Lyor Cohen’s message to the regional music scene is clear: don’t remix your sound to fit western expectations. The global head of music at YouTube says artists who travel are the ones who move outward with conviction, not compromise. “They should have a zero apologetic point of view,” he says. “Let those tribal beats flow and do things that have unique clarity from the heart of an Arab person.”

It’s advice built on over a four-decade career through which Cohen, 66, was seemingly a few beats ahead of the industry. From being one of the drivers to take hip-hop beyond New York and transform it into a global juggernaut, to his current role at YouTube, Cohen's career unfolded alongside the shifts that reshaped modern music.

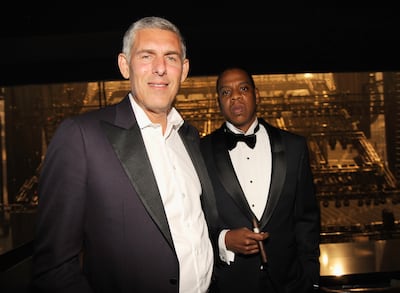

That said, the man credited with signing then-unheralded acts Run-DMC and Jay-Z to their first major record deals baulks at the suggestion that he is some kind of music industry Nostradamus.

“I respectfully disagree with that because I have never forecast anything when it comes to music in my life,” he tells The National. “I think it’s very arrogant to try to be like a weatherman detecting the future. What I do is show up where I think something is happening.

“By showing up, I can hear things, see things and observe things,” he continues. “Like going to Nigeria nine years ago and coming back with a clear sense of the rhythms and the possibilities. Or going to Korea, or to Puerto Rico and Latin America, and getting a sense of the melodies and the ambition of the region.”

That instinct for research and discovery recently brought Cohen to Riyadh, Dubai and Abu Dhabi, where he met artists and producers, and visited studios to understand what is unfolding across the Gulf. Cohen is encouraged, but he believes conviction must match infrastructure.

“There’s a real opportunity depending on the region’s ambition because I think one could actually feed their family singing only in Arabic and only going around the region, and being very popular and strong.”

Cohen’s assessment rests on scale. He now oversees music strategy for YouTube, a platform he believes is central to how audiences in the Middle East and North Africa discover and engage with artists.

“Certainly when you have two-plus billion daily active users, and many of them are absolute diehard music aficionados and fans, it’s obvious that the Levant has an enormous diaspora out there, similar to Africa, India and Latin America. There’s a vibrant diaspora that they could connect to and activate.”

The numbers in the region suggest that connection is already being made. According to YouTube’s Mena trends report for 2025, Khatya by Bessan Ismail and Fouad Jned became the most viewed song in the region with 339 million views. Saad Lamjarred’s Lm3allem continues to hold more than 1.2 billion views, one of the highest for an Arabic-language track on the platform. Abo Rany, broadcasting daily life from Gaza, secured 8.6 million subscribers and became the second most subscribed creator globally.

Cohen sees a familiar arc developing in the region, similar to what unfolded in Latin America and Puerto Rico, the latter reaching a visible peak with Bad Bunny’s recent Super Bowl performance, which generated more than 75 million streams on YouTube Music.

For Cohen, that performance reinforces a lesson he has observed repeatedly.

“When rap went global, its artists didn’t [care] about New York and made it their own – their own beats, their own stories, their own flavour,” he says. “And so what I would say to the region is that they should let those local beats flow and do things from the heart and that have unique clarity.”

As for the current debate around artificial intelligence and its role in reshaping the music industry, Cohen says it should be viewed as an opportunity rather than with trepidation. It does not strike him as fundamentally different from previous industry resets he has navigated.

“My career has always leapfrogged forward during noisy transitional times when most of the industry gets frozen in fear,” he says. “Anybody who doesn’t ask how AI is going to affect their ability to feed their family is not thinking properly. There is no stopping this. Why would anybody want to stop another tool and opportunity to help you with your craft?”

Even if technology can provide greater access, it presents its own set of challenges.

“With the lowering of the friction of entry, the democratisation of content has its good things,” he says. “But it also has its bad things, like what kids are experiencing now – a tidal wave of choice that makes it very hard to discover the music of their youth. It’s tough.”

In that environment, he believes platforms such as YouTube Music, where songs sit alongside music videos and short-form clips, give artists more control over how their work is framed and understood.

“I would say the video is a way for you to continue to contextualise and storytell and help cut through that clutter,” he says. “Video is even more critical to what I consider the long-term success of an artist. Shooting a premium music video, or the new version of what premium music videos would look like, is an incredibly powerful tool to contextualise a song and build that root system.”

It’s another lesson from his hip-hop roots. “When something is authentic, it travels,” he says. “It doesn’t have to ask for permission or water itself down. When it carries its own rhythm, its own story and its own point of view, people feel that.”