Novels are born in different ways. Some lucky writers have eureka moments and magic-up original concepts and bold outlines. Others are forced to sift and sort hazy thoughts and germs of ideas, shaping them over time into something resembling a narrative. For author Layla Al Ammar, the issues that form the background to her second novel had been incubating in her mind for years, but only as hard facts.

“These were issues that I’d been deeply absorbed in from early 2011,” she says, “and I had followed their developments closely – from the Arab uprisings across the region, the civil war in Syria, the refugee crisis, and the rise of the alt-right and nationalist rhetoric around the world. I had done all of this without consciously thinking that I would put it into a novel.”

She eventually found a way to channel fact into fiction. “Early in the summer of 2017, I felt compelled by the voice of my protagonist, and her experiences and character came to me.”

Later that summer, fate intervened and provided Al Ammar with a first-hand source. While on a visit to London, she was introduced by a friend to an acquaintance, Faraj Alnasser. "We ended up spending the day on Hampstead Heath where Faraj, who it transpired was a refugee from Aleppo, told us about his journey to the UK, as well as his experiences back home.

“It was serendipitous to say the least, and he was very excited to hear that I was drafting this novel at the time,” says Al Ammar.

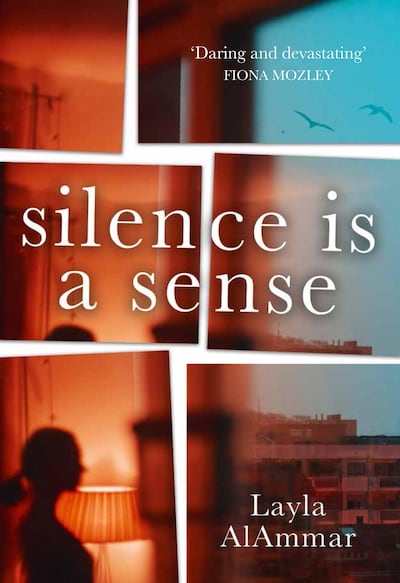

That book became Silence is a Sense. A captivating tale, it tells the story of an unnamed woman who has fled war-torn Aleppo for a city in the middle of England. Rendered mute from her harrowing ordeals, she turns her memories of what she has endured into articles for a magazine, publishing under the nom de plume of The Voiceless. When her editor asks her to rein in her opinions she yearns to answer back; when racial tension in the community escalates and she witnesses violence, she finds the ability to speak out.

Al Ammar impresses on many levels. Her protagonist – a scarred, troubled yet unbroken survivor – is a hugely sympathetic creation. Struggles past and present are expertly depicted, in particular a devastating account of a journey across Europe in a lorry. In addition, there are powerful snapshots of a country in turmoil: “The silence has cracked, and Syria, now, is all noise. Every death and every blast blots out more of the sun, blinding the world with distorted images and blackness.”

There is a moment in the novel when the narrator imagines herself as a published author. “It’s a dream from childhood,” she says, “one I gave up on almost before realising I had it.”

Al Ammar, who was born in Kuwait to an American mother and a Kuwaiti father, wrote throughout her childhood, but only started to take it seriously when she was in her late teens.

“It was at that point that I reoriented my thinking when it came to the writing process and started setting goals for myself.”

In her mid-twenties she left her job at an investment company in Kuwait and embarked on a creative writing course at the University of Edinburgh. It immersed her in a literary environment, surrounded by other readers and writers – which, she says, "is something I lacked growing up in Kuwait".

A couple of years after graduating, Al Ammar secured a publisher for her Kuwait-set debut, The Pact We Made. That novel also centred upon a young woman plagued by past horrors, in this case childhood abuse at the hands of a male relative. Al Ammar says that trauma is foundational to both her creative work and her current scholarly studies.

“I’m pursuing a PhD looking at Arab women’s fiction through the lens of literary trauma theory,” she explains. “I’ve always been interested in the psychology of trauma and recovery. How we process trauma. How we speak of it. How we represent it in art and literature. I’m interested in the function of such representations, the transmission of traumatic memory across generations, as well as how it manifests itself on an individual and a collective level, and with personal and political intersections.

"All of these interests inform my work in one way or another. The Pact We Made explores personal trauma and, in particular, the unacknowledged nature of it in societies like ours, which are shackled by notions of shame, and which result in a range of detrimental effects, especially for women.

"Silence is a Sense has a broader scope, dealing with personal and political trauma in addition to a sense of collective grief in the wake of failed revolutions and disillusionment," she continues. "The overlapping nature of these traumas produces devastating effects on the protagonist, which she struggles to process and work through."

In each novel, the female protagonist tries in vain to be heard. “This is an issue we always need to contend with, both in our fiction and just by virtue of being Arab women writers,” says Al Ammar. “There is a long history of silencing women, literally and figuratively, not only in our region and cultures, but around the world. It’s not surprising then that, thus far, my protagonists have been women trying to speak of their experiences in their own way and on their own terms.”

Al Ammar is keen to stress that the UK is not unique in terms of how it treats its migrant communities. “This is a global problem,” she says, “where migrants, refugees, and asylum seekers are dehumanised and compelled to prove their worth or add value to the host society.”

With two fine novels now under her belt, it will be interesting to see how Al Ammar proceeds from here. Does she plan to prioritise fiction-writing or will she relegate it to a side project while pursuing an academic career?

"I hope I'll be able to do both," she says. "I do plan to teach when I finish, hopefully both literature and creative writing since I enjoy working with young and aspiring writers. At the same time, I'd like to keep writing fiction, whether novels or short stories."