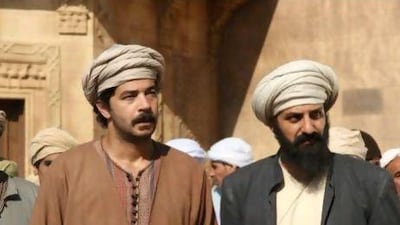

In the hot Cairo sun, the well-known actor Sherif Salama leads an angry group of Egyptians through an Ottoman-style town square.

The town mayor comes out of his home to hear their comments, and asks to be allowed to dress before he follows them to speak with the French military leader, Napoleon Bonaparte.

As the heavy doors close behind him, the mob realises it is a trick: the mayor has no intention of returning. Outraged, they pelt the door with stones. But only until the director yells "cut".

I am on the sets of the Ramadan drama Napoleon Wel Mahrousa, where the stones are painted rubber, the doors are decorated with geometric stencils reminiscent of the ivory inlays of the era, and the surrounding walls are made of styrofoam.

Set in the late 18th century, the serial showcases the lavish sets and ornate costumes that have come to define Egyptian period dramas. Napoleon Wel Mahrousa depicts the effect of the French leader's arrival in Egypt through the lens of an Egyptian family, combining historical facts with the dramatics that characterise Ramadan soap operas.

"I think the series treats the history of the event quite fairly. It's a pretty accurate depiction of the life of Egyptians in the 1700s," says Salama, who plays a revolutionary figure fighting against the French invasion. "We don't want to pinpoint any lesson or idea but just allow people to think for themselves."

At the end of the take, we wait. Ten men, split between three cameras, adjust their positions and plan out new angles to shoot. Sweaty actors dab their foreheads with handkerchiefs as the make-up artist weaves through the crowd, fixing smudged foundation and regluing drooping beards.

Though the series began airing on the first day of Ramadan, its actors and crew are still busy shooting the final episodes. The days are long, Salama says, mostly spent on outdoor sets or in the desert.

"It's been torment. We spent a week shooting chase scenes outdoors in 42-degree heat. For two days I had to run up sand dunes over and over again, all the while acting as though I'd been shot in the leg," says Salama.

Typical of these 30-episode soap operas, Salama is joined by other big names in Egyptian cinema, such as Laila Elwi and Arwa Gouda.

For many of the actors, the opportunity to work with the Emmy-winning Tunisian director Shawqi Al Majri had them signing up for the project.

"He has an eye for detail that refines everything to really reflect the era, and this helps you on your journey as an actor," says Gouda, who plays a widow who refuses to remarry.

"You're learning to speak in an older form of the language, walking differently and dealing differently with everything. Meanwhile, Al Majri is concerned with the whole picture – he concentrates on every dab of paint on the wall, even if it won't be seen on the screen."

Between takes, the head of set decoration adds last-minute touches to the palace wall while Al Majri instructs the actors. After a few minutes, the cameras roll again.

Across the Middle East, mosalsalat – the Arabic word for television soaps – has become as much a part of Ramadan as fasting and prayer. During the first two weeks of Ramadan last year, television viewership rose by 30 per cent across the region, according to IPSOS, a French market researcher with offices in Dubai.

First aired in the 1960s, Ramadan soaps began capturing wider audiences after the rise of pan-Arab satellite stations in the 1990s. Now, Ramadan is associated with the region's best television – and the highest ratings of the year.

"These shows have certainly changed people's experience of the Holy Month," says Christa Salamandra, an associate professor of anthropology at City University in New York, who researches Syrian soap operas.

"People look forward to [Ramadan] as a time to reflect, and rather than mitigating or undermining it, I think TV has enhanced the process of reflection, both personal as well reflection on culture and history."

According to Salamandra, because an increasing number of people in the Arab world now look to television as a source of information, these dramas have begun to address important social questions. Compared to Western soap operas, mosalsalat often are historical epics that raise discussion about taboos in society, such as drug use.

Far from being mere entertainment, some of these serials have even sparked serious political and social tension in the past. According to Salamandra's chapter in Soap Operas and Telenovelas in the Digital Age, both Turkey and the US have successfully lobbied against airing programmes they felt threatened their national interests.

In 2008, two historical dramas were dropped midseason after tribal groups in Saudi Arabia said the shows were inciting tribal tension. Last month, critics called for the cancellation of MBC's Omar, which looks at the early days of the Islamic caliph Umar Bin Al Khattab, also called Al Farooq (Farooq the Great).

But Napoleon Wel Mahrousa is a departure from typical period dramas that dwell on well-known Islamic figures. Instead, by focusing on Egypt's modern history, the series revisits what it means to be Egyptian, says Gouda.

Many of the costume and set designs were taken from Description de l'Egypte, a series of publications begun in the early 19th century, comprising illustrations and notes considered to be some of the most comprehensive sources of information on Egypt's geography, antiquities and society. The books were compiled by more than 150 French scholars, architects, scientists, mathematicians, artists and printers.

"No matter how much time passes, and how much we are exposed to the outside world, we're attached to our culture and this is something good," says Arwa. "I don't want Egyptians to lose their identity."

The show airs on Rotana at 11pm, Ennahar drama at 8pm, ART Hekayat at 12.30pm, 6.30pm and 1am, and Zaman at 2.30pm and 10pm.