"A writer should carry coal in the morning and write in his spare time." That, says the Egyptian novelist Khaled Al Khamissi on his website, is broadly the attitude of the Arab world to "work" and "writing".

Books: The National Reads

Book reviews, festivals and all things literary

"But somehow," he writes, "I've bridged this great divide and here I am, working as a novelist. That is what I do."

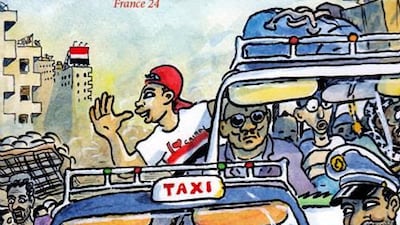

Cultural reservations about his profession notwithstanding, he shot to fame upon the 2007 publication of Taxi, a best-seller that has just been retranslated and republished by Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation Publishing with a post-revolution note by the author.

Taxi remains relevant - even more so - after Egypt's January 25 revolution and the fall of Hosni Mubarak. Its 58 narratives weave a story of despair, poverty and hopelessness through the voices of Cairo's taxi drivers. Although it could be held to reflect badly on the Mubarak administration, there was no political reaction.

"The government at that time wasn't interested in culture; they didn't think culture was a danger to them," he says, speaking from his home in Cairo. "They were afraid of audio-visual, radio, TV and cinema, but regarding books I think they said to themselves 'leave them to write whatever they want. It's not important, no one reads, even those who do are few'."

Al Khamissi was born in 1962 in Cairo. His mother died when he was five years old (and his sister six months) and when he was nine, his father fled Egypt for political reasons, so he was largely brought up by his grandparents. His father died in 1987.

"When I write I don't think about the consequences - writing is an act of freedom and if we lose our freedom in writing, we lose the writing ourselves. We cannot put barriers up in writing at all, because it will kill the writing," he says.

The novelist spent time working and studying with a family in Paris but, homesick for his native Egypt, he returned in 1989.

Taxi - first published in Arabic by Dar El Shorouk - was written from Al Khamissi's own experiences, but although the narratives came from what he had been hearing on the streets of Cairo all his life, he emphasises that it is a work of fiction and that no real person is specifically documented in the book.

The novel has since been translated into more than 10 languages, including Greek, Polish and Korean, but although it was a best-seller in Arabic, both native English speakers and native Arabic speakers told the author that the first English translation was difficult and that the book would benefit from being translated again; hence the new version released this year by Bloomsbury Qatar.

"The book is a little bit difficult to translate because part of it is in colloquial translation and we don't have a history of translating this," he says of the new version. "We have the old translation dealing with the classical Arabic language, but translation from colloquial Arabic is very new.

"It was difficult for the translator, as there was not the history behind him and it was something new."

Taxi serves as a microcosm of Egyptian society and its problems - from the driver working two jobs and studying for a master's degree to try to support a young family, to the driver who won't return home until he's made enough money to pay off a fine and falls asleep at the wheel because he's been driving continuously for three days. What's written is "exactly what the poor people on the streets of Cairo" were talking about at the time, he says.

"The streets were highly strung, social action was very high and the streets were motivated against what was happening. It's very representative of the streets of Cairo at that time."

Al Khamissi's second novel, Safinet Nouh (Noah's Ark), which was published in 2009, is written entirely in classical Arabic. Characters are united by their desire to leave their homeland, because of its lack of democracy, its "chaos" and all its social problems.

Things are not much better today, he says, but at least there is now a renewed sense of hope.

"The streets are totally unhappy and unsatisfied by what has happened up to now. They think we had a huge opportunity to step forward, but the army and the prime minister didn't use these opportunities wisely.

"The streets… are trying to speak about how to make a new -tomorrow."

The fall of the Mubarak regime has created hope among the people, Al Khamissi says, but it's a different kind of hope.

"When you have hopes and dreams for the first time in a really long time, these hopes and dreams have expectations. Now we talk about expectations, dreams, hopes and their relationship with reality as well as what we have to do next."

The transformation hasn't just been about a people gaining hopes and dreams, but altering the self-perception as well.

"We have become a people who feel that they have gone through a transformation from being a human being to a citizen - it's an enormous revolution in itself," the novelist says. "They didn't feel they were citizens before and now they feel like they're citizens… having the ability to act in political -issues."

Follow us on Twitter and keep up to date with the latest in arts and lifestyle news at twitter.com/LifeNationalUAE