Ian McEwan's latest novel takes place in London during the 1980s, only this is not the decade as we know it. Britain has lost the Falklands War and prime minister Margaret Thatcher fights for political power against a rampantly popular left that is represented most conspicuously by radical socialist MP Tony Benn. Digital communication, recreation and commerce are so well established they have become a kind of chore. Voice-recognition software is commonplace. The nation's trains – still crowded and dirty – travel at about 400kph. Fridges come equipped with a sense of smell. Alan Turing, who in real life died in 1954, has achieved a breakthrough in artificial intelligence that is so seismic it becomes possible to produce synthetic humans with unsettlingly lifelike capabilities, characteristics and feelings.

Also in this world (in which "the future kept arriving") is Charlie, an online trader and artificial-intelligence enthusiast, who at the age of 32, has suffered a series of financial and professional failures. Passing most of his life "in a state of mood-neutrality", he regards himself as a figure who is "not bold, not withdrawn. Simply here, neither content nor morose".

Yet this apparently invulnerable equanimity soon finds itself under moral, amatory and existential pressure.

The causes of this come in two forms: on the one hand there is Miranda (the book features several references to The Tempest), a doctoral student of social history, who in addition to being a beautiful woman and, at age 22 and "mature for her years", is in the fortunate position of being Charlie's upstairs neighbour.

On the other hand there is Adam, one of two dozen cutting-edge androids – among the first batch ever made, hence the name Adam – that are available to the public for purchase.

Charlie is one of the few people who can afford to buy one of the androids, thanks to an inheritance bequeathed to him by his mother.

After Adam is delivered to him, Charlie hopes to find himself living with a ready-made friend. Instead, he winds up in the more complicated situation of having to shape Adam's character and find him a companion. With the help of Miranda, with whom Charlie is now in a relationship, he sets about programming the android with a personality to match his exquisite looks. Adam rapidly becomes the kind of being with whom Charlie had hoped to find himself entwined, a "companion, intellectual sparring partner, friend and factotum".

In return, Adam furnishes Charlie with a windfall on the stock exchange, performs all manner of practical tasks around the house and proves himself to be a dab-hand in the kitchen, with chicken tarragon a particular speciality of the android.

Soon enough, a sort of love triangle ensues, which starts out pleasantly enough before taking a turn when Adam – who by now is able to override his off switch – alerts Charlie to a dark moment from Miranda's past for which Adam believes she should be jailed. This all comes to light while the couple are preparing to adopt a child.

Jealousy, uncertainty and a restless examination of the nature of artificial intelligence, and the ways in which it might disrupt or reaffirm the nature of human moral responsibility, drive and animate the story. The reader is left to ask whether the ingenuity that brought Adam into the world was a blessing or a curse. Would it come to be viewed as "the triumph of humanism – or its angel of death"?

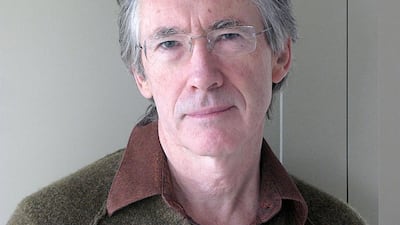

McEwan writes around these questions with sharpness, pace and vibrant curiosity. For all the intelligence of his exploration, you also seldom feel as though you're being nudged towards a conclusion and this resistance to resolution lends McEwan's preoccupations an extra level of interest and urgency. The novel is addictive and entertaining, but also moving, pleasingly disturbing and downright funny. One of the most amusing scenes comes as Charlie questions the state of his relationship with Miranda.

But at the same time, there remains something unsatisfying about the work as a whole. McEwan's commitment to supplying Charlie with embarrassingly cliched thoughts, such as, "We had no choice but to follow our desires and hang the consequences," is exhausting. This inattentiveness is also replicated in the sense that not one of the characters in the book feel possessed of a fully resonant life.

It is as though, in a similar way to other McEwan works in the past, such as 2010 novel Solar, the subject of the story has been elevated above its aesthetics.

The result certainly yields numerous moments of pleasure, but that does not stop it from feeling artificial.