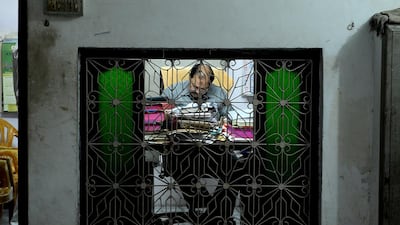

Zainab Begum Alvi and her band of young helpers hunch over baskets filled with tobacco flakes and dried leaves, trying to roll a thousand dirt-cheap cigarettes a day at the behest of India’s powerful bidi barons. “I have to do it, no matter what, even if I’m not well,” says Alvi, who earns 70 rupees a day, a little over a dollar, for her 12 hours of toil. “There is no other work than this,” added Alvi, a gaunt woman from the impoverished northern state of Uttar Pradesh who says she is in her 50s.

About 70 million Indians smoke the hand-rolled bidis. They outsell their filtered, paper-bound rivals by eight to one, giving the industry’s bosses a clout that critics say accounts for the recent shelving of plans for larger health warnings on packets. “There is no medical evidence that bidis cause cancer,” said Shyama Charan Gupta, one of the three legislators on the committee and who heads a company that produces one of the industry’s best-selling brands.

Bidis have long been marketed as a “natural” product. But campaigners argue they can be more dangerous than normal cigarettes as they are smoked in greater quantities. Up to 900,000 Indians die every year from causes related to tobacco use and researchers have warned that figure could reach 1.5 million by the end of the decade. While a packet of 20 normal cigarettes can cost in excess of 150 rupees, a bundle of 15 bidies can sell for as little as five rupees, their price kept low by favourable tax rates.

Most bidi smokers are poor men living in rural areas but up to 90 per cent of the roughly 5.5 million bidi rollers are female and a quarter are children. Continuously exposed to tobacco dust, many suffer from high rates of respiratory diseases including tuberculosis and asthma. Laws enacted in the 1960s and 70s to improve the welfare of workers only encouraged manufacturers to fragment production into smaller units to escape regulation, campaigners say. Estimates of annual production range from 750 billion to 1.2 trillion sticks, suggesting a sector worth billions of dollars.

In backroom factories such as Alvi’s home in Uttar Pradesh’s Kannauj district, children often work alongside relatives to help them meet quotas. “I don’t like it,” said Alvi’s 14-year-old niece Seema. “I want to go to school for longer, but I can’t because of bidi rolling,” said Seema, who dreams of becoming a teacher. Nearby at the New Sarkar Bidi Factory - a ragtag operation in a derelict shell of a building - men and young boys work in near darkness packing bidis at lightning speed. General manager Quazi Naseem Ahmed, who says his company turns over 400 million rupees ($6.4 million) a year from 16 factories, insisted the boys only appeared underage as they had been weakened by years of hard work. Ahmed acknowledged it was a tough life but also rejected talk of a link to cancer. “They are weak, they are dirty, they get tired, so they have low immunity but they don’t get diseases like TB or cancer,” he said.

* Nina Shah for AFP