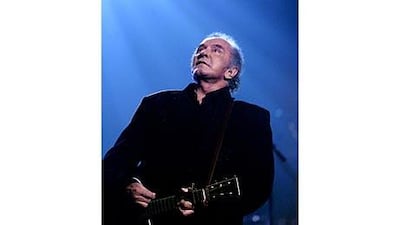

Which would you reach for first, Johnny Cash's American Recordings or Live at San Quentin? Bob Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited or Time Out of Mind? The Rolling Stones' Aftermath or Tattoo You? The question stares you in the face on the sleeve of the new Johnny Cash album, American VI: Ain't No Grave, his final studio recordings, due to be released Friday, some seven years after they were set to tape. The front cover shot is of the Man in Black as a snaggletoothed boy with a lopsided grin and a searing stare. On the back is a picture of the same face - showing the same intensity of gaze, but aged beyond repair - staring from behind a pane of glass.

Talking soon after Cash's death in September 2003, the producer Rick Rubin revealed, even then, that "there may be a sixth disc because I found a whole other batch of tapes. It came as a surprise at the last minute - songs we had worked on four, five months ago, when we started the new project [American V]." At the time, Rubin had just concluded the mixes on the Unearthed boxed set of session outtakes. He sent them to the singer on September 11, 2003. Cash died the next day, before that final package of recordings arrived in the mail.

"It was a new kind of gospel album for him to do," Rubin said of the newly-discovered last recordings, "heavy, old blues-type things like Ain't No Grave Gonna Hold My Body Down." Cash's late-career resurrection has been almost universally applauded since it kicked off in 1994, and the same late-career formulae has since been applied to musical seniors ranging from Kris Kristofferson to Neil Diamond - the most recent veteran to be reinvigorated by the Rubin treatment with his 12 Songs album. Along with Daniel Lanois's woozy, atmospheric productions for Dylan, Emmylou Harris and Willie Nelson in the 1990s, Rubin's American Recordings label spearheaded a new cult of authenticity rooted in age, posterity and maturity.

The opposite has usually been the case in pop music. Until the 1990s, only blues singers such as John Lee Hooker were allowed to grow old with dignity and power. Then came the first mature "comeback" albums in rock, with Dylan's Oh Mercy and Lou Reed's New York returning critical favour to widely perceived has-beens. Dylan's early-Nineties albums Good as I Been to You and World Gone Wrong extended the age gap with cracked, solo acoustic recordings that show the mature artist reflecting on his roots and sources, and enveloping them entirely. The albums slipped out virtually unnoticed at the time, but on them, Dylan stepped from the undergrowth of his 1960s legend and forged a path to the late, great album cycle that began with Time Out of Mind in 1997 and continues through last year's Together Through Life.

Rubin's reinvention of Cash began in 1994 with the album American Recordings, made in the singer's living room with just his voice and guitar. At the time, he had been dropped by the major labels, and, like his country contemporaries, was no longer getting airplay. Members of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers joined the sessions for 1996's Unchained, and they were there during the last recordings in 2003 before the ailing Cash's death. The first posthumous album from those sessions, A Hundred Highways, was released in 2006, and now we have the final, sixth instalment. It features 10 tracks, led by the telling title track. Most of them are sharecropper-lean, spare of sheen or ornamentation.

The album clocks in at just over half an hour, and the songs come from Cash's old friends: his fellow Highwayman Kristofferson's For the Good Times; Hank Snow's I Don't Hurt Anymore; Red Hayes' gospel classic Satisfied Mind and the Sons of the Pioneers' Cool Water. A late-period original, the sternly titled I Corinthians 15:55 - death, where is thy sting? - provides the focal point of this last album's meditation on death, loss, frailty, faith and pride. It contains small words with long shadows, but no shadows longer than Cash's own.

The allure of the final works of great artists is a powerful one across all genres. The late quartets of Beethoven, the extraordinarily expressionism of Titian's last, unfinished paintings, Picasso's violently compelling octogenarian canvases, or the bravura pointillist cutting of Orson Welles' F For Fake - each has the profound allure of the last testament and final act, with all the elements of greatness at their most pronounced. It is where they are most themselves, working on their own terms, by their own rules. In their last works they are revealed.

But is this really the case with the American Recordings? Dylan expressed his doubts during an interview for Rolling Stone in 2009. "I tell people if they are interested that they should listen to Johnny on his Sun records and reject all that notorious low-grade stuff he did in his later years. It can't hold a candlelight to the frightening depth of the man that you hear on his early records. That's the only way he should be remembered."

Likewise, Mark E Smith, the frontman behind The Fall, has little time for the pieties of Cash as grand old man of Americana. "I find it horrible they way they've made money out of him releasing all these maudlin recordings," Smith wrote in his autobiographical Renegade, published in 2008. "Give me early Cash any day." Timed to appear on what would have been Cash's 78th birthday, American VI: Ain't No Grave is inevitably poignant and, yes, sentimental. Like 2006's A Hundred Highways, it features original tracks made in the last months of the singer's life at the Cash Cabin Studio in Henderson, Tennessee, taken up and finished off with the Heartbreakers Benmont Tench and Mike Campbell, the guitarist Smokey Hormel and the banjo player Scott Avett at Rubin's Akademie Mathematique of Philosophical Sound Research in Los Angeles.

When the producer Alan Douglas released late-period recordings by Jimi Hendrix featuring musicians who had never even met the man, the critical uproar was universal. Rubin has undoubtedly been more sensitive with his artist's legacy, as most of the sidemen on these final recordings had worked with Cash from the second album of the series. The music released before his death exhibits an aged, majestic maturity of purpose and engagement, with the singer calling the tunes, but these last posthumous records are inevitably Rubin's conception of what late Cash should sound like, without the singer's final nod of approval. Cash is not so much a singer here as a character in a drama, written by others.

You can't imagine either Dylan or Smith altering their opinion on the strength of the final, frail performances on American VI, but for many fans - especially those who came to Cash in the 1990s - it will be akin to a last will and musical testament, his voice carrying the golden age of American music with it as it passes from the room. Back in Victorian England, death portraits were big business. Photographers would dress the set as meticulously as a modern-day art director on a fashion shoot. Is Ain't No Grave, with the young boy and old man folded into its cover, and songs of death and reckoning, taking the idea of "ripeness is all" a little too close to Victorian morbidity?

Some fans prefer their elders to rage against the dying of the light à la Jerry Lee Lewis, the ever-restless Dylan or the late Picasso. When Welles set about making his last, unfinished and still-unscreened movie, The Other Side of the Wind, he surrounded himself with a young crew and delivered a wildly experimental movie, the fast, fractal cutting of which was like nothing seen before. Whereas the late work of Welles, Dylan or Picasso probes and disrupts our expectations, does the Ain't No Grave simply fulfil them? Are we being manipulated into a ready-cooked response?

"He was the north star. You could guide your ship by him," Dylan wrote of Cash soon after he died, and perhaps the power of these last recordings is in the singularity of purpose of the listener as much as the artist. This is music with which to navigate your own mortality. The piper had been paid in full, and if you didn't like the tune he played, you could move on. Dylan, Smith and the Man in Black would probably agree on that one.

American VI: Ain't No Grave is released by American Recordings / Lost Highway on Friday.