Lebanon and Israel are closer than ever to signing a deal demarcating their maritime border, opening the door to new oil and gas exploration, after years of US-brokered negotiations.

Both sides have said they are happy with the content of the plan. Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid said his country had reached a “historic deal” with Beirut. Lebanese President Michel Aoun said it "satisfies Lebanon" but stopped short of confirming the agreement.

The deal is set to ease security and economic concerns in both countries, whose shared history is rife with hostility.

It will resolve a territorial dispute in the eastern tip of the Mediterranean, but does not touch on their land borders, which have yet to be settled.

Lebanon and Israel, formally at war since 1948, have no diplomatic ties and have done little to formally agree on the border between their two countries.

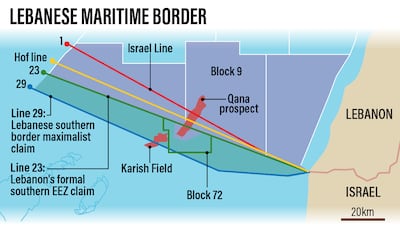

Both claim an approximately 860-square kilometre section of the Mediterranean Sea.

The impetus to agree on where the boundary between the countries stood became more important when Israel discovered and began to extract oil and gas in its waters.

Here's what you need to know.

What is the maritime border between Lebanon and Israel?

The border begins around a rocky cliff overlooking the Mediterranean where a UN peacekeeping force is headquartered.

Areas in Cyprus and Israel’s Exclusive Economic Zones, which border Lebanon’s waters, have proven to be rich in hydrocarbons.

This, along with some seismic assessments conducted by surveyors in Lebanese waters, has raised hopes that the country's seas will also yield significant quantities of oil and gas.

The maritime border agreement is aimed at demarcating each country's EEZ.

What about oil and gas exploration?

Israel has discovered huge deposits of natural gas in its EEZ that is used domestically and exported.

Lebanon has lagged behind. Although licences there were issued for two blocks, no production has happened and other blocks have yet to receive bids.

A sizeable discovery could help ease Lebanon's financial crisis, which has left the state unable to import fuel for its power plants.

But that is not necessarily the case, warn experts who also say that politicians should not pin solutions to today's crisis on a potential windfall from hydrocarbons down the road.

Exploration, they point out, is a long and prospective process. It is impossible to know when gas will be found and whether it will be abundant enough to warrant extraction.

"We cannot know how much a prospective field contains until we drill," Marc Ayoub, an energy researcher at Beirut's Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, told The National in August.

What are the two main energy fields in the disputed region?

There is one gasfield in a southern Lebanese exploration block, called Qana.

It is estimated to be small and has yet to be explored.

Israel said in recent weeks it wants to get a commercial share of royalties from the field as it extends into its waters.

Israeli officials have already met TotalEnergies to discuss a mechanism.

Lebanon's senior negotiator Elias Bou Saab said Lebanon had retained its rights with Qana and that Beirut would not pay "one cent" from its part of the field to Israel.

A second field, Karish, is already being developed under an Israeli licence farther south and is due to come online soon.

Israel said before it will keep the field, which is located below a maritime area known as Line 23, under its control.

Line 23 is the maritime line officially claimed by Lebanese negotiators.

However, complicating the matter is that in 2011 a group of Lebanese army specialists — backed by the UK Hydrographic Office — demarked an area to the south which they said should be Lebanon's boundary, named Line 29.

This would give Lebanon about 1,400 square kilometres more territory than Line 23.

Claiming Line 29 would put part of the Karish gasfield that Israel is planning to start exploiting inside Lebanese territory.

The momentum in negotiations comes against a backdrop of heightened tensions ― Iran-backed Hezbollah has threatened to attack Israel if it continues with its plan to extract gas from the field.

What is Lebanon's 'unified stance'?

Amos Hochstein, the Israeli-born US diplomat mediating between the two countries, has attributed the “positive” direction of the talks to the unified position adopted by Lebanon’s three leaders — President Michel Aoun, caretaker Prime Minister Najib Mikati and Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri ― whom he met last week.

The three men are from different political factions and previously had different red lines on any agreement.

The US made it a precondition to resuming the stalled talks that Lebanon agrees on a unified position regarding the negotiations. This essentially means that if negotiators finalise a deal with Israel, it will not then be blocked by a different part of the Lebanese state with its own demands.