Although practised across the world, consanguineous marriages - the union between close family members – have been condemned by scientists. The topic has always made for a good debate.

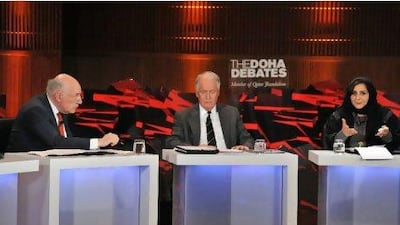

Last week, The Doha Debates held its regular one-hour session under the banner "This House believes marriage between close family members should be discouraged", making it possibly the most sensitive social subject the forum has tackled to date. Discussions hit close to home in Qatar, where more than 50 per cent of marriages are between people, as the Debates' founder and presenter Tim Sebastian put it, "joined by the ties of blood".

Some 316 ticket-holders attended the talk, which will be televised on BBC World News on Saturday, and took the format of the Oxford Union, Britain's 189-year-old prestigious debating society. The predominantly Arab audience, most under the age of 35, included three visiting student groups from Sultan Qaboos University in Oman, the American University in Paris and the University of Sharjah in the UAE.

The temporary studio was erected inside a lecture theatre at Georgetown University's School of Foreign Service at Qatar Foundation.

"Much has been written about the increased risk of genetic disorders being passed on through marriages of this kind," said Sebastian, as the cameras began rolling. "Should these marriages continue to be sanctioned or is this no place for the heavy hand of the state or medical experts to weigh in and interfere?"

The British Pakistani journalist and cultural commentator Sarfraz Manzoor argued for the discouragement of cousin marriages, alongside Ohad Birk, an Israeli geneticist and the head of the Kahn Genetics Research Centre at Ben Gurion University. The Saudi Arabian writer and columnist Samar Fatany spoke against the motion and was supported by Alan Bittles, adjunct professor, the research leader at Murdoch University's Centre for Comparative Genomics in Australia and, according to The Guardian newspaper in 2008, "the world's leading authority on cousin marriages".

Three major themes kept re-emerging: the affect on society, the level of risk in terms of increasing genetic disorder and the religious guidelines.

"In Qatar, you've got all this money but you've also got the greatest prevalence of diabetes, obesity and genetic disorders in the world and cousin marriages are the reason," said Manzoor, who admitted his family once attempted to arrange his wedding to a cousin. "I think society is healthier when more communities mix and integrate; the more families marry within each other, the less chance of creating an integrated society."

But for Fatany, whose parents are cousins, "cultural and religious reasons" make it difficult to warn people against marrying within. "Families feel comfortable if a daughter marries within the family," she said, "rather than marrying a stranger with no background."

Islam forbids men and women to mix freely beyond the family's borders, she added, and that, combined with the Quranic justification - the Holy book doesn't rule the practice out - makes it permissible.

"You usually have the cousins falling in love and parents wouldn't stand in the way of love," she said. "Some families feel offended if a graduate who just came home, when there are so many pretty girls in the family, decides to marry outside the family. It's frowned upon."

Sebastian, speaking on religion, responded that there is a body of opinion in Islam that believes the Prophet Mohammed himself disliked consanguinity, as he quoted a Hadith (a saying of the Prophet). "Marry those who are unrelated to you, so that your children do not become weak."

But that is a saying that is itself debated, and one which is contradicted because of intermarrying within the Prophet Mohammed's own family, a point the opposing team happily leaned upon.

Scientific facts were used to pin up arguments, such as those related by Birk. He has worked with an Arab Bedouin community of around 200,000 on a daily basis over the past decade. Sixty per cent of those in the group marry first or second cousins. They are, he said, four times more likely to have children with defects.

"Statistics show that worldwide, the chances of having a child with a severe birth defect is around three per cent. In first-cousin marriages, it goes up to six or seven per cent. In fact, if marriages in the family have been going on for generations, it goes up to 10 per cent or more," he said, adding that marrying a second or third cousin dramatically reduces the risk posed to offspring.

His job is often a depressing experience.

"Two days ago, a couple came into my office with their two bright, beautiful girls, both born with no eyes. They had no eyeballs. This couple is devastated."

A week before that, he visited a high-school teacher who had married a family member and had three children, now ages 23, 20 and 18 - all severely mentally and physically challenged.

Even Bittles, who argued against the motion and said some statistics offered by his opponents were "spurious", admitted that there is an "increased risk" of deformity among first-cousin offspring.

In 2008, he was quoted by Sebastian as saying that the chances of a couple's children from the general population having a deformity stands at two per cent. If cousins marry and have children, the chances double to four per cent.

"From two per cent to four per cent, that's double the risk," said Sebastian, as he rigorously probed the speaker. "In general, people should be encouraged not to take increased risk. We're asking for a red traffic light at the junction."

To which Bittles quickly retorted: "You're the red traffic light guy. I'm the amber guy. I might give a warning signal. But you have got to put that extra two to four per cent in context."

There are tools in place, especially in the Gulf, to reduce the level of risk to children. Premarital genetic testing screenings are mandatory in many states, including Qatar and the UAE.

But, "genetic testing has its limitations in first-cousin marriages," said Birk. "There are also genetic diseases that are unique to each family and there is no way that a screening programme would find them."

As consanguineous relationships show little sign of disappearing, there was a consensus among the speakers for undergoing such testing. Unfortunately, however, a trend has emerged showing that even when parents are informed of a significant potential risk, they tend to ignore doctors' advice.

A specialist geneticist at Shafallah, from a special needs centre in Qatar, told The Doha Debates that there's "no counselling to help people make decisions. Even if the results show one or both parents to be a carrier, the attitude is usually, 'Well carry on regardless, everything will be OK, Inshallah'."

Even Bittles, who became personal on a couple of occasions during the discussion (he branded Manzoor a "joker" and accused Sebastian of changing the subject too quickly because they couldn't handle his statistics) agreed. "At least half of the people who have the test and find out that they are both carriers proceed with marriage anyway," he said.

And so, to the final minute of the debate - the moment the audience gets to decide. They voted electronically for or against the motion, a practicality that took just 15 seconds.

Eighty-one per cent said marriage between close family members should be discouraged. Just 19 per cent disagreed.

• The debate will be broadcast on BBC World News on Saturday

Follow

Arts & Life on Twitter

to keep up with all the latest news and events