If versatility can keep a person sharp, then photographer Germaine Krull’s blade was never dull.

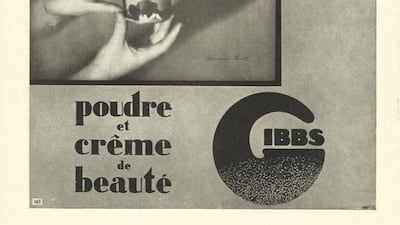

Krull was one of a few women exploring the medium during the era known as the golden age of photojournalism. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Krull refused to limit herself to one genre and explored reportage, industrial landscape, portraits, advertising and experimental photomontage.

As a more anonymous member of the 1920s artistic movement known as “New Vision” (Neues Sehen), Krull possessed a drive for creating images with unusual angles and dynamic framing styles. She and her colleagues imagined a world beyond the static and limited photographic techniques of the past.

Krull believed that a photo book itself was the end product, unlike many of her peers who preferred to let their work be shown in galleries. She published a number of monographs and her photo book Metal (1928) remains her most widely acclaimed publication featuring angular images of the masculine, industrial landscape of Paris, Marseille and cities in Holland.

Much of her work from this era is now featured in a Paris exhibition and displays 130 vintage prints, in addition to documents, magazines and photo books. As a working artist, Krull understood she was in the centre of an evolving medium and took every opportunity to make meaningful work.

• Germaine Krull (1897 to 1985): A Photographer’s Journey runs at the Jeu de Paume in Paris until September 27. For more information visit www.jeudepaume.org.

RJ Mickelson is a photo editor at The National.