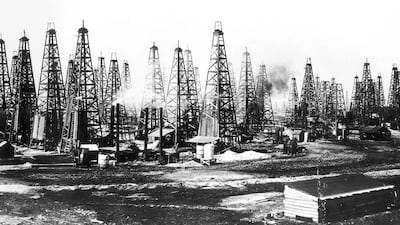

Extreme volatility and strong cyclicality have been the defining characteristics of oil prices and the industry since the first modern oil well was drilled in Pennsylvania in 1859.

This volatility is apparent at all time scales from the very short term (tick-by-tick and daily movements in futures prices) to the longer term (month-to-month and year-to-year). But price moves are not random and display clear evidence of cyclical behaviour, again at all time horizons from the very short term to decades.

Volatility and cyclicality are not incidental features of oil markets that can be wished or managed away. Volatility and cyclicality are fundamental characteristics of oil markets.

Prices, production and consumption do not return promptly and smoothly to equilibrium following a disturbance to the market.

"The problem of oil is that there is always too much or too little", Myron Watkins, professor of economics at New York University, wrote 80 years ago (Oil: Stabilisation or Conservation? Watkins, 1937).

"The basic feature of the petroleum industry ... that matters most is that it is not self-adjusting", according to the economist Paul Frankel (Essentials of Petroleum, Frankel, 1946).

Because of the lack of adjustment mechanisms the industry has “an inherent tendency to extreme crises” and “hectic prosperity is followed all too swiftly by complete collapse”, Frankel argued.

The industry has defied repeated attempts to tame the cycle and provide greater stability.

Frankel’s description has remained accurate for six decades and his book remains the best primer on the oil business.

Frankel blamed boom and bust on the sluggish response of both production and consumption to even a large change in oil prices. The lack of ready substitutes for oil as a transport fuel and in petrochemicals ensures consumption responds slowly and in a limited way to a change in prices.

Capital intensity and the high ratio of fixed to variable costs in all parts of the supply chain from exploration and production to refining and marketing ensure supply is also price-inelastic in the short term.

Low price-elasticity of both supply and demand are what Frankel meant by lack of “self-adjustment” in the industry. But other factors besides low-price elasticity contribute to the extreme instability and cyclicality of oil prices.

Given the capital-intensive nature of the oil business, investments in new production capacity and changes in production take a long time.

Bringing a complex offshore oilfield on-stream can take 10 years from discovery to initial production. Training experienced seismologists, drilling supervisors and petroleum engineers can take even longer. The oil industry’s mass layoffs during the price slump of the 1990s were still hampering its ability to increase production a decade later, contributing to the price boom of the 2000s.

By their nature, investment decisions must be based on expectations about where oil prices will be in three to 10 years when projects come on-stream and then over the succeeding 10 to 20 years of field production.

But there is evidence that expectations, which are meant to be forward-looking, are strongly influenced by the recent past, introducing a backward-looking element. Oil companies are generally too bullish about future prices following a boom and too bearish about future prices following a slump.

Backward-looking expectations coupled with long delays in bringing new capacity on-stream contribute to the cycle of under and oversupply.

The same problem is also apparent on the consumption side, where households and businesses entrench often backward-looking expectations about future prices in purchases of long-lived capital equipment.

Negative feedback mechanisms dampen the effect of an initial disturbance and therefore promote a rapid return to equilibrium.

Fuel-switching, efficiency and energy conservation policies are all negative feedback mechanisms on the demand side of the market which promote an eventual return to balance.

Capital budgets, cash flow and the availability of debt and equity finance all act as negative feedback mechanisms on the supply side.

But there are also positive feedback mechanisms which amplify and prolong the effect of an initial disturbance and are therefore destabilising and delay return to balance.

Producers’ revenue needs and changes in fiscal terms and the cost of labour, raw materials and service contracts are all examples of positive feedback loops. The GDP impact of an oil-price slump on the internal oil consumption of oil-producing countries is also a source of positive destabilising feedback.

Each market is subject to its own feedback mechanisms, operating at different speeds and different time scales. Rebalancing the oil industry actually means rebalancing all of these markets simultaneously. As a result, the oil industry can be thought of as a system that exhibits very complex and chaotic behaviour where small changes in one part of the system can trigger very large changes in the rest of the system.

Recent experience has shown how a small change in technology (horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing) in one small part of the oil industry (US shale) helped to trigger a slump in prices.

The worst of the slump appears to be over, but past experience implies that instability will also characterise the recovery.

In the past, slumps such as 1997-98 and 2008-09 have usually been followed by a very large rebound in prices. Oil prices more than doubled between December 1998 and December 1999 and again between January 2009 and January 2010.

In the current episode, US crude prices have already risen by almost two-thirds, from an average of less than $32 per barrel in January 2016 to an average of almost $53 so far in 2017.

Some analysts predict the rise of the US shale industry will lead to a new oil market structure, with more flexibility in production, greater price stability and prices capped around $60 or $70 far into the future.

But past experience suggests the process of adjustment has rarely been so smooth and orderly; it would be unusual if this time was different.

* Reuters

business@thenational.ae

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter