Egypt’s government is proclaiming the end of an economic crisis that has plagued the country since 2022.

A strengthening Egyptian pound and falling inflation have been touted as evidence of recovery, but analysts say the picture is far more complex and that better times remain out of reach for millions financially.

Prime Minister Moustafa Madbouly declared last month that the “economic crisis is over,” saying Egypt would not seek further financing from the International Monetary Fund beyond a current $8 billion loan.

The Egyptian pound gained 5.25 per cent in value against the US dollar between January and September, while inflation – which had peaked above 35 per cent in early 2024 – is now at its lowest since early 2022.

That was when Russia invaded Ukraine, dealing a shock to the world economy and especially to countries such as Egypt that imported wheat from the war zone.

Moreover, Egypt's government has touted progress in reducing its debt-to-GDP ratio, which is projected to drop to 80 per cent by next year, down from a high of 97 per cent. Agricultural exports have also increased by more than half a million tonnes in a year.

Despite these claims of recovery, the overall picture is far murkier. Analysts argue that Egypt’s economic progress is fragile, with the government's reform programme falling short of its goals.

Mohamed Ragab, an economic analyst, told The National that while reforms have helped stabilise the economy after a financial crisis worsened by the Russia-Ukraine war, the country is effectively “back to where it was in 2016”.

That was when Egypt first turned to the IMF for assistance, with a promise to loosen state control over the economy and foster private-sector growth, objectives that have been routinely postponed until now.

While the government has made some progress, such as floating the Egyptian pound, the state's "overwhelming presence in the economy continues to repel many investors who value competitiveness”, Mr Ragab said. “A real recovery won’t start until the government steps back and allows the private sector to thrive.”

The IMF itself has expressed concern over Egypt’s slow progress on reforms. As part of a four-year $8 billion loan programme, it told Egypt to sell dozens of state and military-owned companies to attract foreign investment. However, little progress has been made and the IMF has withheld a fifth tranche of funding.

Despite the criticism, some signs of progress are undeniable. Egypt has recorded significant growth in exports, particularly in agriculture and in engineering products, where they rose by 15 per cent in the first half of this year.

Egypt's central bank has cut interest rates three times this year after maintaining a strict approach since the IMF deal began. Lending rates have dropped from 27.5 per cent to 22 per cent, making financing more affordable for businesses.

“These rate cuts have helped exporters by lowering borrowing costs, enabling them to grow production and compete more effectively in global markets,” Mr Ragab said.

However, central bank data suggests Egypt’s reliance on short-term debt instruments remains a concern. Public debt matures in just over a year and a half on average, only a slight increase on 2024.

Analysts also attribute part of Egypt’s recovery to external factors, particularly the weakening US dollar. This has strengthened the Egyptian pound and eased some pressure on the economy.

“I think the reality is that some of the recovery can be attributed to the government’s efforts and some of it is due to the dollar’s weakness,” Mr Ragab said. “The important thing now is for the government to build on this relative stability with more structural reforms to ensure a sustainable recovery.”

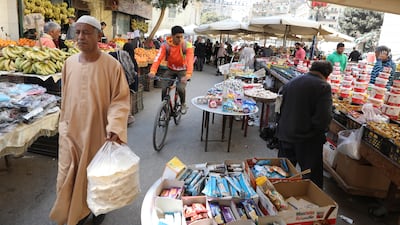

While the government celebrates its accomplishments, the average citizen has yet to feel the effects of the so-called recovery. Economic problems, which caused prices of basic goods doubled or tripled, still blight millions of Egyptians.

While inflation dropped to 12 per cent last month, prices for certain goods are still increasing, though at a lower rate than before.

“Essential goods are still far out of reach for most people,” Abdalla Nasef, a political analyst and host of the popular Tahrir Podcast, told The National. “The government’s declaration of victory does not reflect the reality on the ground, where citizens are struggling with stagnant wages and unaffordable prices.”

Mr Nasef argued that the government’s focus on macroeconomic indicators, such as the debt-to-GDP ratio and export growth, ignores the experience of ordinary Egyptians. He called for greater transparency, particularly regarding how the government is financing the so-called recovery.

“Citizens deserve clear answers about where the money is coming from, how it is being spent and who ultimately benefits,” Mr Nasef said. “So far, much of this recovery seems to rest on opaque deals, like the sale of state assets, raising questions about the sustainability of the government’s strategy.”

For millions of Egyptians, the economic crisis is far from over and the success of any recovery will ultimately depend on whether it improves their daily lives.