“We are in the middle of one of the largest mass migrations in human history,” says Kaneza Schaal, a theatre director and performer whose play Cartography, made with Christopher Myers, was recently in rehearsals at New York University Abu Dhabi (NYUAD). “We wanted to think what tools we had as artists in this situation to make a context for young people to share stories together.”

Cartography, which premieres at the Kennedy Centre in Washington DC in January, addresses not the typical theatre-going public, but young people – many the same age as those attempting these border crossings on their own – and uses technology to draw them in.

At the recent rehearsal at NYUAD, schoolchildren from Al Raha sat neatly in attendance. For this iteration, the play was broken into two: first, a dialogue-driven performance in which three women sketched what they had fled from and their encounters along the way.

Then, secondly, the audience were asked to take out their mobile phones. The kids rustled through their backpacks and began logging into a network that was created especially for the production.

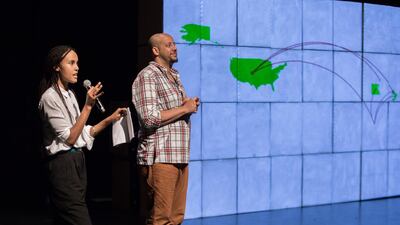

A blank screen appeared behind the performers while a map was presented on the phones. Schaal and Myers then asked the audience to trace their own journeys to Abu Dhabi and, if they wished, the countries their parents and grandparents had also moved to and from.

Zing! A couple of opening salvos were fired from the United States to the UAE. Zing! More from Europe. Whoosh! A few bounded westward from the Philippines. Some short hops came from the Levant. A few tentacles reached down to Africa. And then, as if a gate had been pushed open, a flurry of lines crossed over to Brazil, and South America revealed itself on the map. Invisible until they were activated by the audience’s journeys, soon nearly all the countries of the world appeared, until there were green continents and a tangle of routes overhead, like a pilot trailing spools of red string.

“We wanted to put these young people on a continuum,” says Myers.

“One of the myths about the refugee crisis is that it’s a new thing. This more recent alarm of the past five years ignores the fact that there have been sub-Saharan Africans migrating for many years.

“My grandfather came from Germany in 1928 on a boat and his first day in New York was spent in jail. Kaneza’s family is from Rwanda. We have so many of these refugee stories in our DNA.”

Myers and Schaal, who have collaborated before, began developing the piece after working in Munich with young refugees. Although separated by language and tradition, the children had critical experiences in common from their migrant journeys.

“There was one moment where a young woman from Syria, who was living in the same residence as someone from Nigeria, realised they had both been on inflatable rafts on the Mediterranean,” says Schaal. “There was this moment of understanding between them: you know what I am talking about.”

Cartography aims to extend this moment of understanding beyond those who are classed as refugees and out towards the audience, so many of whom have also moved and travelled, albeit under different circumstances.

“It’s such a gift to understand the world as one of migration as opposed to these hot points of tension and trauma,” says Myers. “We wanted to use theatre to create a point of contact through which people who have experienced this kind of hardship and the people who have never experienced this kind of hardship could meet and see each other.”

At NYUAD Myers and Schaal took a visible role in the rehearsal, calling out to the Raha students and joking about missteps in the process – Myers said he wanted to call the play “Why We Are Not Cats,” because cats don’t migrate – and, in a sense, to put themselves forward as role models for rethinking migration. Schaal, who directed the play, is the natural performer and has acted in the respected New York-based theatre companies The Wooster Group and the Elevator Repair Service.

Myers, who wrote the script, is a man of a unique range: he has authored award-winning children’s books, as well as plays, and is a sculptor trained on the Whitney Independent Study Programme, a crucible of critical thinking associated with the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

On stage, and in conversation, the pair have a beat-for-beat rhythm: neither talking over one another nor finishing each other’s sentences, they pause to reflect on what the other has to say.

The result in Cartography is a sui generis mix of high-brow allusions – to Homer’s The Odyssey, among others – and a politically inflected reconsideration of both theatre’s intended audience and its formal parameters.

Technology, for example, becomes not a gimmick but a way to echo elements of the refugee experience. The digitally rendered ocean projected behind the performers reacts to their voices: growing tumultuous as the drama of their stories intensifies, and calming down when their emotions quiet.

“Some of the kids had never seen water so big, and they had all this encounter with the ocean,” says Schaal. “It was seen as a threat and a fear, and we like the idea of inversing that and giving to their voices the ability to control the storm. The sea was a radical moment for all of these kids. They had to set their fate on the thin blue line of that horizon.”

The integration of mobile phones, too, relates to the way that phones were so important to the refugees on their journeys, helping them to navigate through the different countries they passed. And even once they arrived in their host country, Schaal notes, “they live in this hybrid world – from the WhatsApp messages they’re getting from home and the bomb shelters of their former schools, to the European job-training programmes that are on apps.”

Both the code for the ocean and the user-generated map were developed during Schaal and Myers’s NYUAD residency last month, where they worked with the university’s interactive multimedia team.

The NYUAD Arts Centre is a co-commissioner of the project, and as such, plays a key role in supporting its development. Schaal and Myers led workshops and readings, and staged this rehearsal for students and members of the NYUAD community – a typical process for the Arts Centre’s commissioning strand.

“One of the ways we describe the work of the Arts Centre is as a laboratory for performance,” explains Bill Bragin, executive artistic director of the NYUAD Arts Centre. “While most people understand the importance of research and experimentation as a process in science, most people don’t think about the parallel process that takes place in developing artistic work.”

For this play, with its subject of migration, Myers’s and Schaal’s time in Abu Dhabi was particularly helpful to the project. The pair looked beyond the NYUAD academic community to engage other ethnic groups on the subject of migration, including Filipina and Sri Lankan domestic workers as well as African-American converts to Islam, and added new stories to the research behind the project.

“Abu Dhabi is a harbinger of things to come globally around the idea of migration,” says Myers. “It has cemented our commitment to, A, understanding that communities need to be talking about this, and B, we need to understand it as a continuum.”

“I ate callaloo [a Jamaican dish] for iftar in Abu Dhabi,” says Myers. “Story told!”

Cartography premieres at the Kennedy Centre in Washington DC in January next year. For more information, see www.kennedy-center.org

_____________________

Read more:

This is 'Borderless' Japan's new digital art exhibition by teamLab

NYUAD study into sign language and brain function 'shows how similar people are'

Maritime history found in the coral walls of RAK ghost town

_____________________