Astronomists are holding on to hope that a star's mysterious dimming could be caused by a huge structure placed around it by aliens. But they are guarded in what they say, in case it's again just interference from a microwave oven.

Take a look at the night sky this evening, above the north-west horizon near the huge cross-shaped constellation of Cygnus the Swan. You’ll be looking in the direction of a distant star codenamed KIC 8462852.

And possibly, just possibly, someone – or something – will be looking straight back at you.

This faint star is the focus of global attention by astronomers because it is behaving very strangely – so strangely that some suspect we may be witnessing the work of aliens.

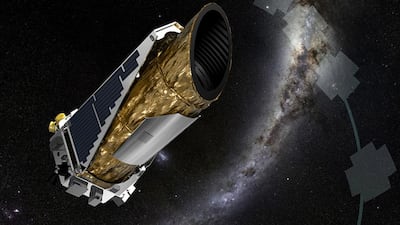

First observed by Nasa’s orbiting Kepler telescope six years ago, KIC 8462852 once seemed as boring as its name. About the same age as the Sun, it is bigger and brighter and lies almost 1,500 light years away.

It was duly filed away among the 150,000 stars observed as part of Kepler’s search for planets orbiting other stars.

To reveal their existence, computers scour the telescope’s data looking for telltale dips in the light from the stars as the otherwise invisible planets pass across them.

It’s a method that has so far revealed the existence of more than 1,000 such planets, including eight that could be habitable.

But alongside the computers, the Kepler team has opened its data archive to thousands of human volunteers, asking them to scour it for anything odd that the computers weren’t programmed to detect.

And in 2011, several of these amateur planet hunters flagged up KIC 8462852 for something very odd indeed.

Every so often, the star’s brightness plunged – in one instance by more than 20 per cent – only to recover again.

That’s not so unusual. Centuries ago Arabic astronomers found a star in a constellation near to Cygnus whose brightness plunges by 70 per cent and does so like clockwork every 2.9 days.

Unable to explain its behaviour, they dubbed the star Algol, “the Head of the Demon”.

Astronomers have since identified many such variable stars, with their changing output the result of internal changes or external effects.

In the case of Algol, the cause is now known to be the dance of three close-packed stars, whose combined output varies with the number of stars in view.

What’s strange about KIC 8462852 is that its output doesn’t make any sense.

Since 2009, it has undergone sudden and irregular dips in brightness. As such, they can’t be the result of one or more planets in orbit around it.

Looking at the data more closely revealed that the star does not have the nice, neat U-shaped fall in brightness, as expected if nice, neat objects like planets are passing across its disc.

The star itself, meanwhile, seems perfectly normal, spinning on its axis alone in space.

So what is going on?

An international team of astronomers has scoured the entire Kepler archive looking for anything similar, and come up empty.

This has led the team, whose leader is Dr Tabetha Boyajian of Yale University, to come up with some explanations.

One possibility is that KIC 8462852 may have run into a barrage of comets, the dust and ice of which is causing the irregular dips in brightness.

But Dr Boyajian and others are now examining another possibility: that the dips are caused by huge structures positioned around the star by aliens.

Scientists involved in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or Seti, have long speculated that aliens might reveal their presence by setting up so-called megastructures around their nearest star, for power generation or even habitation.

Known variously as Dyson swarms or statites (static satellites), these complex structures are expected to consist of huge light-gathering panels. As such, their passage across the face of KIC 8462852 could create the strange light pattern observed.

Dr Boyajian and her colleagues are now drawing up detailed plans of how to put the alien megastructure theory to the test.

Everyone is hoping for a repeat of the strange dips, the most recent of which was in February 2013. Telescopes around the world are now watching the star, waiting for the next dip to start.

Once detected, alerts will be sent to much larger telescopes fitted with equipment able to analyse the event in detail.

Dr Jason Wright of Pennsylvania State University says the pattern of the dimming may reveal the size and shape of the objects responsible, which could be range from specks of dust to asteroid-sized structures.

Meanwhile, observations at different wavelengths could also reveal their chemical composition.

Dr Wright believes the combined data should be enough to reveal whether there’s any merit in the alien megastructure theory. Astronomers have already turned a network of radio dishes towards the star to listen for any signals.

Dr Wright puts the chances of aliens being responsible as small, although not zero.

“My philosophy of Seti is that you should reserve the alien hypothesis as a last resort,” he wrote in his personal blog. “It would be such a big deal if true that it’s important you be absolutely sure before claiming you’ve detected something, lest everybody loses credibility.”

Such caution is well merited, because over the years astronomers have been wrong-footed by anomalous discoveries.

In the 1960s, a respected Dutch astronomer made headlines by claiming to have found wobbles in the position of a star consistent with an orbiting planet – the first beyond the Solar System.

It later emerged that the wobbles were nothing more than a shaky telescope mounting.

A few years later, radio astronomers at Cambridge detected regular radio pulses coming from deep space.

After naming it LGM-1 (Little Green Man 1), the team found they’d actually discovered the first pulsar, a rapidly spinning collapsed star emitting radio waves like a celestial lighthouse.

In May this year, scientists solved the 17-year-old mystery of so-called peryton signals, detected by a giant radio telescope in Australia. The source was the microwave oven in the observatory kitchen.

The smart money is on the strange behaviour of KIC 8462852 being the result of something less exotic than alien structures.

Even so, it’s hard not to hope that when the next dip occurs, astronomers find the best explanation is the presence of an orbiting black monolith.

Robert Matthews is visiting professor of science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK