Fourteen-year-old Khorshid Zamani was a role model for many Afghan girls.

As an instructor at Skateistan, a non-profit organisation that uses skateboarding as a way of promoting social inclusion and youth empowerment in Afghanistan, she inspired and encouraged 160 female skateboarders during her weekly coaching sessions.

On September 8, Zamani was among six people killed by a teenage suicide bomber outside the headquarters of the Nato-led International Security Assistance Force in Kabul. The bomb also claimed Parwana, her eight-year-old sister, who had signed up for skateboarding lessons only a week earlier, their cousin Assad, and two other teenage skateboarders.

Family and friends will remember them today at the International Peace Day festival at the Skateistan facility.

In spite of this terrible tragedy, fellow skaters at Skateistan, including Wahila Mahmoodi, 12, and Fazila Shirindel, 14, are determined to keep their legacy alive.

The pair from Jalalabad in eastern Afghanistan, who are also instructors at Skateistan, scratch out a meagre living by working on the streets of Kabul. According to the United Nations, an estimated 60,000 children wash cars, sell chewing gum or beg in the capital's streets, where nearly half the population is under 14 years old.

Mahmoodi and Shirindel, as well as many other young faces from the streets of Kabul, are the focus of Skateistan: The Tale of Skateboarding in Afghanistan, a new book which tells the story of how the sport is changing young people's lives.

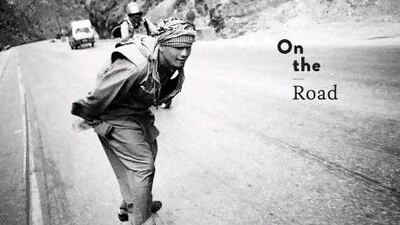

"Skateboarding is something that gave me identity as a youth," said Oliver Percovich, founder of Skateistan, at the book's London launch. He added that he views the sport as a "bridge between all people".

When he first visited Afghanistan in 2007, Percovich found that his skateboard provided him with "an entry point to engage with children" and he resolved to put the sport at the centre of an empowerment project for disadvantaged young people.

Since the opening of the first skate park in Kabul in October 2009, 1,060 children have joined Skateistan, 40 per cent of them girls, and approximately 400 students participate each week. The programme also offers coeducational workshops on art, theatre, music and filmmaking, and its Back to School initiative focuses on educating children aged between six and 15 years old. Its curriculum includes mathematics and Quranic studies.

The book tells the stories of many Afghan girls and boys for whom getting on a skateboard has proved to be a turning point in their lives. While Skateistan: To Live and Skate in Kabul, a short film released in 2010, scratches the surface of the project, the book delves deep into the lives of the Afghans who have helped make the venture a reality.

Wais Ahmadi, 19, for instance, washed cars in Kabul's streets before taking up the sport as a way of battling substance abuse and eventually became the first Afghan instructor at Skateistan. He no longer works for the project, but has been credited with helping to recruit many other young people who had previously found themselves in equally desperate circumstances.

Rhianon Bader, the book's managing editor, says skateboarding plays a key role in empowering young women: "They're more comfortable speaking in public and being around other people. Girls feel they can contribute something valuable and have an important role in their society."

In a poverty-stricken country embroiled in a seemingly perpetual civil conflict, Skateistan serves as a welcome refuge from the harsh realities of everyday life.

Pro skater Maysam Faraj, a Syrian who now lives in Dubai, visited Afghanistan in 2009. Along with other pros such as Kenny Reed and Cairo Foster, both of whom are from the US and have visited Skateistan, Faraj writes about skateboarding with Kabul's street children.The programme, he says, offers "an escape, a good time, an education, a safe haven".

The project's achievements were formally recognised at July's annual Beyond Sport Award in London, where the organisation won the Innovation Through Sport Award. Beyond Sport is a global organisation that uses sport as an instrument for bringing about social change.

The skateboarding initiative has been replicated in Pakistan and Cambodia, and a skate park twice the size of the 1,800 square metre facility in Kabul will open by the end of this year in Mazar-e-Sharif, the capital of Balkh province, giving young people outside the capital the opportunity to get involved.

Nancy Dupree, the 85-year-old director of the Afghanistan Centre at Kabul University, has spent almost 50 years in Afghanistan. She described Percovich's programme as "very imaginative" and believes young Afghans have become much more politically aware and keen to take responsibility for their country's progress. "They've found their voices and more and more are going to speak out," she said.

Projects such as Skateistan "create bonds and build social capital", according to Percovich, who dismissed claims that the programme intrudes on traditional Afghan culture and attempts to inculcate children with western values. He insisted that what has emerged is an "Afghan style of skating" that is independent from western skateboarding culture.

Amid a political crisis and ongoing violence, Bader, who spent more than two years working on the book, said she wanted to "show the positive side of Afghanistan, the hope of the youth. It's just a reminder that there are people, especially children, in this country. And children just want to have fun."

Percovich, the non-profit organisation's ambitious founder, hopes that the book will become "a document that covers a point in time in Afghanistan's history. It's an attempt to get the voices of the Afghan youth heard all around the world." He fears that if the needs of disadvantaged young people are ignored, they could fall prey to extremism or become involved in the drug trade.

Despite the recent tragedy, Bader said in an email to The Review that "[Skateistan] will continue to do what it does - helping to provide light in the lives of hundreds of kids we are working with weekly, as well as opportunities for them in education".

Echoing that sentiment, Shirindel says that in the future she either wants to become a doctor or a pro skateboarder, but does not rule out another related occupation either. "My mother always tells me I can become anything I want," she says. "I would also like to become the first Afghan director of Skateistan."

Bibek Bhandari is a freelance journalist based in London.