In the last few moments before the sun drops behind one of its hills of giant boulders, something happens in the backpacker haven of Hampi. Silence descends on the top of Matanga Hill, where a handful of dreadlocked travellers and ordinary tourists have come to see out the day. They gaze out over the colonnades of a ruined bazaar below, over the pillars from a long-fallen bridge, over the remains of temples on nearby hilltops, and down onto the high tower of the Virupaksha temple, all of it surrounded by rice paddies and banana plantations and bathed in a gentle light.

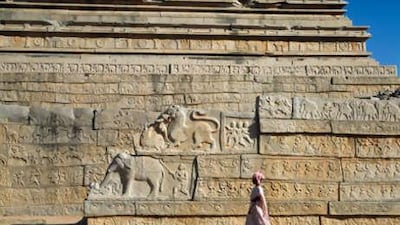

This is the ruined city of Vijayanagara: the city whose greatest ruler, Krishna Deva Raya, conquered all south India from the Bay of Bengal to the tip of Tamil Nadu; a city perhaps three times the size, in its heyday, of Paris, then Europe's largest, its central section alone covering 25 square kilometres; a city which the Portuguese trader Domingo Paes described as "the best provided city in the world", and of which Abdul Razaak, a Persian envoy, said: "The city is such that the pupil of the eye has never seen a place like it, and ear of intelligence has never been informed that existed anything to equal it in the World."

It is also a city that, after its final defeat and sacking by the Deccan Sultanates in 1565, was set alight, demolished and deserted forever, taking its place alongside Angkor Wat and Machu Picchu among the world's great dead cities. Or so I believe, until I meet my guide Virupaksha the next morning for his tour of the village of Anegundi. "They're there, they're living there now, " Virupaksha explains casually, dabbing at a plate of rice and dal in his house.

"There's a Krishna Deva Raya in Hospet, who's the head of the family. As for Anegundi, there's around 60 royal family members living here. The rest of Hampi may be dead, but here it is still alive." Viru, as energetic as he is small and wiry, has gained a modicum of local fame - and a mention in the Lonely Planet guide - for giving tours that start where others finish, ignoring the main Vijayanagara sites, and instead providing a mix of wildlife, prehistoric paintings, living Hinduism and awesome views.

He's based in Anegundi, the fortified village across the river in the far north-eastern corner of the Vijayanagara site that was the the home of the city's founding brothers Hakka and Bukka, and is where, if they are to be believed, Krishna Deva Raya's descendents returned some time in the 17th century. But Viru is wary of introducing Rama Raya, the most senior descendent of Krishna Deva Raya in the village. "If we see him, you must say that you are very short of time," he warns, looking worried. "Otherwise it can take two hours. If you ask one question, he answers 10."

The Royal Palace sits in the centre of Anegundi, its roofs long collapsed, and its walls crumbling. "It's not exactly going to have the tourists flocking," says my friend Oliver. Just one corner courtyard, entered through a collapsed arch, remains inhabited. And there, his straggly hair and beard as blazing white as his light kurta pajama, Rama Raya sits waiting. "This family is the Anegundi royal family," he explains once we sit down. "Long before the establishment of Vijayanagara we were here, and we are here now. Our family is living heritage."

Rama then starts to tell the story of his forefathers after Tirumala Raya, the last ruler, fled the onset of the Deccan sultans, his vast riches piled onto the backs of 550 elephants. They established new a capital in Penukonda, then Chandragiri, and finally in Vellore, from where, after the empire's final defeat, the family drifted back to Anegundi and where, becoming the local gentry, they remained up until Indian independence.

No one disputes this. Back in 1824, the British even awarded the family a 500 rupee-a-year pension to compensate them for Britain's possession of Hampi and the surrounding lands. Rama's brother Achutya only forfeited this as recently as 1984. "I say now that I'm a citizen of independent India, but people still sometimes address us as Raja," Rama says. "Many people come to me also, families and individuals, they come to me to answer their quarrels."

I ask about the collapsed arch. "It happened very recently, baba," he says sadly. "In October, there was a monsoon flood and it collapsed. In 1799, this was a whole complex, it was almost half of the village. But it is ruins and rubble now." It's a fascinating story, but by the time we get ready to leave I'm starting to understand Virupaksha's warning. It's been one and a half hours on the porch, and Rama's story-telling has become a kind of hypnotic chant.

Even when we're walking away, he continues to call after us: "And who fought a war with the Ahmednagar Sultan? That was Krishna Deva Raya. And who fought a war with the Kangani empire? That also was Krishna Deva ..." There are many more ancient remains to see in Anegundi. On a hilltop outside Anegundi, Viru shows us the family tombs. Achyuta Deva Raya, the previous head of the family was buried here in 2008.

The family still owns the old flag and silver seals of the Vijayanagara empire, old swords, and manuscripts going back hundreds of years. It has given its silver throne and its diamond and ruby encrusted crown, which they believe comes from Vijayanagara times, to the head swami of Hampi's Virupaksha Temple. To hear about such ornaments, I need to talk to Krishna Deva Raya, the 38-year-old son of Rama's elder brother Achutya, who in 2008 became the new head of the family, after a six-year stint working for a building firm in Washington DC.

I go to meet Krishna in a hotel in nearby Hospet, where he's attending a meeting of academics celebrating the 500th anniversary of the coronation of his famous namesake. An unassuming, softly-spoken man dressed in a patterned kurta, jeans and flip flops, Krishna says he wasn't brought up with any airs and graces. "I've had a normal upbringing. I was never told, 'you are royal'. But since I belong to this family, I feel I have a duty to protect the site, to educate the people here."

As part of this, he wants to channel some of the proceeds from his family's iron ore mining business into renovating the family house in Anegundi, turning it into a museum where some of the family artifacts can be displayed. "Right now, it looks in a pretty bad shape," he says. "But we have still got the original wooden columns, I have an architect working on it. "I want to restore it. I don't want to renovate it, I want to use lime and mortar, even if it's more expensive."

He thinks Hampi has been badly maintained. "I personally feel that the government could have done a better job, " he says. "You are not supposed to build anything in Hampi, but those are just rules. Because of corruption, a lot of structures are built. At the very least we need to keep it clean. There's garbage everywhere." For now, though, he can't even afford to start work on the crumbling Royal Palace where Rama has his quarters, he says, let alone put money into the rest of Hampi. "I would love to do something for the restoration and preservation of Hampi, but I want to start with my own village."

His son, he says, is more interested in European royalty and the Roman Empire. Krishna, too, is perhaps under-playing the present-day resonance of his royal past. In January, to mark the coronation, he was crowned with a golden turban in front of a crowd of thousands in the Virupaksha Temple, which was lit with strobes and coloured lights. In October, Hampi is also one of the best places to celebrate Diwali, with fireworks, ceremonies and an elephant parade; November sees the giant Hampi Festival, a huge pageant of music, dance and puppet shows.

In March, like his father before him, Krishna takes centre place at the temple's "car festival", which draws in a crowd of tens of thousands of devotees. There could be few more vivid demonstrations of how the traditions of Vijayanagara remain alive. "There's an ancient crown which dates back to the Vijayanagara times. It's made out of gold and it has diamonds and rubies in it. I then put the crown on the swami's head.

"As far as I know, my grandfather used to do it, then my father," he says. "I remember going as a kid to Hampi, just to enjoy myself. Now my son comes. He loves to sit on the elephants." travel@thenational.ae