Years ago, I was in a hotel restaurant in Samarkand, Uzbekistan – I was there in the middle of a long trek though Central Asia – and I was talking to a few of the locals. When you travel alone, I’ve found, striking up a conversation with strangers is easy.

When I say I “talked” to them, I’m perhaps overstating it. I don’t speak Uzbek or much Russian, and they certainly didn’t speak much English. But given enough cups of tea and the right attitude, I’ve found, people can make themselves understood.

We talked politics and religion and world affairs. We talked about cars and American basketball and what New York City is really like. And at some point, as I was trying to describe the beaches of Southern California, I suddenly realised that no one was listening to me. My new friends were all distracted, staring at the television in the restaurant with slack-jawed intensity.

The men were transfixed by a music video – it was years ago, as I said, and they were dumbstruck by the sight of the now-passé boy band, the Backstreet Boys, singing their hit I Want it That Way. For those of you who insist on pretending that you don’t remember it, here’s a short refresher: the Boys are dancing around, surrounded by screaming and fainting girls, and in the background is an enormous airplane – it looked like an Airbus A340 – with “Backstreet Boys” emblazoned on the side.

My new friends from Samarkand looked at the screen, then back to me, then back to the screen – and I could tell what they were thinking: “In the West, you all live like that, right?”

I shrugged as if to say: “Yeah, pretty much.”

Who am I, when you really think about it, to squash someone else’s dreams? Better they all figure out a way to come to the United States themselves and learn first-hand that we don’t all live like the Backstreet Boys. (And in fact, as emerged in the years after their break-up, it turns out that the Backstreet Boys didn’t even live like the Backstreet Boys.)

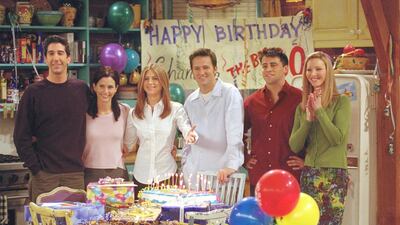

The power of those images, though – coupled with the universal, always-on, satellite-connected television – was probably a more effective piece of national propaganda than any government could ever devise. I spend about half the year living in New York City, in the area known as Greenwich Village, and it always amazes me to see tourists from all over the world clutching maps and guidebooks as they make their way to the apartment building where the characters from the hit sitcom Friends were supposed to live.

Friends, as everyone knows, may have taken place in New York City, but it was filmed entirely on a soundstage on the Warner Brothers Studio lot in Burbank, California. Before the show premièred, a film crew drove around Greenwich Village picking buildings and landmarks to film in order to have something to show – we call it an “establishing shot” – at the start of every scene. There really is zero connection between those shots and the television show – I mean, it’s not as if any of the stars ever set foot in that apartment building – but that doesn’t stop the tourists and curious fans from taking selfies in front of the building. The magnetic power of Friends or the Backstreet Boys is powerful indeed.

So powerful that groups of escapees from North Korea, now living and working in safety in South Korea, are busily smuggling movies, music videos and – yes – even episodes of Friends back into North Korea. It’s all described in the latest issue of Wired magazine, in a riveting article by Andy Greenberg.

The theory is, the benighted citizens of the Hermit Kingdom living under the brutal dictatorship of the Kim dynasty have been cut off from the western world for over half a century. All they know about the West is what they’ve heard from official government propaganda – that it’s a cesspool of warmongering, violence, greed and misery.

It’s some of those things, of course, but groups like the North Korea Strategy Center – founded by a former inmate of a North Korean re-education camp – are busily putting big-budget movies (Titanic is a favourite), documentaries and sitcom episodes onto tiny USB drives, bribing border guards and customs officials to get them into the most sealed-off country in the world, all in order to show the citizens of North Korea another side to the story.

There are now furtive groups of North Korean citizens watching Hollywood movies and television – a crime punishable by death, by the way – and learning that their leaders have lied to them. They’re discovering, USB stick by USB stick, that the West isn’t such a bad place after all, that if you can carry a tune with any competence someone will buy you an Airbus A340, and that there are enormous apartments available in Greenwich Village that even young, broke kids who spend all day lingering in coffee shops can afford.

We’ll know for sure that freedom has come to North Korea when there are tourists from Pyongyang wandering around my neighbourhood in New York looking for the apartment from Friends. And we’ll know that their world is a much better place when they’re disappointed by reality, just like the rest of us.

Rob Long is a writer and producer based in Los Angeles

On Twitter: @rcbl