Near the entrance to the vaccination tent within the ungainly sprawl of the migrants’ camp at the French port of Calais, Mohammed Shafi Sedeguy gathers his six children around him in a huddle.

Calais is a long way from the dangers and deprivation he remembers of life in Afghanistan. For now, the family, also including Mohammed’s wife, Mahboba, is safe.

A team from the French charity L’Auberge des Migrants (Shelter for Migrants) found them on the road leading from the railway station, a sodden, dishevelled group walking in the pouring rain. “We got them into a hotel for a few nights until a tent with heating was available at the camp,” says volunteer Rachel Hunter.

The ability of charities and NGOs to deal with basic needs is vital, especially as winter arrives in northern France. At least the Sedeguys are out of the cold and rain. But day-to-day life at what the media – and some of the migrants themselves – call The Jungle remains blighted by dirt, discomfort and insecurity.

Hands International, which runs the vaccination programme, can protect the family against influenza and direct them towards the Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) tent for other medical care. There is local support, too.

From the days of the Sangatte migrants’ shelter at Calais – the Red Cross camp that opened in 1999 but which became hopelessly overcrowded and was closed by the French government three years later – Calais volunteers have kept up a constant supply of food, clothing, bedding and other essentials.

But none of this gets close to a real answer for Mohammed, a 44-year-old lorry driver, Mahboba, 42, and their children aged 10 months to 12 years.

Not far from the camp, there are cars, coaches, lorries and foot passengers heading for trains or ferries bound for the UK. Eurostar expresses from Brussels and Paris slow down to enter the Channel Tunnel. And the reason the Sedeguys are living rough in this drab French port and not back in Afghanistan’s third largest city, Mazar-i-Sharif, is that they long to make that crossing, too. They want to be in Glagsow, where several relatives have been able to make new lives. But Scotland, at the moment, feels as remote as the Moon.

Would they have been better off staying in Afghanistan? “Too much trouble from government and Taliban,” Mohammed mutters vaguely.

Amid the intermittent squalor of the camp, there is a curious semblance of structured society, as witnessed by a support system that includes the presence of doctors, nurses, educators and a range of volunteers – qualified or just able to lend a hand where needed.

Each morning, lorries squeeze through the camp in order to empty and clean the rows of portable toilets. Migrants wash at standpipes and clean their clothing and boots. Layers of hardcore gravel enable the narrow road through the camp to resist the worst effects of downpours, though heavy rain can still reduce the ground around accommodation tents to a mudbath.

In makeshift classrooms, children – and some of their parents – can learn elementary French or English. Visiting well-wishers, fact-finding groups and the media are welcomed with expectant smiles from people who have fled poverty and hopelessness, persecution and conflict. The flags of their different countries fly from poles rising above the shops and restaurants run by the more resourceful. There are information tents, power lines, barber shops, a library, mosques and a Christian church. There is even a theatre.

The Afghans seem the most methodical, and also the dominant group. There are also many Syrians as well as Iraqis, Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Eritreans, Egyptians and Sudanese.

The migrants are grateful for what is done each day for them and for the procession of individual donors who bring warm clothing and bedding to the camp. But they want no sense of permanence, sharing instead a single aim: to make the geographically-short, realistically-huge leap from France to the UK.

With more arriving each day, the numbers now vary from official figures of about 4,500 to upper estimates of 7,000, at either end of the range forming what French television recently called “Europe’s biggest slum”.

Home means whatever comfort and warmth can be found in a cramped array of tents and thin wooden slats covered by blue tarpaulin.

Some, especially those housing women and children, now have heating provided by the French authorities after rising concern that winter would significantly worsen the already grim conditions and threaten health. But the overwhelming majority of people stuck at this staging post of humanity on the move are, or appear to be, male.

Complete family groups like the Sedeguys aremore unusual. But the goal of reaching the UK, described witheringly by French commentators and politicians as an Eldorado of benefits supplemented by a flourishing black economy, is common to all. Or almost all. A handful – disillusioned by months of waiting to complete the final leg of a journey that has taken them through deserts or over mountains, across perilous seas and halfway through the continent of Europe – now wonder whether they should ask to stay in France or try their luck in Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands or Scandinavia.

Officials report more applications for asylum on France, encouraged by comments from the French interior minister, Bernard Cazeneuve. But it is a trickle. Many, perhaps most, migrants have some English but few have even basic French. Many have, or claim to have family connections in the UK and few are enamoured of France’s formidable red tape. Yet the dream that drew them to Calais is looking increasingly elusive and recent events threaten to crush their hopes completely.

First, the sheer numbers of people – 800,000 this year alone - pouring into Europe’s southern points of entry, notably Greece, mean the camp has ceased to be the only front line in the continent’s escalating migrant crisis. Migration has become a much broader issue. While many have undoubtedly fled for their lives from war zones, other are simply seeking better lives. Europe does not want economic migrants and the hostility of Hungary demonstrates that not all European countries want genuine refugees.

Even Germany, willing at the outset of the crisis to accept large numbers of those making the slog through Greece and the Balkans, has become less welcoming as thousands continue to arrive daily despite Chancellor Angela Merkel’s insistence that all is under control. The emphasis has switched from resettlement to prevention, action against the people smugglers and eventual repatriation for most migrants.

Britain in particular has set itself against accepting more than a token figure – 20,000 Syrian refugees by 2020 – though civil war has already driven up to two million out of the country, almost half of them into neighbouring Turkey. If there is only limited sympathy for Syrians, what chance do Afghans, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis stand?

Mohammed Sedeguy says his parents, three sisters and a brother who settled in Glasgow, along with two of his wife’s sisters, are now British citizens. But with stricter security, including 1.8 kilometres of new metal fencing, five metres high and topped with razor wire, to protect the port, even the younger migrants unencumbered by families are finding it harder to sneak across.

No one knows quite how many have made it through, though it was recently estimated that more than 1,500 attempts had been made to enter the tunnel. Several migrants – at least 20 this year according to Calais Migrant Solidarity activists – have died after being run over by cars or trucks, or electrocuted after climbing on top of trains.

Secondly, some migrants have done the collective cause serious harm with outbreaks of disorder, often incited by far-left or anarchist groups, which have brought clashes with French police, blockades of the tunnel and port, and damage to the homes of people living nearby.

Among residents of the Rue de Gravelines, previous sympathy for those in the camp is wearing thin. Many have been generous with gifts of shoes, clothing and blankets. But attitudes hardened after three successive nights of violence in the street last month, as migrants vented their frustration at the authorities' tougher measures to keep them away from Channel traffic. They pelted police with stones and other projectiles, though some told The National this happened only after they were tear-gassed.

“Fed up, fed up, fed up,” one resident told France 3 television. Another pointed to broken fencing and garden furniture. The Calais mayor, Natacha Bouchart, urged the government to send in troops to reinforce stretched police resources and even said families might have to be moved out. And thirdly, there was Paris.

Politicians have claimed at least two of the ISIL attackers who left 130 dead in the capital on Friday, November 13, may have slipped into Europe posing as refugees from the Syrian conflict.

“Some people have been saying for a long time there [are] jihadists among the migrants at the camp and no one believed them,” says Marion Lefebvre, an English woman who has lived in Calais for 30 years and is a former president of the town’s branch of the Agora women’s charity.

There is no evidence that those suspicions are well-founded. Indeed, the suggestion that ISIL might encourage actual or would-be terrorists to live among thousands of migrants while preparing for attacks seems far-fetched.

Allegations that not all the passengers stepping from people smugglers’ boats are truly refugees remain unproven but have dramatically altered perceptions. Vehemently anti-immigration views are no longer restricted to Europe’s unpleasant far-right parties but embraced by mainstream politicians.

