This week, the United Nations human rights chief, Zeid Raad Al Hussein, called for the world to reject populist bigots. He’s right to have done so. Whether in the West at the hands of demagogues such as Donald Trump and Geert Wilders or in the Arab world with sectarian radical extremists, such chauvinism is only a stain on our societies. But concern about such jingoism can also be abused – which appears to have happened with a recent British delegation that met Syrian president Bashar Al Assad in Damascus.

Since the Syrian uprising began in 2011, the Assad regime has promoted itself as a protector of pluralism and defender against sectarianism. In particular, it has described itself as upholding the rights of minorities, especially Christians – a population that Mr Al Assad knows is of particular concern to co-religionists in the West.

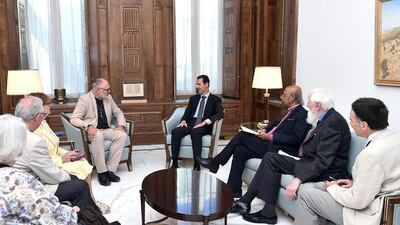

It is against that backdrop that a small group of British figures, mostly members of the House of Lords and Christian clerics, visited Damascus. They have yet to explain the reasons for their trip, which was made public by the Syrian regime’s media outlets before the Britons had declared anything themselves. But the symbolism has already been noted – and used. Irrespective of the good intentions any of the delegation members might have had, the regime has used the trip as a propaganda tool to bolster its legitimacy at home and abroad.

The group included Lords cross-bencher Baroness Cox and Anglican bishop Michael Nazir-Ali. Both are known for having concerns about the persecution of Christian minorities in different countries, but that does not necessarily translate into concern for minorities more generally.

Baroness Cox has the dubious honour of having invited Geert Wilders, one of the most vocal anti-Muslim bigots in Europe, to speak at the House of Lords – a disgraceful act at the heart of British democracy. To compound the issue, she issued the invitation in association with UKIP, a party that has been harshly criticised by mainstream political forces for its intolerance and prejudice. This is hardly evidence of concern for minorities.

This type of inconsistency is not only something that characterises certain members of the British delegation to Damascus, rather it is a distinguishing feature of Mr Al Assad’s regime. For all of his pontification about respect for pluralism and abhorrence of sectarianism, Mr Al Assad and his regime have not been opposed to sectarianism when it suits their interests.

In pushing back the Syrian revolutionary uprising, Mr Al Assad has allowed for a deep sectarianism to unfold. By allowing foreign Shiite fighters – including those from Iraq and the Indian subcontinent, and members of the Lebanese movement Hizbollah – into Syria, he has pitted Shiites against Sunnis. The sectarianisation of the conflict is something that Mr Al Assad’s regime enables.

The regime certainly does not penalise Christians for their worship or religious identity in the same way that ISIL or extremist Islamists do, but this pluralism is only skin-deep. One need only ask if political pluralism is permitted under Mr Al Assad’s system of governance.

Some might argue that engagement with Mr Al Assad has to take place if we are to find a political solution to the tragedy in Syria. Even if one accepts that, the British delegation remains wholly inappropriate. It contained no one who was in the slightest way empowered to negotiate on behalf of the United Kingdom. Although some were members of the House of Lords, they have no political authority nor are they elected. If the delegation was meant to have symbolic multi-faith or multi-religious authority of any kind, then it again failed in its composition, which was wholly Christian and very poignantly so. The delegation could only be described in association with one word: appeasement.

There are genuine concerns about the fate of Christian communities in Syria, the Arab world and more generally worldwide. But the concern for such communities cannot be separated from concerns about freedom and liberty for all. Mr Al Assad’s regime is responsible for the deaths of many times more Syrians than the extremists that this delegation appeared to be concerned about.

The freedom of Christian Syrians and other communities of Christian Arabs cannot be separated from the freedom of everybody in the region. Pursuing their rights is unlikely to prove sustainable by appealing to dictatorial regimes and becoming part of their propaganda. Rather, the freedom of Christians in the Arab world, and the freedom of others in the Arab world, remains intertwined – and their futures remain one.

Dr HA Hellyer is a senior non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council in Washington and the Royal United Services Institute in London

On Twitter: @hahellyer