Ever since humankind first daubed charcoal onto cave walls, or carved rocks into voluptuous shapes, it has tussled for a physical representation fit to reflect its dreams, fears and desires.

In other words, man has long sought out a way to express the inexpressible in the most direct way possible.

The folk totem has been, in part, a key point in this journey. Totems have played a vital role in spiritual life - objects associated with ritual and belief that, in some cases, are thought to contain their own potent spiritual power in themselves.

"What interests me about folk art is that you can have a very complex idea - something like the idea of transcendence or death - and are able to pare that down to one solid symbol," says Fahd Burki, who presents a line-up of his own totemic forms at Grey Noise this month. "These symbols can reach a point at which it starts to look naive yet are also simultaneously very direct."

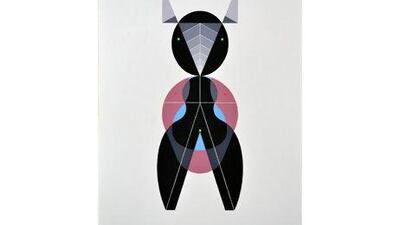

Burki's forms, as he notes, have a certain ominous quality to them. In deep black acrylic on paper (all hand-painted, despite their graphics-like clarity) and interspersed with block spectra of colour and unfeeling eyes, the Pakistani artist has crafted a series of symbolic forms that are both familiar yet entirely foreign.

Each is vaguely humanoid in shape, with an inherently bare-bones aesthetic that makes them appear a little monstrous. In an untitled piece, for instance, a figure stares back at us with toxic-green pinhole eyes but has a loose suggestion of some maternal quality in its shape. In another, we see a billowy figure encapsulating a foetal shape rendered in a rainbow of colours.

"This particular image, for me, represents an internal energy, but I think it really depends on what the viewer gets from the image," says Burki.

The development of these pieces arose from the artist exploring various totemic traditions, notably those found in indigenous North American cultures and also images relating to Shinto beliefs in Japan. "Shinto ascribes a spirit to almost everything inanimate, from trees to houses," the artist explains. "A lot of Japan's contemporary monster culture in the wake of the Second World War, such as Godzilla, came out of this folklore, which is called the Yokai.

"Woodblock printmakers like Katsushika Hokusai gave shape to the forms that we now call Shinto spirits. In contrast to what I do, these images are extremely detailed but at the same time are two-dimensional. For me, that connects them to the tradition of miniature painting found in the subcontinent: absolutely flat images that lack perspective."

This connection with miniature painting is especially poignant in the context of Burki's own imagined totems. He notes that contemporary miniature painting has lost the narrative quality that it was first intended to have. No longer do we read or require these images as self-contained stories, detailing life in the great courts of Persia and the Mughal Empire.

Instead, he says, the idea of miniatures has simply become two-dimensional paintings. The totems that he pored over in researching this series of paintings are also somehow lost to our perception. Like unfathomable hieroglyphs, we're no longer able to plumb the myriad depths that folk art objects and symbols once held for their respective communities.

His own totems and their own quizzical, unfathomable nature are an ironic play on this loss of sensitivity. "It's trying to imitate folk art in a technological world where you've explained everything through science," he says.

Until February 28 at Grey Noise, Alserkal Avenue, Al Quoz, Dubai