To look forward in Syria, it is important to look back at the scale of damage left behind by the regime of former president Bashar Al Assad. For all the talk about huge investment pledges and rapid policy changes, the data shows the country is clawing its way along the long road to recovery.

People

The civil war raged for nearly 14 years and displaced more than 13 million people. At least 6.1 million Syrian refugees fled to live in Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan and beyond. Israel's attacks on Lebanon and the fall of the Assad regime in late 2024 led many people to return to Syria.

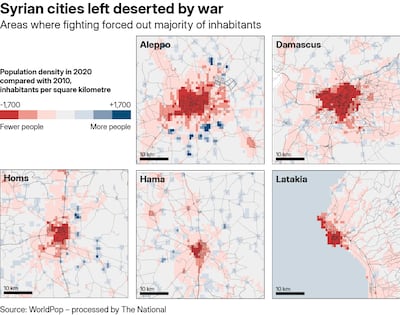

The intensity of strikes and fighting in cities such as Aleppo and Homs led to significant changes across the country; major urban areas became more sparsely populated. People were internally displaced, finding new homes in other parts of the country or creating new settlements on the periphery.

According to the UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), the number of internally displaced people reached its highest mark at 7.6 million in 2014, three years after the start of the war. The figure remains consistent with the current estimate of 7.4 million displaced people for 2025.

However, many who initially fled the violence seem to believe it is safe to return. Since the fall of Mr Al Assad, more than one million refugees have returned, the majority travelling to Damascus, Aleppo and Idlib.

Economy

Syria’s GDP fell by about 1.5 per cent in 2024, after more than a decade of contraction and brutal war. The World Bank forecasts it will grow by about 1 per cent this year, even with a change in leadership and the easing of western sanctions.

For more than a decade, Syria's trade balance was in deep deficit, highlighting the collapse of its infrastructure and manufacturing. Before the outbreak of civil war, agriculture-related manufacturing amounted to about 25 per cent of the country's GDP. Other notable exports included petroleum products, cement and construction materials, as well as textiles. More than a decade of war has devastated all of Syria's industries.

Compared with 2010, the economy has shrunk by about two-thirds. Estimates from various monitors reveal a 64 per cent contraction in GDP, with output dropping from more than $60 billion before the war to about $20 billion.

Rebuilding Syria after more than a decade of conflict is expected to cost $216 billion, the World Bank says. That is almost 10 times Syria’s 2024 GDP and emphasises the vast disparity between the scale of the destruction and the size of the economy.

Yet the government of President Ahmad Al Shara has quickly drawn significant regional support. Within a year, investment and business commitments have been announced with countries including Qatar, Turkey and Saudi Arabia.

The US has lifted long-standing sanctions, while the UK and EU have also eased most restrictions. Saudi Arabia and Qatar reportedly paid off Syria’s debt to the World Bank, valued at $15 million.

Cost of living and salaries

About 90 per cent of Syrians live in poverty, according to the UN, with about 25 per cent of the population in extreme poverty. Despite the new government's focus on the economy, a structure damaged by decades of corruption does not disappear overnight.

Mr Al Shara moved to counteract the "bribery economy" with two decrees in June 2025, mandating a 30 per cent increase in salaries for state employees and raising pensions for retired people by 200 per cent. However, this raises the question of how the country keeps up with inflation.

However, food prices have eased compared with 2023, when Syria experienced the worst of its bread crisis. At its peak, the average cost of a loaf reached about $1.53, up from $0.25 in 2011. With sanctions partially relaxed and imports resuming, basic goods are back on shop shelves, though affordability remains a significant issue.

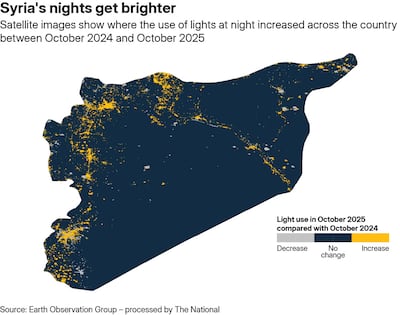

Fuel and lighting

One telling measure of national recovery is the use of light at night. During the war, fuel shortages and relentless destruction plunged large parts of the country into darkness. Since the downfall of the Assad regime, the government has moved quickly to restore electricity.

Analysis of satellite images by The National found that, among regions that showed a change in light use between October 2024 and October 2025, 77 per cent recorded an increase.

Fuel shortages had become so severe during the war, especially in winter, that the use of firewood surged. As a result, deforestation peaked in 2012 with an estimated 213 hectares of trees felled, especially in the coastal province of Latakia. Much of that was also driven by internal displacement, as more people fled fighting in cities such as Aleppo.

Safety and social cohesion

One of Mr Al Assad’s darkest legacies is the scale of death and disappearances. Estimates vary, but it is believed that more than 500,000 people were killed in Syria, most at the hands of regime security forces, the army and Russian and Iranian groups.

More than 100,000 are believed to have been tortured or executed, and another 100,000 remain missing. That is about one in every 70 Syrians. Mr Al Assad’s prison network was notorious, with thousands vanishing at detention centres. An Amnesty International investigation in 2017 reported that up to 13,000 people were hanged at Sednaya prison between 2011 and 2015.

Among the most horrifying atrocities committed by Mr Al Assad's regime was the 2013 sarin gas attack in the city of Ghouta, which killed more than 1,400 people. It was condemned as a war crime by the UN secretary general at the time, Ban Ki-moon.

Yet the fall of Mr Al Assad has not brought an end to violence. The new government has been accused of aiding or failing to prevent extrajudicial killings or attacks on minority groups, particularly in Sweida and Latakia, where Druze and Alawite communities faced violence, respectively.

Israel has also taken advantage of the transitional period, seizing more territory in the occupied Golan Heights and killing about 150 people in strikes and military operations in Syria.

Although the Assad regime is gone, the country has a long way to go to ensure its security and repair social fractures and ties between Damascus and minority groups.