A new satellite launch is going to test the technology needed to look for the gravitational waves the famed physicist predicted.

People making it to the age of 100 are a perfect excuse for a party – after all, it is not everyone who manages it.

But a scientific theory that is still vibrant and thriving after a century is rarer still. Many of today’s supposed breakthroughs look tired and lose to younger models after a few years at best.

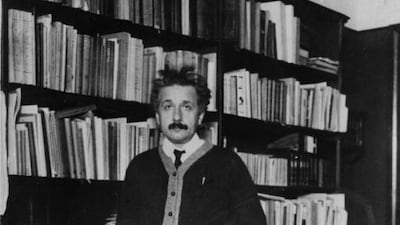

Not so Albert Einstein’s theory of gravity – or to use its wilfully opaque scientific name, the General Theory of Relativity.

Last week “GR” was the focus of global scientific celebrations marking the centenary of its public unveiling.

And small wonder: over the four lectures he first gave in Berlin in 1915, Einstein revealed a vision of reality that still boggles even 21st-century minds.

Yet it answered a childlike question – one left unresolved by all previous attempts to understand gravity: what is it?

To the ancient Greeks, gravity was a natural tendency of objects to seek the centre of the cosmos.

About 2,000 years later, Isaac Newton described gravity in terms of a force generated by mass, and captured its behaviour with his famous “inverse square law”.

Yet when asked exactly how this force kept the planets orbiting the Sun through the vacuum of space, Newton confessed he had “not as yet been able to discover the reason”. He dismissed further debate by insisting he was not prepared to guess.

What Einstein unveiled in 1915 showed the wisdom of Newton’s refusal to speculate. No amount of 17th-century logic could have led him to Einstein’s vision.

To Newton, it was simply an article of faith that space and time are absolute and immutable. Einstein showed that they are not – and that this unlocks the mystery of the nature of gravity.

According to GR, matter is embedded in space and time and actually distorts it, rather like a cannon ball sitting on a vast rubber sheet.

What the ancient Greeks called a “tendency” and Newton described as a “force” is really an illusion. There is no invisible force field reaching through the vacuum of space making one object move towards another.

Einstein said that what we were seeing was the distorting effect of mass on space and time, leading to effects we interpreted to be a force of attraction.

GR does more than tidy up our picture of reality, however. Its equations predict effects that can be put to observational test, such as the slowing of time by gravity, and the deflection of light passing by massive objects.

And incredibly, after a century of scrutiny by scientists using ever more exacting techniques, GR remains undefeated. It has passed every experimental test.

This impressive track record was at the heart of last week’s celebrations, including a gathering of leading experts on GR, at Harnack House in Berlin, where Einstein once lectured.

But hanging over the proceedings was one small cloud. It centred on a phenomenon predicted by GR that Einstein himself struggled to believe in: gravitational waves.

According to the theory’s equations, violent events involving colossal masses – such as the explosion of a gigantic star – trigger ripples in the fabric of space-time. These gravitational waves are more than a mere cosmic novelty, however. They have the potential to become a whole new way to observe the Universe.

Such waves could reveal the death throes of massive stars, the clash of black holes and even probe the Big Bang itself, seeing events before light was generated. Some theorists have even claimed that the waves could carry the imprint of the Universe before the one we inhabit.

The trouble is, gravitational waves have never been observed – at least, not directly. Studies of collapsed stars provide strong evidence for their reality but attempts to detect them directly have so far drawn a blank.

One explanation could be that scientists have goofed in their calculations of how gravitational waves are emitted. Perhaps such cataclysmic events are rarer than thought, or are less powerful sources of waves.

Answers may soon emerge from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (Ligo) in the United States.

This scientific leviathan consists of two sets of vacuum tubes 4 kilometres long set up in Louisiana and Washington, down which laser beams are fired.

Gravitational waves sweeping through the Earth are expected to distort the beams but the effect is incredibly small – 10,000 times smaller than the width of an atomic nucleus, hence the use of duplicate tubes at two sites thousands of kilometres apart, to help rule out false alarms.

After years of trying and failing to find gravitational waves, Ligo was shut for an upgrade. It has just begun operating again with a tenfold boost in sensitivity.

Meanwhile, European scientists on Thursday launched Lisa Pathfinder, a mission to test the feasibility of one day building a colossal space-based gravitational wave detector. The hope is this will finally confirm Einstein’s prediction, although no one knows for sure.

Even Einstein struggled with the theory of gravitational waves, at one point throwing a hissy fit with a scientific journal, whose expert claimed to have found a mistake in his calculations (which indeed there was).

Even so, a straw poll among the experts attending the Berlin conference would doubtless reveal complete confidence that gravitational waves do exist.

Paradoxically, the same poll would also reveal complete confidence that Einstein’s theory is not the last word on gravity. While it has passed every experimental test thrown at it, GR is known to have an Achilles heel.

In the 1960s, theorist Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking proved that the equations of GR go haywire in conditions that exist in the core of black holes and at the instant of the Big Bang.

The effect is like dividing any number on a calculator by zero. GR gives the mathematical equivalent of an error message, called a “singularity”.

Theorists think the way forward is to create a new theory of gravity, combining GR with quantum theory, which governs the physics of the subatomic world.

But no one has succeeded in marrying these two notoriously complex theories. The signs are that bringing about the marriage will require the collective efforts of an army of theorists.

As such, last week’s celebrations may also prove to be a wake for the idea of the lone genius.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham