The expression on the faces of crowds of people gathered on the banks of the River Seine perhaps said it all: disbelief, horror, sadness at the sight of one of France’s most famous monuments, battling with and seemingly overcome by flames.

It is difficult not to compare the magnitude, if not the manner, of the devastation at Notre-Dame to older and more cataclysmic episodes such as the wartime destruction of Coventry, Dresden and Cologne cathedrals, or even – in the way the event played out in the media, mesmerisingly, in real-time – to the collapse of the Twin Towers of the World Trade Centre in New York on 9/11.

Thankfully, in this case, no lives were lost, but in each disaster, the fate of more than a piece of architecture or the signifier of a city was at stake. It was the permanence and resilience of civilisation that appeared to be illusory as yet another act of trauma was visited, not just on a site of world heritage, but on the global psyche. "Notre-Dame, a world monument, a French sentiment, went through the pain of fire last night," the former president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, wrote on Twitter, the morning after the blaze. "I felt as sad as when the Buddhas of Bamyan were destroyed."

While Pope Francis and the Grand Imam of Al Azhar mosque in Cairo also used Twitter to express their support, Jean-Claude Juncker, president of the EU Commission, was one of many who likened the event to a bereavement. "We are widowed, to a degree, all of us," he Tweeted, of the fire that "struck at the heart of everybody who has visited Notre-Dame. Europe has been hurt, France has been hurt, Paris has been hurt."

Speaking only a few hours after leaving the cathedral, where he had been working with fire crews to help save its treasures throughout the night, senior French architect Pierre-Antoine Gatier echoed Junker's comments. "We are discovering that this is more than a personal relationship. It is a shared feeling. It is like a person, a lady in the centre of Paris," the heritage expert told the BBC. "We couldn't imagine that it would be so fragile. It has been the centre of Paris since the Middle Ages and we couldn't have imagined that it would not exist forever."

'It will not be the same'

An expert in historic conservation with responsibility for the monuments in Paris's 5th arrondissement, Gatier was already focused on the future and the manner of Notre-Dame's rehabilitation, an issue of restoration rather than reproduction, he insisted, that will be freighted with nuanced discussions of authenticity. "Each time there is destruction, we have to think about what kind of decision we want to make," the architect explained. "Each time we do something to a historical structure we change it. It will not be the same. Even though our dream is to respect the cathedral and to recreate it exactly as it was, it will be something different," he added.

The restoration of all monuments is fraught with difficulties, especially in the case of a complex building such as Notre-Dame, which, although it is described as medieval, is actually the result of centuries of architectural accretion and change, much of which occurred between 1843 and 1864 under the guidance of the pioneering architect, theorist and medievalist Eugene Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.

A titanic figure in the cultural history of 19th-century France, Viollet-le-Duc is still revered by architects and historians and continues to be a household name in France. His reputation was both made and marred by what was seen for many years as his overly enthusiastic restorations, which were publicly understood to have defaced national monuments such as the medieval walls of the city of Carcassonne, the island fortress of Le Mont Saint Michel and the Basilica of Saint-Denis.

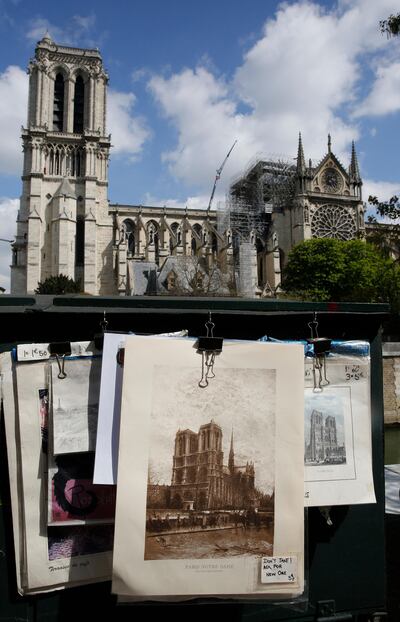

If any one moment captures the tragedy of the fire that engulfed Notre-Dame, or the scale of the reconstruction work that is required to reinstate its glory, it was the dramatic sight of the cathedral's 300-foot spire collapsing into its medieval roof, sending a plume of flames and orange smoke sprawling across the French capital. Widely regarded as Viollet-le-Duc's masterpiece, the spire was a famed part of the Parisian skyline, but like so much of Notre-Dame it was also a confection of the architect's learned imagination, a 19th-century construction for which little or no medieval evidence exists.

"What you would have seen, if you had gone to Notre-Dame [the day before the fire], was essentially a 19th-century cathedral," explains professor Martin Bressani, an architectural historian and director of the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University in Canada and author of Viollet-le-Duc's intellectual biography. "It still remains a medieval building, because it wasn't rebuilt from the ground up, but a lot of the texture, the articulations, all of the sculptural work, all of the gargoyles, the famous chimeras that crown the galleries at the front, all of that is 19th-century work."

From medieval to modern

Bressani is not alone in understanding Notre-Dame as a monument in perpetual motion or in questioning the ideas that underpin the popular "picture-postcard view" of the building. In his pioneering 2009 study, The Gargoyles of Notre-Dame: Medievalism and the Monsters of Modernity, the University of Chicago art historian Michael Camille argued that the works carried out by sculptors such as the little known Victor Pyanet, working under Viollet-le-Duc's direction, were not only contemporary evocations of an imagined past, but effectively transformed a medieval masterpiece into a work of modernity.

While Bressani insists on Viollet-le-Duc's academic rigour and earnestness, refusing to dismiss him as a fantasist or as somebody who approached his work casually, he locates the architect's effort within a wider 19th-century consciousness informed by the intellectual spirit of Romanticism and a nationalism that was concerned with revitalising France's post-Napoleonic place in the world through a rediscovery of what were understood as its cultural roots in the Middle Ages.

"In some ways the building we see when we look at Notre-Dame, even the very informed person, is highly filtrated by the romanticising of the Middle Ages in the 19th century and it's very hard to escape that lens," Camille suggests. "To negate that [history] would be a strange thing to do, but the opportunity in the sadness and the disaster of this catastrophe opens the question, what do we do next?" Emmanuel Macron, President of the French Republic, spoke on television in the immediate aftermath of the fire. "We are a people of builders. We have so much to rebuild and we will rebuild – we will make it even more beautiful than before," he insisted. Promising to reconstruct Notre-Dame within five years, Macron referred to the rehabilitation effort on Twitter as a matter of "French destiny".

A moment of opportunity

Irish architect Niall McCullough, co-founder of Dublin's McCullough Mulvin Architects, points to recent major rehabilitation projects, such as Foster + Partners' design for the Reichstag and David Chipperfield Architects' two-decade-long restoration of the historic Neues Museum, both in Berlin, both of which pay homage to the crises that shaped those buildings' histories. He sees the Notre-Dame fire as a moment of opportunity. "How do you find some way of exploring the layers of ageing in Notre-Dame, or the quality of materials or what you might find under the 19th-century surfaces?" says McCullough, whose recent conversion of St Mary's Church in Kilkenny, Ireland, has been shortlisted for this year's European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture – Mies van der Rohe Award.

For McCullough, far wider historical and social forces are at stake when it comes to the renovation of historic buildings such as Notre-Dame, forces that are intimately connected to our notions of the ideal, a factor that was just as important for Viollet-le-Duc as it is for contemporary architects. “Viollet-le-Duc was always consistently well-informed about what he was trying to do, but he also invented, to bring the building back to some perfect image of what he was searching for and that’s what you’re looking at. It’s a construct,” he explains. “But the ideal is no longer a simple purity or an abstraction, the ideal now is something that is layered and more complex, that accepts age and the patterns that others have contributed.”

McCullough believes a contemporary notion of the ideal, rather than factors driven by more grounded archaeological and historical realities, will ultimately determine the form that the rehabilitated Notre-Dame will take. Whether or not the restoration allows room for the memory of the recent fire remains to be seen, but what is certain is that the result will be forged by the political realities of the present, involving as partial an approach to history as those pursued in each of the previous episodes in the cathedral's tumultuous 856-year past.