Amis & Son: Two Literary Generations

Neil Powell

Macmillan Dh147

Hovering sometimes uneasily between literary biography and critical study, Amis & Son is a highly opinionated account of two of Britain's most famous post-war writers, Kingsley Amis and his son, Martin. The elder Amis made his debut in 1954 with Lucky Jim, still one of the funniest novels of the last half-century, and published a continuous stream of novels, poems, essays and sundry non-fiction titles (books on James Bond, booze, and sci-fi) until his death in 1995. Martin emerged in the seventies and eighties with the viciously mordant satires Money and London Fields. Like his father, Martin also wrote occasional criticism and reportage, which has been collected in such volumes as The Moronic Inferno and The War Against Cliché.

Kingsley became known for his blimpish conservatism, his loathing for anything that smacked of intellectual pretension, his suspicion for faddish social trends, which he made fun of in novels like Jake's Thing (1974), where he took aim at psychoanalysis, and his contempt for anything foreign. Martin, under the influence of his literary heroes Saul Bellow and Vladimir Nabokov, fashioned a unique Transatlantic idiom that married wise- up street slang and a Dickensian obsession with grotesques to weighty conceits like the Holocaust, nuclear war, totalitarianism and terrorism.

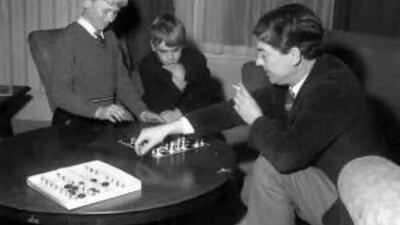

There haven't been too many father and son acts in British literary history, not that Amis & Son were exactly a family firm. There are wild stylistic divergences between the younger and older Amis: Kinsgley thought Bellow and Nabokov were rubbish, yet their relationship, which Martin wrote about tenderly in his memoir Experience, could be warm, even comradely. Powell devotes the lion's share of his book to Kingsley, which gives the Amis & Son an uneven feel. (Of course, the elder Amis lived to a ripe old age, so there's more to say.) Powell admires Kingsley up to a point. He finds a good deal of Amis senior's work uneven, and, in some cases, just plain wretched. I've often thought that Kingsley Amis wrote nothing as good as Lucky Jim, and Powell has done little to change my mind. If he admires the early romantic comedy Take A Girl Like You (1960), Powell's appreciations feel forced, as if he's had to talk himself into it. He enjoys Lucky Jim, but he feels a "lurking sense of an evasive hollow at its heart." Kinsgley's early novels, with their professional and academic settings, are "constrictingly middle class in their range."

Other times, Powell completely loses it. Trashing Kingsley for writing about Ian Fleming, he lambasts Amis for "his frightened denial of the complexities of good and evil, his avoidance of novels which he feared might be too difficult for him (his reluctance to read James Faulkner, for instance) and his lifelong recourse to easy escapism or popular cultural forms and their uncomplicated villains." This is a pretty strenuous indictment, and not altogether fair. Before the rise of academic cultural studies, Kingsley found value in popular entertainments, a point that seems to evades Powell altogether.

But Powell musters some appreciation for Kinsgley's place in the mainstream of English comic writing, and the solidity of his fiction: "people have pasts, and families, and futures; they know who lives next door, across the street, who's to be found in the pub and the corner shop. It's a very British scale of things, one which Kingsley would cherish and admire all his life…" Without getting too Freudian, Powell argues that Martin rejected such qualities. Indeed, the younger Amis always looked across the sea to America for his stylistic cues. In his own way, Martin Amis has always been an émigré. He loved the bigness and unruliness of his American masters. He was—and remains—a superb critic of Bellow, Philip Roth, Norman Mailer, and John Updike.

Not that Powell gives him much credit. Picking on Martin is old hat for the British literary classes, but Powell goes after Amis with vigour. Powell gives early Amis (The Rachel Papers, his debut, and 1978's Success) a passing grade. The Amis of Money (1981) and London Fields (1989) and beyond is a different story. Powell finds himself increasingly exasperated by Martin's ambitions. He accuses the younger Amis, with his imported techniques and his seeming contempt for realism, of writing a kind of gibberish. Amis's cleverness conceals an emptiness, Powell contends: "his fictional worlds, even at their most ambitious, seem insubstantial: typically, they rely on ingenious conceits to disguise their lack of foundations and, like conjuring tricks, they work wonderfully until quite suddenly they don't."

There are other problems. John Self, the debauched narrator of Money, remarks, "I'm not allergic to the 20th century. I'm addicted to the 20th century." You might say the same thing about Martin. He has taken it upon himself to probe the inhuman forces of the last century and of our own time; in the last few years, he has become a pundit of the September 11 era. More often than not, this can leave him sounding like a gasbag.

And, perhaps because of this preoccupation with inhumanity, there are few recognisably human characters in Amis's fiction. John Self and Keith Talent, the hooligan thief of London Fields, are ferocious creations, but they exist on one level. Dickens, a writer Amis is sometimes compared to, does a good bad guy; but he also has a tender side that seems missing in Amis. Martin Amis knows what can kill us, but little about what makes us live.

Matthew Price's writing has been published in Bookforum, the Los Angeles Times, The Boston Globe, and the Financial Times.