The roll call of countries where it is right to claim ISIS never went away has steadily expanded in recent months.

That is certainly underlined by the Pentagon’s action over the weekend to launch a wave of air strikes on the group across Syria. It was also patently clear in the deadly attacks in Manchester and Sydney this year, where ISIS-inspired gunmen pledged their loyalty as they struck.

In January 2024, the group’s propaganda channels used the aftermath of the Hamas-led attacks inside Israel on October 7, 2023 and the subsequent outbreak of war in Gaza to instruct loyalists to kill Jews wherever they can find them. Investigators reportedly believe this was instrumental to both deadly assaults. And to followers of the news in Africa where ISIS loyalists are besieging important capitals, there is little doubt of the resurgence of its influence as a major local power.

It has been clear for a decade and a half that ISIS works along existing fault lines to boost its pulling power. While it has several modes of operation, which I will go into below, it has a single starting point. It wants to pull people into pledging their loyalty to it, carrying its goals to the places where they are based. This is why it is important to recognise that the growth of ISIS is also a creature of the news. The exploitation of the harms and injustices – as received by its audience – is central to the group’s playbook.

A decade ago, European cities in France and Belgium bore the brunt of one phase of the ISIS era that has hallmarks of what is happening today. The faultline that ISIS sought out was centred on laying down differences in lifestyles that could become divisive issues. By spreading horror and fear, the group’s attackers could force open divisions in society. That has continued around Europe ever since. Last year, the Taylor Swift tour became a target for a plot that had the same objectives.

What is now established is that ISIS can rely on a western archetype to power its presence in this sphere of violence. There is a certain type of man who is either rootless or unsettled in early adulthood, with no real job or career path and with a predilection for video gaming and a probable obsession with weight training.

Tapping into their personal heritage allows these recruits to work their way through the fanaticism on offer from ISIS and its propaganda channels. What it offers is a break from the narratives of their upbringing and the societies their parents had spent their time adjusting to. That process of adjustment had usually been a struggle for the parents, and for too many of the ISIS-vulnerable offspring, something has short-fused in the process.

Once the European terror attacks became an established pattern, it allowed the ISIS propaganda machinery to hone into the theme. The wave of migration that landed in Europe around the same time has seen new arrivals – also dedicated to the gym and the screen – turn their frustrations into nihilistic plotting as well.

When the Englishman John Cantlie was one of the faces of ISIS propaganda more than a decade ago, it was clear how the group wanted to project its appeal beyond the strictly territorial. For the most part, as the group was driven out of cities and towns across Iraq and then Syria, it maintained the kernel of its propaganda infrastructure. Video pledges of loyalty by attackers show that their schemes of retribution or self-described revenge have been formed in the stream of that output.

Platforming ISIS has been an issue that the social media world has never properly got to grips with, and that has been a factor in how it has endured. AI is set to transform its propaganda, shedding the weekly rhythm of its messaging, extending the scope of its output and pumping up the volume at which it distributes its content. Lobbying for guardrails is urgent, but this seems destined to be neglected in too many places.

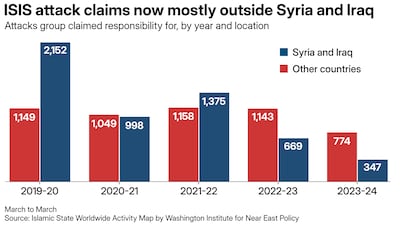

Once the ISIS footprint in the Levant – which at the group’s height was about the size of Portugal – had gone, there were many who turned the page on the threat. Conditioned to think in terms of territory and national boundaries, the military fight was devolved almost down to commander-level concerns about remnant activity or reconditioning of places that were won back.

It was at the former overlords of these territories that the Pentagon strikes were aimed. After the deaths of three US personnel stationed in Syria, US Secretary of Defence Pete Hegseth reached for words that were Maga-branded projections of force. “This is not the beginning of a war – it is a declaration of vengeance,” he said.

That marker is duly laid down and Washington is signalling its interest in containing ISIS these days. But the swelling multi-dimensional rise of ISIS will not be contained by bombing campaigns alone. It is worth noting that Al Qaeda is separately in expansion mode, most notably in Yemen and in parts of Africa. ISIS is also facing a new reality with different powers running Syria and Afghanistan. How Washington works out ways to play a role not only with long-standing partners like Iraq but new dispensations in other key countries is hugely important to what happens with ISIS.

The multi-dimensional challenge that ISIS presents is not easily summarised because its operations work at many different levels. What is needed is fresh focus on how to blunt its growth and making a start on chipping away its resilience across all its stripes.