As Danny Boyle strode up to the stage at the Beverly Hilton Hotel in Hollywood to collect the fourth Golden Globe of the night for Slumdog Millionaire, Sagar Kamaliya had already been up and about for hours.

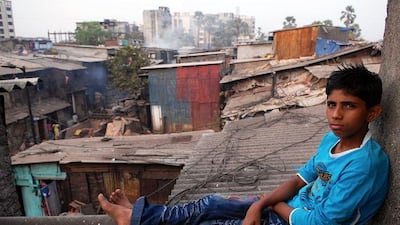

Half a day and 8,710 miles away in Los Angeles's twin city of Mumbai, the sun was already high over the tin and asbestos rooftops of the tightly packed mass of houses and workshops that make up Dharavi, Asia's largest slum and the setting for the Oscar front-runner. While Boyle was thanking the Globes audience for "your mad, pulsating affection for our film", the one million people who live in the mad, pulsating slum of Dharavi could have been forgiven for wondering how poverty had suddenly become so chic.

Outside his home in the potter's colony, Kamaliya would have been putting the finishing touches to another clay pot and thinking about getting ready to head off to college. The pots are lined up outside the two-room house that the 17-year-old student shares with his mother, Lalita, and father, Bhanji, as well as two younger brothers, Sanjay, 15, and Nayan, 13. They all sleep on mats on the floor of the lower storey, which also serves as the kitchen and living room. The room upstairs is used for storing the finished pots.

It may be a far cry from the glitz and glamour of a Hollywood awards ceremony, but Sagar is still making an effort, wearing his best top, a smart, blue, long-sleeved T-shirt and new jeans. He likes clothes: the 10 rupees pocket money he receives from his parents each day is stashed away until he can afford a new item. He has four T-shirts, he explains proudly, two pairs of jeans and one pair of shoes.

The money comes from the sale of the pots: the family might expect to sell 150 a week at 70 rupees for a large pot. For two hours a day, Kamaliya fixes lumps of clay to the bases of the pots that will form the legs once they are fired and makes a hole in the side into which a tap will be fitted. His parents may be content with their lot, but Kamaliya dreams. He doesn't mind the slum, though he thinks it a little dirty and worries that people fight and use bad language.

