Who would benefit most if peace came to Afghanistan after decades of war and instability? First of all, the suffering people of that country. But not far behind would be China, one of whose key strategic impulses is the economic penetration of countries to its west. China is spending billions of dollars on funding railways to link landlocked Central Asian countries – including Kazakhstan and Afghanistan – to Europe and the Far East.

This new Silk Road is primarily about access to markets, enabling manufacturers in China’s underdeveloped west to send goods by rail to Europe and providing China with easy access to reserves of mineral wealth, from oil to copper. But geopolitics is never absent from these plans. A land link by rail to Europe and through Pakistan to the shores of the Gulf provides an alternative to the shipping route through the Strait of Malacca, a choke point for China’s seaborne trade and one that is always susceptible to being blocked by the US navy.

China’s first steps towards promoting a peace agreement in Afghanistan should be understood against this backdrop. It has just emerged that a delegation of Taliban leaders visited Beijing in November to discuss China’s plan for an Afghan “peace and reconciliation forum”. This has been at the urging of the new president, Ashraf Ghani, who is keen to engage China both as a mediator and as a potential backer.

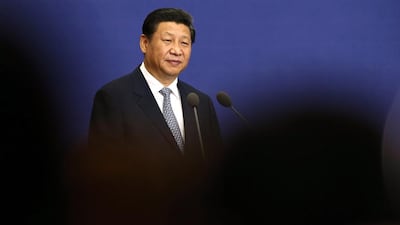

Mr Ghani is hoping that China will use its influence with Pakistan to persuade the Taliban to take the peace process seriously, even if at the moment it is no more than a number of forums of regional powers. There are plenty of reasons to hope that China will take the unprecedented step of seeking to resolve a conflict beyond its borders. China’s global ambitions have moved up a notch under Xi Jinping, in line with predictions that its economy will overtake that of the United States soon. In November, Mr Xi spoke of “great power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics”. This is a long way from Deng Xiaoping’s self-effacing nostrum: “Hide one’s talents, bide one’s time and seek concrete achievements”.

Even if the US is not quitting Afghanistan entirely, it is seen in the region as a declining power. Any chance of regional agreement under US leadership is undermined by the mutual suspicion between Iran and America. Any agreement between Mr Ghani and the Taliban would have to be endorsed by all Afghanistan’s neighbours. The big question is how much China is willing to risk. In other words, what does “great power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics” mean, given that Mao Zedong said that the Chinese should never pursue self-serving great power policies.

Bringing peace to Afghanistan is hardly self-serving, and economic development in Afghanistan would be a boon to the whole region, even if China would be the major beneficiary. China has an undoubted interest in curbing militants from its restive 10 million strong Uighur minority in Xinjiang province, who are holed up in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region. A series of explosions and knife attacks has been blamed by Beijing on Uighur separatists.

But the potential rewards of attaining these goals may be outweighed by the risks of trying to resolve a conflict abroad.

How could China achieve a goal that has eluded the great imperial powers – Britain, Russia and the US?

The neutral image that China currently enjoys could speedily evaporate once it is seen to be backing one side or the other, or pursuing its own commercial interests.

So far China has said it will only be a facilitator for a peace process set up by Mr Ghani. China’s only interest is as a “victim of terrorism”, Sun Yuxi, special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, told the BBC in December.

It is true that China sent no troops to Afghanistan during the US-led war, and so emerges without the taint of having been part of the army of occupation since 2001. But it can hardly claim to be a disinterested party in the region and nor is it without historical baggage.

Its alliance with Pakistan, based on a common interest in curbing Indian power, is too important to be sacrificed for the sake of Afghanistan. Perhaps the best example of how China may behave is shown by its 30-year lease on the Mes Aynak copper mine in Logar Province. It was bought for $3 billion by a Chinese state-owned enterprise in 2007.

Work has still not yet begun on the mine, and the company is now trying to extricate itself from the contractual obligations to invest in local infrastructure. This may reflect the collapse in the price of copper, and the commercial imperative to keep the copper deposit out of the hands of rivals, but it has disappointed those who hoped that Beijing would shower the country with gold out of goodwill.

Clearly China is not going to wave a magic wand over the Afghan imbroglio. But it cannot escape playing a part in attempts to find a solution. Right now, there is the temptation for it to show that it can play a leading role.

Alan Philps is a commentator on global affairs

On Twitter: @aphilps