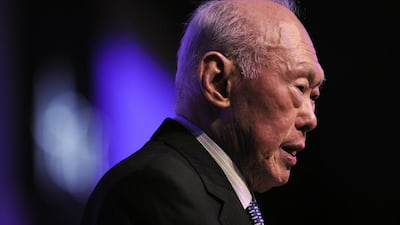

Some years ago I reviewed the third in a curious series of books called Giants of Asia for this newspaper. The interviewing style of the author, US academic Tom Plate, was certainly unusual, by being unremittingly sycophantic. But he was right about the status of his subjects, former leaders of East Asian states. They were indeed “giants”, and none more so than Lee Kuan Yew, Singapore’s founding father.

It has been necessary this past week to contemplate life without Mr Lee, as he has been on life support in hospital (his death was also erroneously reported). And it has been hard.

Mr Lee was one of the very last of the post-independence leaders whose dominant personalities transcended the countries they ruled. One thinks of the “big men” of Africa – Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia or Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya. In Asia, Indonesia’s Sukarno, Ne Win in Burma (as it still was during his time) and Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines come to mind.

But Lee Kuan Yew differed from them in two crucial aspects. First, he outlasted them in office and in life. Mr Lee led Singapore as prime minister from 1959 to 1990, and went on to play an influential role as senior minister (1990-2004) under his successor, Goh Chok Tong, and then minister mentor (2004-2011) under the state’s third premier, his son Lee Hsieng Loong.

Second, he was prodigiously successful, which most of his contemporaries were not. Too many came to power as nationalist independence heroes, fully committed to socialism and the ballot box, but within a few years had managed to become “presidents for life”, while their friends and family had accumulated assets not entirely consistent with their professions of left wing beliefs. Their economies, sadly, also too often ended up ruined, while a plutocratic elite still found the dollars for Cadillacs, mansions and expensive western educations for their children.

Mr Lee, on the other hand, unlike those leaders who trumpeted the virtues of democracy while mysteriously winning around 99 per cent in the polls, long made his contempt for one man, one vote clear.

There have always been parliamentary elections in Singapore, but Mr Lee made his doubts plain about the whole system, declaring in a 1990 speech: “With few exceptions, democracy has not brought good government to new developing countries ... westerners value the freedoms and liberties of the individual. As an Asian of Chinese cultural background, my values are for a government which is honest, effective and efficient.”

The great difference with Lee Kuan Yew was that he was astonishingly successful. This, despite the fact that he became a national leader by mishap, or certainly not by his own intention. British rule ended in Singapore when it joined with the already independent Federation of Malaya and the North Borneo states of Sarawak and Sabah in 1963. Two years later, Singapore had been kicked out of Malaysia, and the circumstances were not propitious.

The economy, wrote Mr Lee in his autobiography, was one of his biggest headaches. “We had to make extraordinary efforts to become a tightly knit, rugged and adaptable people who could do things better and cheaper than our neighbours, because they wanted to bypass us.”

What he managed to achieve in Singapore is justly reflected in the title of the second volume of his memoirs: From Third World to First.

Mr Lee’s Singapore was always business-friendly and pragmatic, and he has been consistently unapologetic about the constraints on individual liberty and free speech he considered necessary for the country to progress. Questioned by a BBC reporter about the infamous ban on chewing gum, he replied: “If you can’t think because you can’t chew, try a banana.”

For those brave enough to come out as opponents, life has not been comfortable. And a Singaporean joke concerning an engineer named Lingam suggests that the populace is well aware of the pact they have apparently made over freedom versus development.

Lingam, so the joke goes, applies to move to Malaysia permanently. The Singaporean cabinet is shocked and sets up a task force to investigate. They ask him a series of questions: Why does he want to leave? Does he have any complaints about his job, his salary, his housing, or his children’s schooling?

“No,” Lingam says. “I have no complaints.”

So why, they ask, is he migrating to Malaysia?

“Ah,” he replies, “there I can complain.”

Fair enough. But to older generations of Singaporeans, the transformation they have witnessed conquers all. “If you knew what the country was like when we became independent,” is a familiar refrain. Few will hear anything said against Mr Lee.

Singapore is changing. Mr Lee himself has predicted a time when his ruling PAP will not be in power and the country may well loosen up eventually in all sorts of ways, including allowing the unfettered chewing of gum (although one may well ask what kind of advance that would constitute). But his place in history is assured.

Many others of his era eschewed democracy and tried to become Platonic benevolent despots, but their despotism always ended up exceeding their benevolence and their economic plans ended as dust. Lee Kuan Yew was unique in combining both qualities. If I say we will not see his like again, some may be glad – but modern Singapore is his legacy, his epitaph. I suspect that will suffice.

Sholto Byrnes is a senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia