A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, there was a planet devoid of home entertainment centres. There really was. In a land known as the 1970s, there were probably as many video recorders as there were videotapes, and those that contained pre-recorded movies were prohibitively expensive. With film rentals in their infancy, the only way to see a movie was on the television or, gasp, at an actual cinema, and often a film had come and gone by the time you had telephoned the box office.

And yet there was another way: the novelisation, or a script in a dustjacket’s clothing. A writer was hired to turn a screenplay into viable prose, fleshing out stage directions, transforming camera angles into points of view, narrating a character’s internal life and transcribing dialogue.

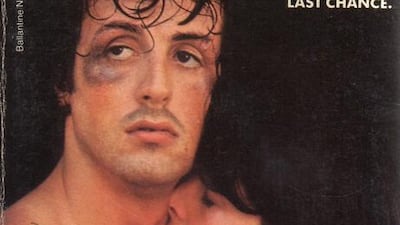

In Sylvester Stallone's Rocky II, for example, we experience Apollo Creed beating up Rocky from our hero's perspective: "We weren't fightin' for no money or for no cheers or for no newspapers; it was for something else that I don't know, it's almost religious."

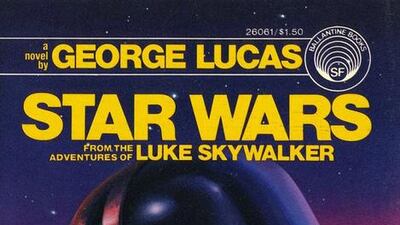

I loved novelisations as a young cinephile. Barred from seeing movies with adult certificates like Alien and Aliens, my only recourse was to read all about them in novelised adaptations by Alan Dean Foster. Arguably the Shakespeare of the medium, Foster also crammed Star Wars into a book, and has just performed the same Jedi mind trick on The Force Awakens.

Foster discussed the challenge of working on the millennium’s biggest and most secretive film. “The secrecy surrounding the project would have made the NSA [National Security Agency] proud. As the author of the novelisation, it’s like pulling teeth to get the studio to release sufficient material from which to work. Once you explain that without such material the resultant book will not match the film, it becomes easier to obtain.”

I bought the original Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker for different reasons – as part of an unquenchable thirst for any object that had the words Star or Wars, and preferably both, on them. Indeed, I raced through Foster's work with an excitement that school never inspired, begging the question: did Foster's novelisations turn me into a reader?

My collection over the years has grown surprisingly vast. Rockys II and IV – why didn't I buy III? – by none other than Sylvester Stallone. Superman III and E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, both by William Kotzwinkle. These are the tip of the iceberg.

For most critics, the presence of these works in a bookcase would be reason to burn it. Film writer Joe Queenan is not the first to call novelisers "hacks" and even compares them, with tongue a little in-cheek, to pornographers. A (positive) review of Foster's The Force Awakens in The Washington Post noted that "Snobs may dismiss such books as an attack of the clones…"

Acclaimed novelist Jonathan Coe offers a more measured, ambivalent view of "That Bastard, Misshapen Offspring of the Cinema and the Written Word": "At home, my bookshelves groan under the weight of these execrably-written texts: cheap, hastily-assembled adaptations of recent movies…".Perhaps the most famous assault on this fusion of unoriginality and commercialism comes in Woody Allen's un-novelised Manhattan – whose 1979 release coincided with the novelisation's golden age.

Mary, Diane Keaton’s jobbing journalist, is hammering away at her typewriter. “Boy, you’re really typing away in there,” observes Ike, played by Allen himself.

“It’s a cinch,” Mary replies. “I’m on that novelisation.” Ike, who thought she was reviewing ‘The Tolstoy Letters’, is as appalled as any self-respecting Woody Allen character would be: “It’s like another contemporary American phenomenon that’s truly moronic – the novelisations of movies,” he says with rising hysteria. “You’re much too brilliant for that.”

