As even the most blinkered Rolling Stones or Beatles fans must begrudgingly admit, live albums can be a massive let-down. Even the greatest bands have seen their mighty oeuvres sullied by underwhelming concert recordings.

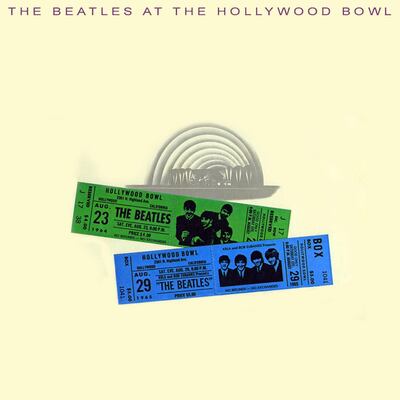

Some, such as The Beatles' Live at the Hollywood Bowl (1977), emerged after they split and should have been left on the shelf.

Others, notably the Rolling Stones' Love You Live (also 1977), signalled the end of a creative heyday. Such high-profile disappointments have created something of a stigma around the live album. But when they work, concert recordings can bottle magic.

With that in mind, one start-up intends to launch hundreds of new ones. Exit (Live) is a new online concert streaming platform created by the music producer Giorgio Serra, who came up with the concept “while living on the Indonesian island of Lombok for two years, and generally being cut off from everything”.

“One of my favourite bands was going on a new tour and it was impossible for me to go,” he tells me.

So, inspired, he “started planning to build a platform that could take me there; bring the show to me”.

The development raises the question do we actually need an avalanche of new live albums, given their patchy history?

Serra is clearly an enthusiast rather than just an entrepreneur, in fairness, and cites several favourites, that “capture a moment in history”.

“The Rolling Stones in Belgium, 1973; Jimi Hendrix at the Isle of Wight [festival]. Bob Dylan at the Royal Albert Hall… ” he could go on and on.

Some of music's most memorable moments may have been forgotten without being recorded on live records, sometimes surreptitiously. That Bob Dylan, Live 1966 LP is particularly interesting: initially a bootleg recording, it captures the contentious period when Dylan switched from folk to electric guitar, and is as famous for the furious heckles as the music.

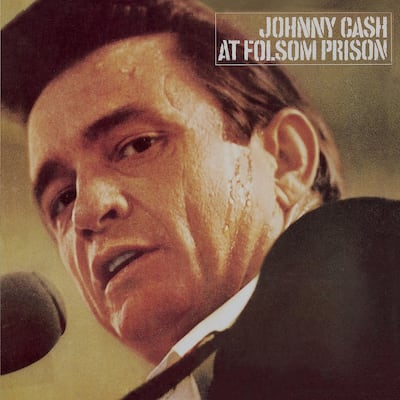

On a truly great live record, those unique elements become legendary. One of the most memorable audience responses is during Johnny Cash's rendition of the song Folsom Prison Blues during his concert at the eponymous prison (1968). Cash's captive audience are surprisingly unmoved when he first mentions Folsom, but whoop and whistle the line "I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die". It's a remarkable moment.

Audience enthusiasm can also ruin a landmark recording, however. The Beatles' aforementioned Live at the Hollywood Bowl belatedly emerged 13 years after the concerts it captured. Their esteemed producer George Martin was asked to fashion a releasable version, but clearly struggled: the album's most significant sound is shrieking girls.

It is tempting to assume that record companies are the main drivers of concert recordings, for a between-

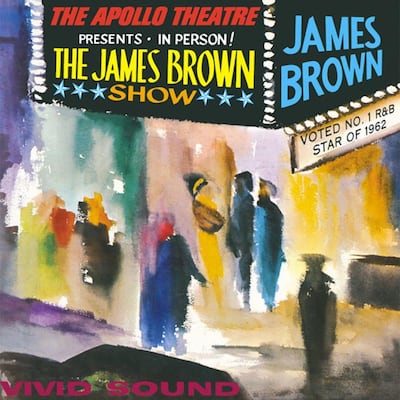

album payday, but the live-album story is often more interesting. James Brown self-funded the classic 1963 album Live at the Apollo because his label vetoed it, wrongly thinking it would flop. Perhaps their lack of enthusiasm gave his performance extra energy that evening.

Exit (Live)’s system follows Brown’s path, but cuts out the labels, and will allow bands to release recordings directly through the site. The idea is really an extension of the illicit tapes that often emerge after shows, but hopefully with better sound, as a decent digital recording can now be made relatively cheaply. “I like to say ‘bootlegs but better’,” says Serra.

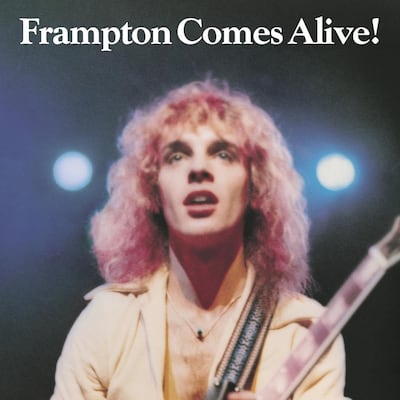

Sometimes live versions sound better than the originals. One of the 1970s' biggest albums was Peter Frampton's breakthrough Frampton Comes Alive! featuring songs that had flopped as studio versions. Sometimes, recording studios just cannot do justice to an act's onstage energy. Detroit rockers The MC5 decided to record their 1969 debut album, Kick Out the Jams, onstage, and helped to kick-start underground rock.

Such an impact relies on a fine performance, of course, which is where the Stones' more recent live records falter. The double LP Love You Live is particularly infamous as it reveals a band already becoming their own

tribute act, ploughing through old songs with less vigour than those studio originals.

Much edgier is the live work of Neil Young, the ragged king of the concert album, whose live back-catalogue is a treasure trove for newer fans.

The actor and comedian Joz Norris, for example, is currently developing a whole stage show dedicated to the great Canadian rocker, and particularly admires Rust Never Sleeps (1979). It's the antithesis of the creaky Stones' method.

“Neil toured and did a whole bunch of brand new songs which none of his live audience had ever heard before,” says Norris. “Some of them went on to become his best-known songs ever. I think the idea of using a live album to introduce an audience to new material but in a live context is really exciting.”

You can track much of Young’s diverse career via his live records, and one night at New York’s Fillmore club in 1970 proved particularly fruitful. Young’s performance emerged on record, as did the set by his unlikely support act, jazz legend Miles Davis.

Concert records are better respected in the jazz community. That genre's improvisational ethos almost insists that performances are recorded, each being unique, particularly when great artists come together. Jazz at the Hollywood Bowl (1956) – featuring Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson – is much more satisfying than The Beatles' record there.

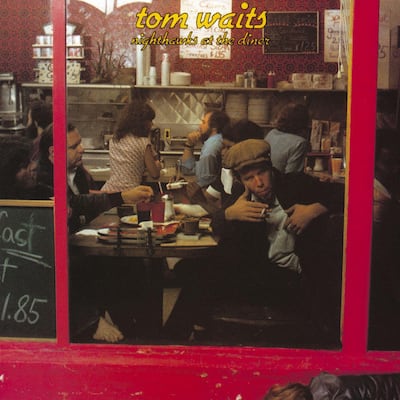

Tread carefully, though: even great live records may not always be as advertised. The aforementioned Bob Dylan bootleg, said to be from London's Royal Albert Hall, was actually recorded in Manchester. Much of U2's Under a Blood Red Sky album (1983), ostensibly recorded at Colorado's Red Rocks Amphitheatre, actually comes from shows in Boston and Germany. More contentiously, the producer of Thin Lizzy's classic LP Live and Dangerous (1978), Tony Visconti, suggested that most of that album was re-recorded in the studio – although the band denied it. A happier solution to sound issues is to actually stage concerts in a studio. Tom Waits's third album Nighthawks at the Diner (1975) was recorded at Record Plant Studios in Los Angeles, but with a small audience, in order to better capture Waits's impromptu wit: it was his most successful album yet.

Several fine live albums also emerged from the MTV Unplugged TV concert series, by REM, Neil Young, Jay-Z and, particularly, Nirvana. The stripped-down, sit-down format offered a whole new perspective on the late Kurt Cobain’s songwriting genius.

In truth, some of the greatest live records are really film soundtracks. Perhaps the most epic is The Last Waltz (1978) – a soundtrack to the Martin Scorsese concert film of the same name – which documents the final show by Bob Dylan's old backing group, The Band. Three LPs, guests such as Young, Joni Mitchell, Eric Clapton and Muddy Waters, it's an evening that had to be captured.

Also classic, but more concentrated, Talking Heads' Stop Making Sense (1984) culls just nine tracks from the US art-rockers' spectacular concert film (directed by Jonathan Demme), notably David Byrne's definitive solo version of Psycho Killer. That album is the perfect introduction to their lengthy back-catalogue.

For newer acts too, well-made live albums can work as a fine introductory best-of: you can even sneak in cover versions. Take Gavin James, the big-voiced, now jet-setting Irish singer who played a fine St Patrick's Day show in Abu Dhabi last year: his breakthrough was a cover of the Magnetic Fields' song Book of Love, from his 2014 debut album Live at Whelans.

In a music world now largely financed by concerts rather than album sales, it makes sense to work that angle. If you’re great live, let us hear it.

__________________

Read more:

Wasla Music festival offers an eclectic selection of regional acts

Egyptian indie singer and actor Maryam Saleh on her new super group

The poetic licence of Arab indie scene leader Tania Saleh

__________________