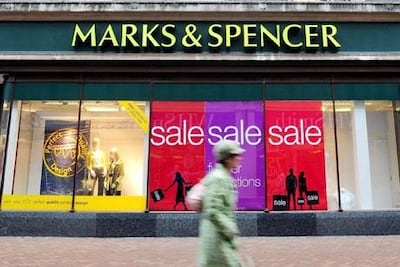

No company occupies such a place in the British psyche as Marks & Spencer.

The firm is part of the fabric of the country’s life, unique, at once familiar, to be pored over and examined and discussed. It doesn’t matter that the numbers visiting and spending at the chain’s branches are not what they were – “M&S”, as it is universally known, is a brand that has achieved the status of “national treasure”.

As with celebrities who are similarly and undefinably anointed – it just happens – this is a position of affection but not necessarily abiding success. It’s reserved for those we know and love, but not necessarily still in great demand, not how they used to be. In short, it’s for those whose best years are behind them.

Other retailers come close: John Lewis, but it’s not nationwide; Boots, in the past, possibly, but no longer; Tesco, hard to work up any emotion there. No, M&S is out on its own. As indeed it once was on the stock market. For years, M&S was hailed by the City as the bellwether – if the store group’s figures were strong, everything was well with the economy, consumers were happily spending.

That, however, seems like an age ago. Such has been the decline in the brand’s performance in the last few decades that M&S has lost that lustre. Today, it is Next that stock pickers look to for indicators as to the underlying health of UK Plc.

Over that period, as the rot set in, bosses came and went at an alarming rate. Each one of them would come up with a plan for turning the stranded, arthritic behemoth around, for enabling it to move forward again. Their every move would be hailed as the second coming, only for it to be quietly abandoned and then for the chief architect to go, as shoppers resolutely stayed away.

Now, though, I’m prepared to stick my neck out, and say M&S is better and sustained recovery could be finally happening. I’m not alone in that view: the shares are trading at a 17-month high. A recent trading update was a rarity for this company in recent years: catching the market by surprise with positive news. A 29.1 per cent year-on-year sales increase in the 19 weeks to August 14, and a profit forecast at the upper end of previous predictions of £300 million-£350m (tellingly, the first such upgrade this century) for once made investors want more, not less, of M&S.

It’s not only the figures, however, welcome as they are. For more than five years, M&S has had the same chief executive in Steve Rowe; for four years, Archie Norman has been chairman.

Having met them both, they’re a contrasting duo. Rowe, 54, is a corporate lifer. Even before that – his father, Joe, was head of food for M&S and a main board director. For all his pedigree, Rowe comes across as a fast-talking man of the people, intuitive, a natural merchandiser. There isn’t an M&S shop he doesn’t know – I mentioned my home town outlet, 300 miles from London, and he could describe it intimately.

Norman, 67, is different. He’s more urbane, studious, ex-McKinsey. But Norman is a rare creature, a management consultant that does not behave like one, a commercial strategist blessed with empathy. He proved that to startling effect when he ran Asda. Norman took over what was effectively a bankrupt organisation, financially and creatively, and transformed it – for seven successive years, Asda outperformed virtually all its rivals.

He did it by sweeping the old structures and ways. Nothing was sacred, little was spared. Norman recruited colleagues who were not only retailers but communicators, they had to be able to talk to those above and below, and to customers and suppliers. Offices were made open-plan, meetings were held standing up, rigid hierarchies were scrapped, surnames and titles were abolished, reserved parking spaces for managers were outlawed. Some of it seemed nutty – staff wore baseball caps to denote they were thinking and should not be disturbed – but overall, it more than worked.

Something similar may, just may, be occurring with M&S. Rowe and Norman are shutting swathes of laggard stores, no mean feat when closing one branch is met by howls of rage from local politicians and press, the chamber of commerce, not to mention still-loyal shoppers. The closure schedule is now in its high 10s, with other, predominantly clothing stores switching to offering more food. They’ve got the IT and logistics working; online has caught up (hard to think that for several years, while the competition was rushing into e-commerce, M&S stayed away and was not selling on the internet at all); management has been streamlined; costs have been taken out; a partnership with Ocado, the grocery delivery service, is producing; food is powering ahead.

The list of changes is staggering, and relentless. They’ve a title for the transformation: 'Never the Same Again'. At a corporation imbued with traditional methods and processes, that very name would once have been anathema. As it is, the revolutionary Never the Same Again is also aimed at fast-tracking change and ensuring M&S does not slip back into former habits.

Evidence of the new approach comes from the decision that more than half of the 254 bigger stores will no longer sell men’s suits. It’s replacing them with “smart separates” of chinos and shirts. Partly, this was brought about by the pandemic but the trend to more casual workwear was advanced before the virus hit.

The point here is that the previous M&S would have taken an age to make this step. It appears obvious but nothing was ever so straightforward, not where former managements were concerned. They would have soldiered on, filling their floors with racks of grey and dark suits that hardly anyone wanted. Those chieftains would not have been so bold as to chuck them out – the notion of a larger M&S not holding men’s suits would have been unthinkable, to those men, nearly always men, who ran the company and yes, wore suits.

Rowe and Norman, of course, are men. More credit to them, then, further proof that in Never the Same Again they’re practising what they preach.

Still, this has been greeted in some quarters as shocking, akin to a favoured actress suddenly altering her appearance. These would be the same critics who stopped going to M&S years ago but regard it as their right to complain and moan. Forget them, Rowe and Norman mean business, M&S means business, and it’s been a long time since anyone could state that with conviction.