Meissen, the German porcelain manufacturer famous for ornate tableware and baroque figurines that have graced Europe's royal palaces for 300 years, has survived the economic downturn with a radical overhaul that has propelled it into the 21st century.

In just 12 months, it has branched out into contemporary interior design products such as tailor-made wall and floor tiles for the palaces of the modern age - top-of-the-range hotels and luxury stores. It has also launched table services for sushi, pasta and espresso to suit younger tastes, and introduced a new jewellery collection, along with watches and pens to take on the likes of Cartier, Bulgari and Hermes.

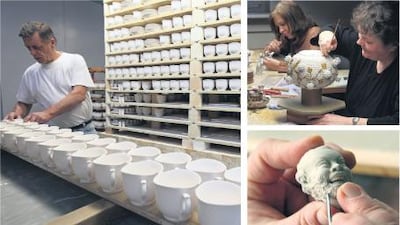

The changes amount to nothing less than a revolution at this ancient factory in the sedate, picturesque town of Meissen, located in the Saxony region of eastern Germany. Some 800 employees, many of them artists and highly trained artisans, have spent decades working off designs that date back as far as the 18th century. Its trademark, two crossed swords, is the world's oldest brand in continuous use.

The aim is to establish Meissen as a global luxury brand for the three newly organised segments - fine living, fine dining and fine jewellery - and to protect the heritage of the company that invented European hard porcelain, says Christian Kurtzke, the chief executive. A former Boston Consulting Group executive, he was brought in as manager in 2008 to restructure the loss-making firm. "This factory has enormous untapped potential," Mr Kurtzke, 40, said last month ahead of the opening of an exhibition to mark the company's 300th anniversary.

"One of the first things that struck me when I arrived here was how Meissen is like a monastery, it has its own rhythm of time," he said. "We're going to keep that despite all the necessary process optimisation. But marketing, distribution and communication have been neglected. We've got to speed up product cycles, use modern technology and embrace the internet." Mr Kurtzke, originally from Berlin, says the new strategy had already paid off last year, when revenue from Meissen's new interior design range helped offset sharp declines in key markets such as Russia, where sales dropped by two thirds.

The crisis claimed the rival Irish china maker Waterford Wedgwood and its German unit Rosenthal, both of which went bankrupt last year. "Sales in 2009 will almost match the 2008 level of ?35 million [Dh178.1m], not because we were spared the financial crisis, but because we were able to compensate all the declines with our product innovations," says Mr Kurtzke, who oozes reforming zeal and looks out of place in the old corridors of the red-brick factory with his fashionably tight grey-striped suit and purple tie.

He says the fine living segment alone, with its new wall panelling and tiling ranges, has attracted interest from architects and has the potential to double the company's overall sales in the medium to long term. Meissen's new products contributed 10 to 15 per cent of sales last year. Mr Kurtzke declines to give a figure for last year's earnings and says he cannot predict when Meissen will return to profit after it lost ?6m in 2008.

"I had to change everything so that it can stay the way it is," Mr Kurtzke says. That seems a little exaggerated. Meissen could probably afford to go on making losses indefinitely because it is wholly-owned by the state of Saxony and considered too valuable to be allowed to fail. It remains one of Germany's strongest brand names and many of the 200,000 products in its repertoire, all of which are handcrafted, are cherished collector's items, rivalling gold as a long-term investment.

"As an investment, Meissen porcelain has performed consistently for many years. It is by far and away the most revered and collectable porcelain," says Philip Howell, the head of European Ceramics at the London auctioneers Sotheby's. "Over the last two or three years there have been some extraordinary prices for Meissen porcelain." A harlequin figurine from about 1740 fetched £400,000 (Dh2.3m) at Christie's two years ago.

Meissen owes its status to a stroke of luck. The Elector of Saxony, Augustus the Strong, reputedly so physically powerful that he could bend horseshoes, was having a cash-flow problem and seized a young alchemist, Johann Friedrich Bottger, who had unwisely claimed he could make gold. In 1705, the king locked Bottger up in Meissen's castle, the Albrechtsburg, to encourage him to speed up his research. Bottger failed to come up with gold, but his experiments led to the secret of making white porcelain in 1708. That was almost as good as gold because Europe had been trying for centuries to copy the hugely expensive imports of East Asian porcelain that had begun arriving in the 16th century.

On January 23, 1710, the Saxon court announced the invention of Europe's first hard-paste porcelain and the foundation of the company. The factory gets its raw material, the clay mineral kaolinite, from its own mine, and has created its own stock of 10,000 dyes for painting. Mr Kurtzke says he has no intention of changing Meissen's production methods because they are the key to the brand's success.

"The financial crisis has split the fashion industry into two segments: the premium brands which largely produce industrially; and the factories whose growth is inherently limited because they are true handicraft businesses," Mr Kurtzke says. "Meissen will remain faithful to its traditions," he says. "It never diluted its quality, never outsourced, never industrialised and always resisted the temptation to become too democratic, unlike other brands."

The craftsmanship will guarantee its long-term future, he says. "I'm sure that the idea of value, and the desire to bequeath fine objects from generation to generation, will see a big renaissance. So many things these days are fashionable and consumer-oriented, but where are the true values?" @Email:dcrossland@thenational.ae