All of this is hard on the migrants whose hazardous odysseys from troubled homelands – and the striking determination and ingenuity they have drawn upon to stay alive and focused – show them to be potential assets to any society.

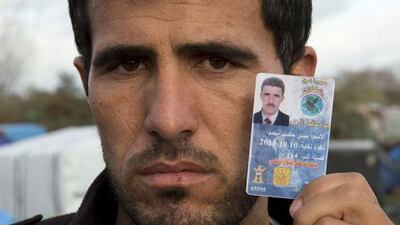

Hassan Mohammed, 29, also has a sister in the UK. He waves his identity card from Iraq’s counter-terrorist police in Fallujah, with whom he served, before ISIL and anti-government militia seized large areas of the city from early last year. He has been in Calais for seven months and begs the British government to give him a chance.

“I can make a good life in the UK,” he says. If he cannot get there legitimately, he says he will try to smuggle himself across. “One day, I will succeed,” he says.

Omar Waheed, a Pakistani of Afghan origin, says he is 14 and reached France after months on the road through Iran, Turkey, Serbia, Bulgaria, Austria and Germany.

“School was too expensive,” he says. “I want to start my education in England. And I want to play cricket again – I am a good batsman.”

At one of the shops, another Afghan, Mohammed Omar, in his 30s, shakes his “till”, a bucket containing a few notes and coins. “Maybe 30 or 40 euros,” he says.

He buys his stock – biscuits, confectionery, soft drinks, cooking oils and a few pairs of boots and shoes – from a supermarket, adding a little to the prices to give a small profit margin. Net earnings, shared with a fellow migrant, amount to seven or eight euros a day. A father of five, he worked for his local council in Paktia province. He rolls up a trouser leg to show a bullet wound.

“The Taliban shot me for going to work,” he says. “There was nothing left for me and my family. No education, no work, no life.”

Then there is the scar on his arm, from one of his attempts to jump onto a lorry heading for the UK.

“I have been here two months and tried all the different ways of getting over to England, maybe 10 to 15 times and I’ll keep on trying until I get there. Then I hope my family can join me.” Father Chris Vipers, a Catholic priest visiting the camp from London with an inter-faith group that includes Muslims and Jews, is impressed by the self-help and comradeship.

“They are all looking after each other, making sure life goes on,” he says. “But there should be no need for a camp like this. What we want to do is get a message back home, loud and clear, that this cannot go on. There has to be a better way. People should not be robbed of their dignity. If I ruled the world, places like this would not exist.” But like so many offering solidarity, Fr Vipers does not pretend to have the answers to an immense human problem. Should Britain and France, the rest of Europe, or even the countries of the Arabian Gulf be doing more? “That’s not my decision,” he says flatly. The lack of political will leaves the migrants feeling impatient and powerless. Many are prepared to do whatever is needed to outwit French and British officialdom and cross the narrow stretch of water to the UK.

Methods adapt to each new crackdown – a young French fisherman was among eight men arrested recently, accused of using a Zodiac boat to whisk migrants to England from a secluded beach near the neighbouring port of Dunkirk for up to €12,000 (Dh46,735) for each illicit passenger.

While the migrants consider their own tactics, volunteers try to offer them respite from the daily grind and grime. Close to the vaccination centre and a busy mosque, a domed white marquee houses the Good Chance theatre group, which operates with support from stage organisations.

Migrants are encouraged to take part in its productions. “We have our views, of course,” says Joe Murphy, a playwright and one of the founders. “But we are here for humanitarian, not political reasons, to offer relief in an expressive form for struggling people.” Why choose Good Chance as the name? “We adopted it from the migrants’ own experiences,” he says. “Each day is seen as either a ‘good chance’ or ‘no chance’ day for getting across the Channel. In a desperate situation, we hope the theatre provides a different kind of good chance.”

Colin Randall is a former executive editor of The National.