ABU DHABI // An Abu Dhabi scientist says he has discovered a treatment for cystic fibrosis that could boost the life expectancy of sufferers.

Dr Wael Rabeh, a professor at New York University Abu Dhabi, said the discovery had the potential to help between 50 and 80 per cent of sufferers.

Dr Rabeh said the research, published last week in the scientific journal Cell, was a new step in treating the recessive genetic disorder.

"It is ready for a clinical trial," he said. "A drug based on this research will be able to help patients survive this illness if they take it throughout their lives."

Cystic fibrosis, which is mainly found in Caucasians, affects one in every 2,000 to 3,000 newborns in Europe and about 70,000 people worldwide.

It is caused by a genetic mutation in a protein known as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) that controls the hydration of the lungs' cells.

Without the proper amount of moisture, the mucus surrounding the cells becomes thick, sticky and dry, blocking the airways and making it difficult to breathe.

Over time, the mucus build-up can result in serious lung infections and most patients do not survive past their 30s.

The German expatriate Christian Guenther, whose son Jakob, 3, was diagnosed with cystic fibrosis when he was born, said it was a shock to find out that he would outlive his own child.

"It's a situation you just don't want to be in," said Mr Guenther, who lives in Dubai.

There were about 194 cases of endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases, which include cystic fibrosis, in the UAE in 2010.

Dr Rabeh said his research had found a way to increase the activity of the CFTR protein carrying the genetic defect, from less than 5 per cent to 80 per cent.

"People think of protein as one unit but it actually has different compartments that all work together," he said.

"This is the first study on any protein that shows how unique and important this particular interaction is."

Dr Rabeh also found a way to restore up to 80 per cent of the CFTR's functions by stabilising the genetic mutation, which is found in 90 per cent of cystic fibrosis patients.

It is hoped the discovery can act as the missing component to existing treatments, which only restore about 15 per cent.

Dr Rabeh said he was in talks with pharmaceutical companies to begin clinical trials in the hope of creating a drug treatment.

Nicola Wilson, an Irish woman who has a five-year-old son with cystic fibrosis, said such a drug was something for which all parents of sufferers hoped.

"It will impact so many lives if it really does work," said Mrs Wilson, who has lived in Dubai for 21 years. "Imagine if he could live an entire life."

Her son, Noah, takes 10 pills with his breakfast every day, which includes a handful of antibiotics, multi-vitamins and other tablets that help him absorb food. They include pancreatic enzyme supplement capsules.

Noah also needs to follow a strict daily exercise regime to loosen up the mucus in his lungs.

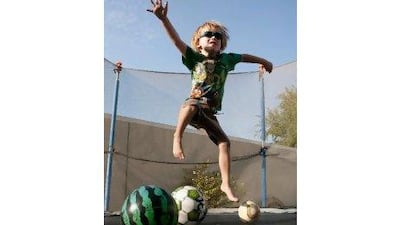

He plays football, takes swimming lessons and spends hours at his Mirdif home jumping on the trampoline.

Blowing air into balloons or playing the trumpet also helps to generate the necessary vibrations in his chest.

"To him it's all fun, but to us he's doing what he needs to do," said Mrs Wilson.

Dr Rabeh's work is the third time this month that scientific research in the UAE has broken ground in the treatment of diseases.

Scientists at the Sharjah Medical Research Institute and the Sharjah Academy for Scientific Research recently announced they had found 15 compounds that have the potential to fight cells that cause Alzheimer's disease, and three compounds that could fight cells responsible for the progression of breast cancer, in two separate three-year studies.

Dr Lihadh Al Gazali, a senior consultant in clinical genetics at UAE University, said the cystic fibrosis research sounded promising but it was more important to focus on preventing the disease in the first place.

"I hope this new research can bring change for patients with the disease. At the moment, the current treatments in the market are not satisfactory so it's better to prevent it," she said.