It has taken a nine-year journey of 4.5 billion kilometres across the frigid void of space. But this month, astronomers will finally get what they have waited decades to see: the first close-up images of Pluto.

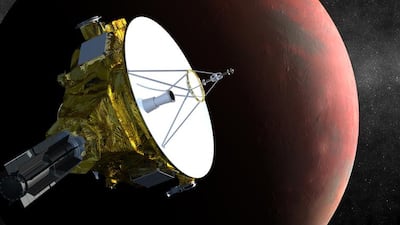

Since its launch in 2006, Nasa's New Horizons probe has been speeding towards its target at more than 50,000kph.

Now it is preparing to zip within just 14,000km of Pluto, its flight controllers achieving the equivalent of scoring a hole-in-one at Abu Dhabi Golf Club after teeing off from the Al Wathba Camel Race Track 30km away.

Even travelling at the speed of light, 300,000km a second, the images from the piano-sized probe will take more than four hours to reach Earth.

What they will show is anyone’s guess, for since its discovery in 1930, Pluto has remained a cold, dark enigma. Its colossal distance and small size – less even than our own Moon – have defied attempts by astronomers to find out anything but the most basic facts about it.

Even so, just months after the launch of New Horizons, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) decided it knew enough to demote Pluto to the official status of dwarf planet.

It was a decision that continues to cause controversy, not least among the New Horizons team. When they first mooted the mission more than 25 years ago, they could boast of completing the grand survey of the planets started in the early 1960s, when United States and Soviet probes first reached Venus and Mars. The IAU's decision meant the grand survey had already been completed in 1989, when Nasa's Voyager 2 flew past Neptune, officially the outermost of the Sun's family of planets.

But some astronomers now think the textbooks may have to be rewritten again, because there is increasing belief that there is a new planet lying far beyond even Pluto.

The notion of an as-yet undiscovered Planet X at least as large as the Earth emerged more than a century ago, with claims of tiny wobbles in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune, first observed by 19th century astronomers.

These hinted at the existence of a giant unseen world whose gravity was pulling the known planets off course.

It was the search for this planet that led to the discovery of Pluto by a 24-year-old American astronomer named Clyde Tombaugh – some of whose ashes are aboard New Horizons.

Observations of the new planet showed, however, that Pluto was far too small to account for the wobbles – and the quest for Planet X started anew.

Then in 1989 it was dealt an apparently fatal blow by the fly-by of Neptune by Voyager 2.

Its precision measurements of the planet’s mass and orbit showed that the wobbles that had intrigued astronomers for so long were an illusion. Planet X was suddenly redundant.

But now it is back once more, following the discovery of strange anomalies in the orbits of objects far beyond Pluto. First identified in the 1990s, these chunks of ice and rock are known as Kuiper Belt Objects (Kbos). Their origin is not clear but they are thought to be debris from the formation of the planets about 4.5 billion years ago.

Hundreds have been found on orbits beyond that of Neptune, with Pluto itself now thought to be a Kbo. But some follow far bigger orbits, with one – code-named 2012 VP113 – travelling out to a staggering 67 billion km from the Sun, almost 10 times the distance of Pluto. By charting the paths of these deep-space voyagers, astronomers have noticed about a dozen are on orbits with similar characteristics – as if some force is corralling them.

Now teams of researchers in the US and Europe believe the most plausible explanation is that Planet X really does exist but lies farther away than anyone previously thought.

Those making the case for Planet X include Dr Chadwick Trujillo and Dr Scott Sheppard, the American astronomers who discovered 2012 VP113.

Using computer simulations, they have shown that the strange alignments can be explained by a planet with a mass greater than that of Earth and orbiting 250 times farther from the Sun.

Researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid and the University of Cambridge have gone further, arguing that at least two Planet Xs are needed to explain the alignments.

Given the track record of claims for Planet X, there is bound to be scepticism. One obvious criticism is that it is based on studies of just a dozen or so Kbos following extreme orbits.

The dangers of pushing such evidence for Planet X too far were highlighted some years ago when astronomers noted a lack of Kbos on orbits much beyond that of Pluto.

This led to speculation that they were being swept out by the gravity of an unseen Planet X. Computer simulations suggested the culprit could be a Mars-like body lurking about 40 times farther from the Sun than the Red Planet.

Since then, however, dozens of Kbos have since been found in the “forbidden zone”.

As yet more are found, it is possible that the alignment effect will also prove illusory.

Then there is the mystery of how so vast a planet could end up so far from its parent star.

Until recently, astronomers thought solar systems were the result of the gravitational collapse of dust and gas clouds around young stars. The resulting planets then stayed pretty much where they were for billions of years.

But new models based on computer simulations suggest the gravitational tug-of-war can lead to massive upheaval, with some planets moving closer to the Sun while others are ejected.

In the end, the problem with all computer models is that even the most sophisticated are prey to Gigo: garbage in, garbage out. If astronomers unwittingly feed in faulty or incomplete data, their computers will still produce answers – but they too will end up faulty or incomplete.

There is still no substitute for going out into the wild and reporting back on what is out there. And that is what the New Horizons probe is about to do.

Robert Matthews is visiting reader in science at Aston University, Birmingham