A friend once told me over lunch his theory that the people of the Levant, no doubt due to their Phoenician trading roots, are essentially a transactional people who have been weaned on the culture of paying for a good or service: something for something, in other words.

And maybe this is why we Lebanese, if we are being honest, have a difficult relationship with advertising. What the industry calls “above the line” (ATL) activities – TV, radio and print media ads – we get, but only because it’s been around forever and has woven itself into our business culture. But the fact remains that we can’t help feeling that we might essentially be throwing money at an idea that may or may not improve sales. There are no guarantees. It’s not like buying a new galley or selling olive oil, purple dye or glass.

It’s even harder for us to hold our nerve when it comes to “below-the-line activity” (BTL), money spent on promotions or PR campaigns where the returns are even harder to quantify and where we are told it can take years to see results.

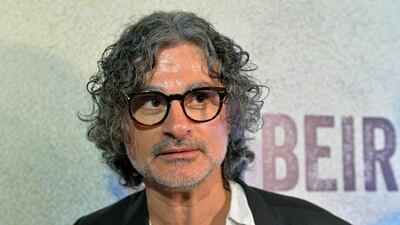

I was thinking about all this when I read that Ziad Doueiri, the Lebanese film director who gave us the delightful West Beirut and whose latest film The Insult inspired a prolonged standing ovation at this year's Venice Film Festival, had been arrested on charges of collaborating with Israelis in the production of his 2012 film The Attack, a film about a Palestinian doctor who discovers his wife is a suicide bomber.

Lebanon's film industry is boutique, to put it kindly. The talent is there and every couple of years it throws up a film of promise that makes a few international waves. But when one, like The Insult wins a major prize – Kamel El Basha won the Volpi Cup for Best Actor – at one of the most prestigious festivals, then the moment needs to be leveraged to the max.

Films can put a country on the front burner even if The Insult isn't The Lord of the Rings and Lebanon, sadly, isn't New Zealand. In fact the film focuses on the very sensitive sectarian tensions that simmer near the surface of Lebanon's supposedly harmonious society, in this case an argument that develops and then escalates between a Christian and a Palestinian. It's also set in parts of Beirut, which by and large have lost most of their Ottoman and colonial charm.

_______________

Read more:

Fresh ‘fight against corruption’ fails to impress Lebanese

Lebanon parking is in a world of its own

_______________

So it’s hardly an ATL ad for Lebanon. It doesn’t showcase what natural beauty we have left; it doesn’t offer a platform for Arabic music or celebrate our food and wine, nor does it explain the delightful quirkiness of our society. In fact all it does is show how wounds from the civil war have not truly healed.

But the BTL opportunities do offer a bit of traction. Surely if a film is brilliant then somehow that country also has a degree of cool, especially as Beirut, despite everything has stubbornly clung to its pre-civil war glamour. In 2012, Iran briefly came in from global isolation when film fans decided that The Separation, the Oscar winning movie by Asghar Farhadi, was worth a trip to their local indie cinema.

Then there is the impact a successful film can have on a nation's budding filmmakers. Apart from Doueiri, the director Nadine Labaki, who directed the relatively successful 2007 film Caramel, a drama set in and around a Beirut hairdresser, as well as Where Do We Go Now? in 20011 and Philippe Aractingi - the director of 2005's Bosta - are the only other filmmakers to really poke their heads above the international parapet. Before that, one had to go back to the late Maroun Baghdadi whose Beyrouth Hors La Vie won the Special Jury Prize at Cannes in 1991.

The point is that the more Lebanese movies that make it, the more chance of a there being a genuine Lebanese film industry. I have just come back from Lebanon where I have been making a documentary with filmmakers with an abundance of talent and passion. The willingness to work is there. It’s just a shame the state won’t throw more money at the sector. A burgeoning film industry would add a layer to our identity: small country; fabulous food; lovely people; and stunning films. Why not? But most importantly, it creates momentum, a national feel-good factor, which, let’s face it, never really hurt anyone.

So why arrest a national hero? Yes, Doueiri did technically break the law – Lebanese are not allowed contact or collaborate with Israelis – even if his argument at the time was that that he filmed in Israel for authenticity. But the reality is that Lebanon’s law regarding its citizens and the Zionist entity is quite leaky and has been broken on numerous occasions, often by higher profile people.

Bottom line: the message his arrest sent to the world was that Lebanon was a country not in a hurry to congratulate one of its sons for an international artistic triumph but summon him to one of its controversial military courts. It was short-sighted but thankfully someone, somewhere was able to get the charges dropped.

Still, as my friend might say, there is no such thing as bad publicity.