As Libya emerges from a six-month civil war, it faces a long to-do list, from restoring the flow of drinking water to establishing a permanent government.

Editor's Pick: The big business stories making headlines today

Al Jazeera leader quits after 8 years Wadah Khanfar is to quit his position as director general of Al Jazeera, departing on a high note following the network's acclaimed coverage of the Arab Spring. read article

Boost and warning for airlines from Iata Middle East airlines are expected to make $800 million this year, up from a forecast of $100 million three months ago. Read article

Gulf states press ahead with plans for rail networks Governments in the region are pushing ahead with rail link projects to transport passengers and boost trade. Read article

But the most critical part of the nation's rebuilding effort for now is reviving oil production, said the head of Opec, who is also a former Libyan oil minister.

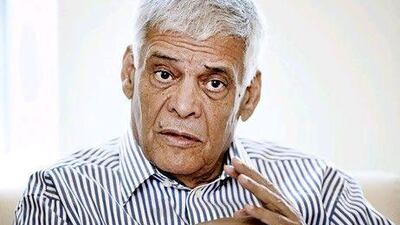

"Concentrate on your first priority," Abdalla El Badri, the Opec secretary general, said yesterday in Dubai, stipulating that he was offering an opinion rather than advice.

"You need that money to calm the country down, to pay your salaries, to buy your food, to buy your medicine."

Before the uprising began in February, Libya pumped about 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd) of oil and sent natural gas to Europe, which together accounted for an estimated 80 to 92 per cent of government revenue.

The crude, which accounts for 1.5 per cent of the world's supplies, was all but wiped from global markets by shutdowns and sanctions, and now Libya's transitional leaders are racing to restore it.

The timetable for the restoration of Libya's light, sweet crude is critical to oil prices because it is highly valued by European refiners.

Yesterday, National Oil Company (NOC), the state producer headquartered in Tripoli, said it was pumping 100,000 bpd from the Sarir and Messla fields.

Estimates for restoring Libya's pre-conflict pumping levels range from six months to three years.

Mr El Badri has said 15 months could suffice, given the right security for workers and oil installations.

Mr El Badri served as chairman of NOC during three stints from 1983 to 2006 and negotiated the country's production policy at Opec.

The fall of the regime of Muammar Qaddafi has led to questions of Libya's willingness to find new foreign partners, increase its production to as much as 3 million bpd or even relocate the headquarters of NOC from Tripoli in the west to the eastern city of Benghazi, the seat of the opposition.

"I really don't want to give advice to anybody in the Libyan oil industry, but I will give you what I am thinking," said Mr El Badri.

"I am thinking the priority at this time is to restore production, to put the oil industry as it was before this revolution.

"And then you start thinking about how you're going to reorganise your industry.

"Right now, concentrate to restore your production, try to cooperate with your partners as much as you can to put everything in order and then you can have time to reorganise yourself."

The promise of a new government in Libya has sparked speculation that Mr El Badri could return to his home country to run its core industry.

Yesterday, he brushed off the possibility, saying he would serve the rest of his term in Opec and then retire in Libya.

"I love Libya, I love my people, I spent all my life in the oil industry in Libya," he said.

"When my term is over I will go back."