not enough rest. Even Mr Shehhi was feeling the strain, but still declared "almost there", even though no one believed him. But suddenly it was the end of the trail, with Mr Shehhi's son, Faiz, waiting with the car. Faiz, 25, will marry in the autumn but said: "My wife and I won't be coming up the mountain. We are going to make a life for ourselves in a modern house in RAK." Handing out cans of Pepsi and bottles of water and loading the weary party into the car, he had an admission to make. He will be taking his bride for a honeymoon in Switzerland. "I am a mountain man, so I still like to be near a mountain in my life, but a greener one," he laughed.