"History is the version of past events that people have decided to agree upon” is a quote attributed to Napoleon Bonaparte.

Interestingly, Napoleon’s own story has not been “agreed upon”. It has been told and retold differently by different experts over the years, with new books and films about him still coming out – giving us an example of how people can’t really agree on history and its prominent figures.

If we focus on this region, there are some historical figures – those of pre-Islamic and early Islamic times – who are viewed as heroes and others as villains. Their stories are immortalised in prose, poems and drawings. But how much of it is fact and how much is fiction is open for debate.

Then there are some more recent events that changed the map of the Middle East, and other incidents that had rippling effects well beyond the region.

This part of our history is more complicated and often not agreed upon by a majority.

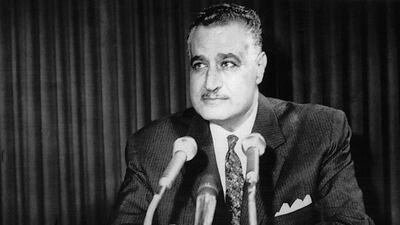

For example, mention the late Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser to a room full of Arabs of different ages and nationalities, and you’ll hear conflicting views on him and his legacy. It could become quite a heated debate, involving those professing great love for the pan-Arab leader to those vehemently accusing him of being the cause of everything terrible that ever happened.

We are all biased in some ways, shaped by the beliefs we have, the places we were raised in, and the events we have lived through.

The fact that we don’t have a unified or even a trusted source of our own history – relying, instead on others to write it for us – was highlighted this week via social media posts featuring a series of pictures taken of a Grade 9 history book taught at some English-speaking schools in the Middle East, including one in Dubai.

It labelled Palestinians as terrorists and said that they “claim” Palestine is their land.

After it went viral online and parents complained, the book was pulled from the curriculum. The fact that a book like that even made it through to classrooms, and was being taught to Arabs in the Arab world, is quite telling. It reveals how important it is for there to be unified, verified and well-researched history books about this region.

What are we teaching our children about our modern history? Do adults even know the facts?

Those who have lived through the events of the recent past have their own take on things, and they pass on their experiences to their children.

Having been in some Middle Eastern war zones, I can tell you that it is difficult to give a straightforward, simple version of some of the major incidents. It is even harder in some places to publish balanced, informative pieces because there is always the worry of a backlash from a powerful source or party somewhere. Every news outlet has its own mandate and limits. So anyone who wants to get a clearer, fuller picture of the past needs to consult all sorts of media. The truth, hopefully, is somewhere in the middle.

History books are written by those who won in the end; those who held on to power long enough to tell the story as they liked. So history books are facts peppered with fiction and biases.

At the same time, the minute someone with an Arab-sounding name publishes an article or book about this region, there are question marks added to it by readers – often other Arabs who wonder about the writer’s biases. There is, unfortunately, always the fear of a backlash.

The other day, a child asked me a very simple question: “So, what happened to Syria?”

I had no simple answer. The Syrian story is still unfolding. It is filled with conspiracy theories and unreliable accounts, and the names of its heroes and villains are still changing. Perhaps the only agreed upon enemy is ISIL.

If Arabs want their history to be told truthfully, they need to start telling it themselves in a more truthful and balanced way. There are some who are already doing this, and we need to support them, not attack them for taking a hard look at history.

rghazal@thenational.ae

On Twitter: @Arabianmau