In a few horrible hours, Pompeii was turned from a vibrant city into an ash-embalmed wasteland, smothered by a furious volcanic eruption in AD 79.

Then in this century, the excavated Roman city appeared alarmingly close to a second death, assailed by decades of neglect, mismanagement and scant systematic maintenance of the heavily visited ruins. The 2010 collapse of a hall where gladiators trained nearly cost Pompeii its coveted Unesco World Heritage Site designation.

But these days, Pompeii is experiencing the makings of a rebirth.

Revelations and new discoveries

Excavations undertaken as part of engineering stabilisation strategies to prevent new collapses are yielding a raft of revelations about the everyday lives of Pompeii's residents, as the lens of social class analysis is increasingly applied to new discoveries.

Under the archaeological park's new German-born director, innovative technology is helping restore some of Pompeii's nearly obliterated glories and limit the effects of a new threat — climate change.

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, 41, an archaeologist appointed director general 10 months ago, likens Pompeii's rapid deterioration, starting in the 1970s, to "an airplane going down to the ground and really risking breaking" apart.

The Great Pompeii Project, an infusion of about €105 million ($120m) in European Union funds — on condition it be spent promptly and effectively by 2016 — helped spare the ruins from further degradation.

“It was all spent and spent well,” Zuchtriegel said in an interview on a terrace with Pompeii's open-air Great Theater as a backdrop.

But with future conservation problems inevitable for building remains first excavated 250 years ago, new technology is crucial "in this kind of battle against time," he said.

Challenges facing Pompeii

Climate extremes, including increasingly intensive rainfall and spells of baking heat, could threaten Pompeii.

“Some conditions are changing and we can already measure this,” said Zuchtriegel.

Relying on human eyes to discern signs of climate-caused deterioration on mosaic floors and frescoed walls in about 10,000 excavated rooms of villas, workshops and humble homes would be impossible. So, artificial intelligence and drones will provide data and images in real time.

Experts will be alerted to "take a closer look and eventually intervene before things happen, before we get back to this situation where buildings are collapsing,” Zuchtriegel said.

Since last year, AI and robots are tackling what otherwise would be impossible tasks — reassembling frescoes that have crumbled into the tiniest of fragments. Among the goals is reconstructing the frescoed ceiling of the House of the Painters at Work, shattered by Allied bombing during the Second World War.

Robots will also help repair fresco damage in the Schola Armaturarum — the gladiators' barracks — once symbolising Pompeii's modern-day deterioration and now celebrated as evidence of its revival. The weight of tons of unexcavated sections of the city pressing against excavated ruins, combined with rainfall accumulation and poor drainage, prompted the structure's collapse.

The great uncovering

Seventeen of Pompeii's 66 hectares remain unexcavated, buried deep under lava stone. A long-running debate revolves on whether they should stay there.

At the start of the 19th century, the approach was “let's ... excavate all of Pompeii,” Zuchtriegel said.

But in the decades before the Great Pompeii Project, “there was something like a moratorium — because we have so many problems we won't excavate any more,” Zuchtriegel said. “And it was almost like, psychologically speaking, a depression.”

His Italian predecessor, Massimo Osanna, took a different approach: targeted digs during stabilisation measures aimed at preventing further collapses.

“But it was a different kind of excavation. It was part of a larger approach where we have the combination of protection, research and accessibility,” Zuchtriegel said.

After the gladiator hall's collapse, engineers and landscapers created gradual slopes out of the land fronting excavated ruins with netting keeping the newly-shaped “hillsides” from crumbling.

Near the end of Via del Vesuvio, one of Pompeii's stone-paved streets, work in 2018 revealed an upscale domus, or home, with a bedroom wall decorated with a small, sensual fresco depicting the Roman god Jupiter disguised as a swan and impregnating Leda, the mythical queen of Sparta and mother of Helen of Troy.

But if visitors stand on tiptoe to look past the marvellous fresco over the home's jagged walls, they'll see how the back rooms remain embedded under the newly “stabilised” unexcavated edge of Pompeii.

Nearby is the most crowd-pleasing discovery to emerge from the shoring-up project — a corner "thermopolium" with a countertop setup similar to the familiar salad-and-soup bar arrangements of our times.

This fast-food locale is the only one discovered with frescoes in vivid hues of mustard-yellow and the omnipresent Pompeii red decorating the counter's base — apparently advertising the chef's specialties and including a bawdy graffito. Judging by the organic remains found in containers, the menu featured concoctions with ingredients such as fish, snails and goat meat.

Quick street meals were likely a mainstay of the vast majority of Pompeiians not affluent enough to have kitchens.

Archaeologists have been increasingly using social-class and gender analyses to help interpret the past.

When they explored an ancient villa on Pompeii's outskirts, a 16-square-metre room emerged. It had doubled as the villa's storeroom and the sleeping quarters for a family of enslaved people. Crammed into the room were three beds, fashioned from cord and wood. Judging by the dimensions, a shorter bed was that of a child.

When the discovery was announced last year, Zuchtriegel described it as a “window on the precarious reality of people who rarely appeared in historical sources” about Pompeii.

Will Pompeii welcome the public?

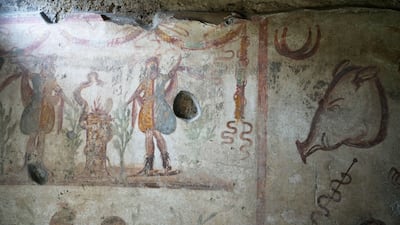

This winter, an afternoon guided tour is offered at sites not otherwise open to the public. One such offering is the House of the Little Pig. On a wall of a tiny kitchen is a whimsical painted design of a pig's head with a prominent snout.

The park's ambitions stretch further: nearby Naples and its sprawling suburbs ringing Vesuvius suffer from organised crime and high youth unemployment, which drives many young people to emigrate.

So the archaeological park is bringing together students from the area's more elite institutions and from working class neighbourhoods who attend trade schools to perform a classical Greek play at the Great Theater.

“We ... can try to contribute to a change,” Zuchtriegel said.

There are also plans to create public strolling grounds in an unexcavated section of ancient Pompeii which, until recently, had been used as an illegal dump and even a marijuana farm