For our purposes, the most important moment arrives when Ike asks: "What do you waste your time with a novelisation for?" It's a good question to ask, of writers and readers too, of pre-video classics like Edgar Wallace's King Kong, and the post-internet resurgence of Godzilla (a bestseller for Greg Cox in 2014), Greg Keyes' Interstellar and Nancy Holder's Crimson Peak. Even Seth MacFarlane, creator of TV series Family Guy, has got in on the act with his A Million Ways to Die in the West.

Do novelisations possess any artistic merit whatsoever, or are they simply yet another wing of a modern blockbuster’s merchandising overload? Why do writers write them, and readers continue to read them?

How have they negotiated the 21st century’s ever-quickening shift from readers to watchers? And does the novelisation’s survival reveal anything about the respective forms?

So, why do people waste their time with reading movies? Speaking on behalf of authors, Mary in Manhattan says: "Because it's easy and it pays well."

Foster, who appeared at the Emirates Literature Festival in Dubai in 2013, is proud to agree. “They are perceived as being written solely for the money. In that respect, I am happy to be in the company of most of the writers who ever lived, from the Greek playwrights to the present day.”

So much for cash. Are novelisations easy? Foster says no, arguing “It’s much harder to make a book out of a movie than it is to make a movie out of a book.”

When I asked Holder about adapting Crimson Peak, the process sounded anything but stress-free. She began by researching the story and creative team responsible.

"I read and watched everything on Guillermo del Toro that I could. I bought books for which he had written forewords. I also read or watched everything that he cited as influences on Crimson Peak. I was happy to see that I knew nearly all of them, except for Uncle Silas by [J] Sheridan Le Fanu."

Holder was then sent the screenplay along with a style guide. “I began to annotate the script with coloured tabs to keep track of points of view. I practically memorised the script.”

Finally, she travelled 230 miles from her home in San Diego to a screening in Los Angeles, taking notes along the way. Only then did she start work, fusing del Toro’s vision with her own.

“I added the inner thoughts and asides of the characters. I was very happy that I was allowed to add a lot of backstory and a few scenes that weren’t in the script. That was a real joy.”

Something in this engages in a genuine argument about originality and the curious relationship between page and screen. If Holder were a screenwriter adapting a novel, her comments about artistic fidelity and interpretation would probably not inspire the sort of sardonic dismissal voiced by Queenan. After all, books regularly make Oscar-winning movies – from Gone with the Wind to The English Patient to 12 Years a Slave. There is an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay, most often honouring an adapted work of fiction. We have no problem with Graham Greene writing a novella of The Third Man as preparation for the screenplay.

What is so unsettling when this relationship is reversed? Is it because the inversion exposes assumptions about perceived hierarchies between fiction and film, art and commerce? Are novels considered too good to bother themselves with trashy movies, excepting those occasions when a well-heeled film producer comes knocking at a writer’s door?

The subtext – that wealthy, vulgar nouveaus are patronising the real literary talent – feels like a hangover from Hollywood’s dastardly seduction of F Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner.

As Woody Allen hinted, some of the distaste centres on the writers who tend to do the novelising and the types of films chosen to be novelised. Neither Citizen Kane or The Seventh Seal has been turned into fiction.

True, Jean-Luc Godard's Vivre Sa Vie inspired the academic Jan Baetens to attempt a serious fictional version. In 1920, Jack London produced a novelisation of Hearts of Three, based on Charles Goddard's script. But both are high-end exceptions. Don DeLillo, sadly, has still not attempted that long-awaited novel of American Pie 2.

David Morrell created John Rambo in his 1972 novel First Blood and novelised both sequels. He was sceptical about adapting Rambo II. "The script was 86 pages and had lines like 'Rambo jumps up and shoots this guy. Rambo jumps up and shoots another guy.' To novelise it, I had to add a lot of other material."

In his introduction to Rambo II, Morrell captures a fundamental challenge of the novelisation. The movie's climactic scene features Rambo piloting a helicopter and using "machine guns and rocket launchers to blow the s..t out of everything". His impact onscreen is enhanced by Stallone's gurning muscles, by Jerry Goldsmith's musical score, and a deafening sequence of sound effects that Morrell summarises as "BLAM!"