But he dreams of one day getting out, of making something more of his life. As soon as he has finished with the pots, he heads off to the college where he is studying to become an electrical engineer. "One day I will buy a house outside [Dharavi], a bungalow with a lot of rooms and I'll get a big car, a Toyota, and a TV and a fridge and I'll have air-conditioners." Outside Kamaliya's house is a small pond of bright green, scum-covered water in which float the bloated bodies of two dead rats. Until Boyle and his movie came along, that was all the rest of the world ever heard about Dharavi. The 535-acre former fishing village was a byword for squalor, a place of free-running rats and open drains where 1,800 people crammed into each acre and average family earnings rarely topped 15,000 rupees (Dh1,125) a month. But the 66th Golden Globe awards have changed all that. Slumdog is, by all accounts, an astonishing piece of work, with one third of the dialogue in Hindi and much of it shot in the slum. On Sunday night in LA, it won the awards for Best Picture and Best Director as well as Best Screenplay for the Full Monty writer Simon Beaufoy and Best Original Score for the Indian composer AR Rahman. A week earlier, it had nailed five awards at the US Critics Choice Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director. Based on Vikas Swarup's best-selling novel Q & A, it tells the story of Jamal Malik, a teenage boy from the slums of Mumbai who goes on Kaun Banega Crorepati, India's own version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, in the hope of finding his childhood sweetheart, who watches the show avidly. When he beats the odds to get through the final questions, he is arrested. How, the police ask him, could a boy from Dharavi know the answers? Yet, as the world starts to look at the slum in a different light, such questions already seem anachronistic. Dharavi may be up to its ankles in dirt, but if the inhabitants notice, they don't let it stop them getting on with their lives. The drains may not give off the sweetest aroma, but Dharavi does not have the smell of defeat. Most people have jobs and the children go to school. A beggar is as rare as a Rolls-Royce on the streets of Dharavi. Devendra Tank, 21, epitomises the future of Dharavi. Smartly dressed in a white Barclays Bank T-shirt, he used to show tourists round the slum. Now, he works for the international finance firm JP Morgan. In his spare time, he is studying for a master's degree in commerce; once that is under his belt, he plans to move on to do an MBA. He was one of only eight boys from his college to be selected by the firm, out of 200 who applied. He makes about 15,000 rupees a month, a small fortune by Dharavi standards, but he still helps out in his parents' pottery business at the weekends. Like Kamaliya, home is still a one-room house shared with his parents and three sisters. When the girls want to get changed, he is kicked out onto the street. But why move, he asks? There is nothing much wrong with Dharavi. It is a view shared by 14-year-old Mohamad Ashraf. Dressed in a smart brown shirt and blue jeans, he is sitting on the rooftop of a plastic recycling warehouse, fiddling with his cell phone and texting friends. His father runs a tobacco business, which is clearly successful. The family owns a second home outside Mumbai, where they sometimes stay, though Ashraf says he prefers Dharavi because that is where most of his friends live. Like the others, he and his brother, sister and parents share one room in the Dharavi house, but he says, so what. At least he gets his own bed, and there are plenty of boys his age in India who cannot say that. When he is not at the Urdu school he attends during the day, he likes to hang out with his best friend Fayaz. "Sometimes we'll just wander around, sometimes we'll go to play games in the cyber cafe," he says. The corrugated walls of many of the buildings have one big advantage for a young boy: "I can play cricket anywhere here because there are no windows to break," he says. His father gives him money to buy kites and go to the movies every Saturday. Ashraf doesn't really want to live anywhere else. When he leaves school, he thinks it might be fun to join the traffic police. "There was a short course on the police in school and I got a certificate," he says. "I want to stand in the middle of the street and direct the traffic." His friends look at him oddly, but he seems to be serious. There is nothing of the freak show about the boys, or the tens of thousands like them living in Dharavi and working hard to better themselves. Yet, it is possible to take a sightseeing tour of Dharavi, and many tourists do. Those who live there view the interlopers with a degree of acceptance, though some bridle at being treated as exhibits in a poverty zoo. Reality Tours and Travel, which runs the tours, claims it is breaking down the negative image of India's slums and the people who live there. "The beauty of Dharavi lies not on the main roads but in the small hidden alleys where thousands work and live in a number of small enterprises, where goats roam freely and where children play with carefree abandon," its website promises. Krishna Pujari, who has been running the tours for three years, says those who take them are won over by what they see. "People have a negative image that it is dangerous, that there is crime and the children are not going to school, but we are showing them a positive side of the slum." And though Pujari might not put it quite this way, Slumdog has triggered a boom in poverty tourism. "After the movie, there are a lot of people coming on the tours," he says. "More and more people are coming." Slumdog does not even open in India until Jan 23, but it is already on the front pages of India's newspapers as the country claims the movie as its own. In its lead editorial the day after the Globes, The Times of India trumpeted the success of Rahman as it welcomed the way that an uplifting movie had managed to balance fantasy with a "stark look at the life of the urban poor in India". Its news pages, in which it describes the film as "a frenzied romp through the bowels of the Mumbai slum", asks, "Has the movie become Indian Underbelly Shining?", a play on the popular political slogan India Shining used by the nationalist BJP party to great effect in the 2004 general elections to trumpet India's successes. "Be it Aravind Adiga's Man Booker-winning The White Tiger or Slumdog, the unpalatable realities of asli [real] India are up there under the strobe lights for the world to gaze on. From snot-nosed children to the oppressive caste system, it's fodder that is being reloaded anew... this is probably the first time that the worst of India is being showcased to worldwide commercial acclaim." The Indian Express felt India could take the film's triumph personally, even before it hit the cinemas. "With significant Indian participation in the making of it, Slumdog Millionaire is our biggest crossover success story in film so far... much like its own rags to fabulous riches narrative arc." The paper's media critic, Shailaja Bajpai, thinks the movie could mark a watershed in attitudes not just to Dharavi but to India as a whole. "India's underbelly is being exposed but it is also winning applause abroad," she says. "It is not something we should be running away from and the interesting thing is that is very aspirational. Here's a young boy who is trying to improve himself and I think that's a major departure. It may be using the seamier side of India, which is stereotypical, but it is showing a positive side and I think that is going to be a good thing." But if India has taken the movie to its heart, will Indians watch it? Bajpai is not so sure. She wonders whether the grim realities of Indian life are what Indian cinema audiences really want. "It is not that we are unaware of it, we live with it every day. We know about Dharavi and Mumbai. If you live with it every day, do you really want to see it up on the screen?" It is a question that some in Dharavi are also asking themselves. "Because I stay in this life, I would rather see Terminator, Matrix or the Omen," the 21-year old Dharavi resident Vikas Miashra told the Hindustan Times the morning after the Globes. "I prefer American films because I am more interested in seeing their life." As Hollywood gears up for the Oscars, though, the rest of the world only has eyes for the lives of those who call Dharavi home.