Foster is not fazed by the thought of transferring high-octane drama to the screen.

“Visuals and big set pieces are easy to do: you simply describe what you are seeing on screen, or what you imagine will appear. Without actually seeing the film, that can get tricky.”

Morrell’s prose version seems to betray his initial hesitation. “[Rambo] flattened, annihilated, obliterated the barracks on the left, where he himself had been held years earlier. Yes! And he kept shooting, couldn’t stop himself, the dragon roaring, razing another guard post, blowing apart another truck.”

Beneath the bravado one can detect a certain desperation to match the movie’s visual and sonic ultraviolence.

The quotation contains no less than three paragraphs: that “Yes!” exclaims alone. The parade of repetition, italicisation and exclamation parodies an action movie’s unsubtle overload – orchestra plus pecs plus BLAM equal thrills – but without the visceral punch.

One could summarise Morrell's challenge as the chasm between show-and-tell. Novels by their very nature can only tell, unless they add pictures, as was standard a century-and-a-half ago. Movies can do whatever they want. Take Foster's description in The Force Awakens of a lightsaber "flaring to life, a barely stable crimson shaft notable for smaller projections at the hilt: a killer's weapon, an executioner's fetish of choice".

Compared to the thrum and glow of the real thing, this is ponderous and also oddly comic. And yet, novelisations continue to prosper. Cox alone has hit recent bestseller lists with Godzilla, Man of Steel, Underworld, Ghost Rider and The Dark Knight Rises.

The whiff of the cash-in is inescapable, but so too are more positive aromas. Even now, the suspicion lingers that fiction ennobles cinema in much the same way that obscure British stage actors lend class to US$200 million (Dh735m) comic book epics.

It is often said that second-rate books make the best movies. Turning this on its head, only the biggest, most successful movies deserve being turned into books.

Part of the reason why novelisations were invented in the first place was to lend gravitas to an embryonic and much-derided popular art form. The novel's potential to elevate as well as advertise cinema was overt when Wallace wrote a novelisation of King Kong shortly after finishing the screenplay. Producer Merian C Cooper saw the advantages of publicising a film "based on the novel by Edgar Wallace".

Similar tangled tales of art and money enveloped Erich Segal's Love Story and Peter George's Red Alert, which he novelised as Dr Strangelove after Stanley Kubrick had his way with the text.

Foster says the modern novelisation hasn't changed, at least from the writer's perspective. "It's still a matter of getting inside the heads of the characters, relaying their thoughts as you perceive them, and describing their surroundings." Nevertheless, judging by the reaction to The Force Awakens, today's novelisations are read with a different kind of awe. The sense that the fiction bestows straightforward credibility has been replaced by the idea that it continues and expands – if not deepens – our relationship with beloved characters.

“The primary reason people bought novelisations [in the 1970s] was to re-experience the film,” says Morrell. “Novelisations eventually morphed into books that used characters from a film or a TV series but that featured new plots.”

In a post-Big Bang Theory world, reviews of Foster’s new book are filled with exhaustive comparisons of film and text. The fanatical website Denofgeek is convinced that Foster has vouchsafed various Force-altering secrets, including a deleted scene involving Chewbacca ripping the arm off a chap called Plutt.

Such an evolution acknowledges a fundamental objection exemplified by the novelisation: that readers know the story, including its twists and ending, in advance.

Putting aside the counterargument that this doesn't stop us watching Hamlet or 50 Shades of Grey, I am possibly the only person on this planet to have read The Force Awakens without seeing the film. When I mentioned this to a friend, he looked on with horror and blubbered about spoilers.

But, I replied, why wouldn't the film spoil Foster's novel? My friend called me an idiot and I didn't disagree. But the novelisation, like Star Wars itself, has moved on and become something new, different and – whisper it – fun. If only DeLillo would get cracking.

James Kidd is a freelance reviewer based in London.